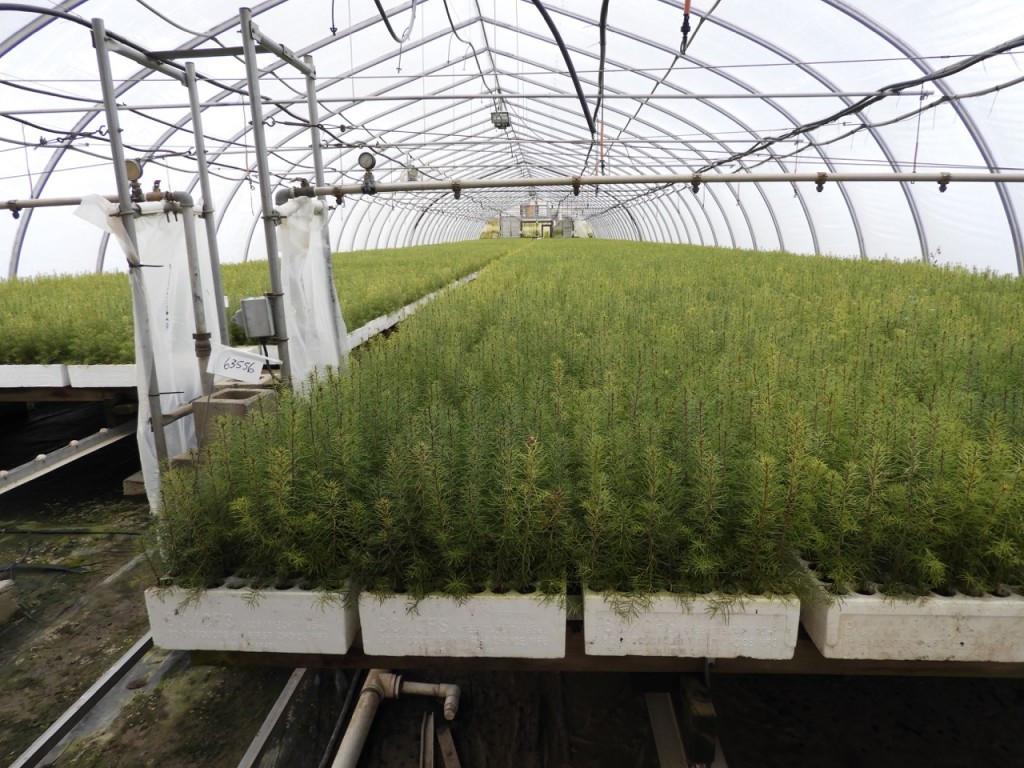

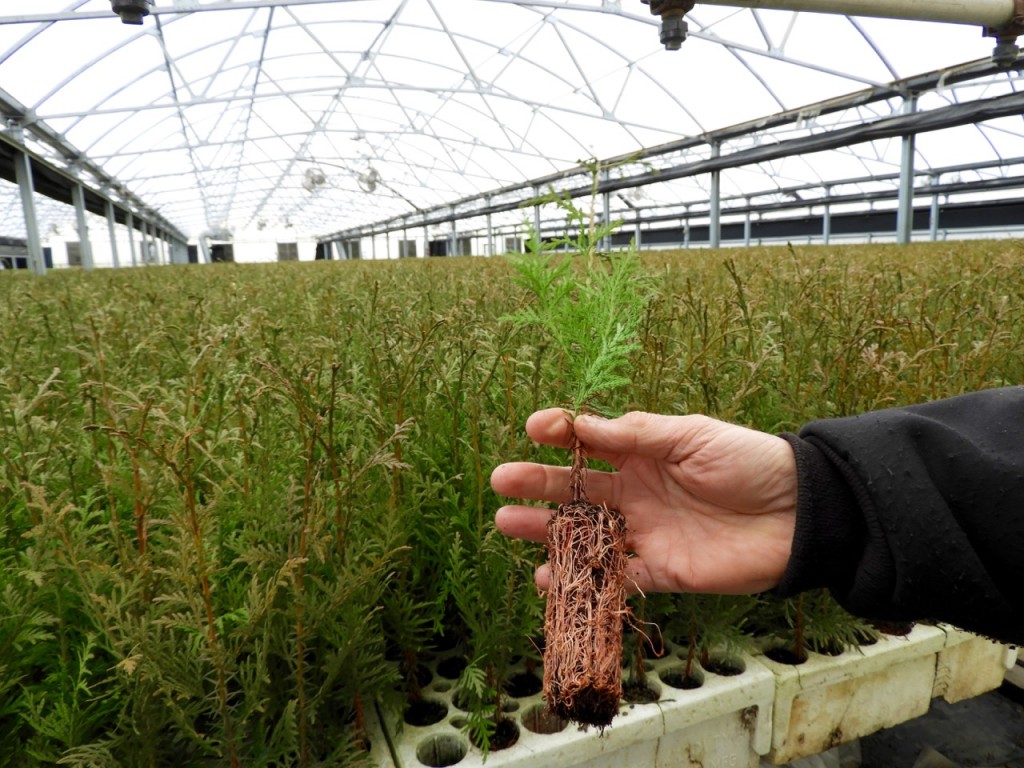

One of a million cedar tree seedlings in this Sorrento greenhouse grown in plugs, photo by Jim Cooperman

One of a million cedar tree seedlings in this Sorrento greenhouse grown in plugs, photo by Jim Cooperman

While the two facilities in the Shuswap that produce seeds and the three that produce tree seedlings for re-stocking forestlands only represent a small percentage of the local economy, they do play a major role in supporting the provincial forest industry. Government regulations stipulate that all logged cutblocks and much of the forestland burned in wildfires must be planted with seedlings produced from tree stock that is best suited to the site, thus there is an ever-increasing demand for seeds and seedlings.

Called ramets, these trees are clones grafted to root stock to produce superior seeds for the forest industry

The forest service created the Skimikin tree nursery in 1973, and two years later Maarten Albricht was appointed to set up a seed orchard at the site. After moving to Tappen from Victoria where he worked in the ministry’s inventory division, Maarten’s first task was to obtain the best spruce tree stock possible. In mid-winter the tops of the selected trees were shot off and branches grafted on to 3-year old seedlings and first grown in greenhouses, until planted in the orchards in 1979. It took 15 years before these clones or ramets produced seeds for planting.

Staff need to water , mow the lawn and tend these ramets at the seed orchard

Staff need to water , mow the lawn and tend these ramets at the seed orchard

There are now four tree species grown on 13 orchards in the 79-hectare property, including spruce, white pine, lodgepole pine and Ponderosa pine. As well, there are research trials, a yellow cedar hedge that produces cuttings and an experimental plot of coastal red cedar that is being tested for reproduction performance in the interior. The full-time staff of two and seven auxiliary staff look after the planting, irrigation, weeding, pruning, disease prevention, pollinating, storage and cone collection, for which 10-60 cone pickers are employed depending on annual production.

The cones are stored in sheds before they are shipped off to Surrey

The seed orchard is part of the provincial tree improvement program managed by the Forest Genetics Council of British Columbia with a goal to increase the volume and value of future forests. There are 18 staff from the Kalamalka Research Station near Vernon who also utilize the Skimikin orchard for breeding and progeny testing to produce trees with improved growth and yield, better branch formation and disease resistance.

Bags cover the pollen flowers to insure the right pollen is used to pollinate the selected ramets

Bags cover the pollen flowers to insure the right pollen is used to pollinate the selected ramets

All the cones produced in Skimikin and all other orchards are shipped to the Tree Seed Centre in Surrey, where the seeds are extracted, stored, tested, certified, and shipped to tree nurseries all over the province. Skimikin seeds are used to grow trees in the Bulkley Valley, Peace River, Kootenay and Quesnel regions and younger orchards will produce seeds for the Thompson Okanagan, Nelson and Prince George areas.

These seedlings will be lifted soon for storage prior to spring planting

When the forest service sold off all the provincial tree nurseries in 1988, it also tried to sell the seed orchards, but without success. PRT eventually purchased the Skimikin nursery, which is now one of fifteen operated by the company including one in Armstrong. This year Skimikin produced 15-million container seedlings for spring, summer and fall plantings and have a goal of 17-million for 2019. Forest companies purchase the seeds they need from Surrey and contract the nursery to grow them.

In November the tree seedlings are lifted out of the Styrofoam blocks and packed into boxes for cold storage

In November the tree seedlings are lifted out of the Styrofoam blocks and packed into boxes for cold storage

The nursery’s nine full time staff look after the planting, growing, thinning, watering, packing and storage of the spruce, fir, lodgepole, white pine, cedar and hemlock seedlings.

The seedling are kept in cold storage until they are shipped out in April for spring planting

Upwards of 45 part-time staff are brought in for the thinning operation and the lifting of the seedlings out of the Styrofoam containers into boxes that are kept in cold storage rooms. The nursery’s greenhouses are lit up and heated during the winter to force the seedlings to continue growing.

A few of the 65 greenhouses at the Sorrento Nursery

In 1988, two South Shuswap families, the Barnards and Hamiltons, started the Sorrento Tree Nursery and two lodgepole pine seed orchards on 150 acres on a bench above the highway. Today, the successful business employs 15 full-time and 25 seasonal staff to produce seeds for the Bulkley Valley and the Central Plateau regions of the province, as well as 16-million Douglas fir, spruce, lodgepole and cedar seedlings.

Sorrento also had a seed orchard

Sorrento also had a seed orchard

With the area of forest lost to wildfires increasing and the push to plant more trees to combat climate change, there is a shortage of greenhouses in the province. The Shuswap’s newest operation, Mt. Ida Nursery, will help fill the growing gap as it ramps up to produce millions more, much needed fir, pine, larch, cedar and spruce seedlings at its facility near the Salmon Arm airport.

These seedling arrive in blocks ready to be lifted for cold storage at PRT

There is some irony surrounding the success of tree nurseries, as the need for seedlings is increasing because climate change is burning up forests faster than they are being replaced and clearcut logging diminishes natural regeneration. As well, as the climate changes, growing conditions change and trees are moving north. Given that one-day the Shuswap will be more like Northern California, there is definitely a need for more research.

POSTSCRIPT

The process to improve tree stocks is complex and time-consuming, but the results have been promising with from 3 to 30 percent increases in growth rates. Cones are collected from exceptional trees growing in plantations and these seeds are planted and then observed as they grow. The best ones are selected with clippings taken for grafting on to other stock. In the orchards, pollen is then taken from selected trees to be used for creating the seed cones.

These ramets in this Skimikin seed orchard are being replaced with new, improved stock

All of this work can take decades before new improved stock for cone production is available. One of the early seed orchards has been removed at Skimikin and is being replaced with new, improved ramets that come from trees with faster growth rates and better formation.

A sea of seedling in this PRT greenhouse

A sea of seedling in this PRT greenhouse

Seed orchards are developed for different zones in the province, to ensure that the trees are best suited for the climatic and ecological conditions of the area. However, research is now underway to determine how climate change will require revisions to how the zones are determined. Trees once suited for growing in southern zones may end up better suited for growing farther north.

The process to produce seedlings at the tree nurseries begins with forest companies ordering the seed. There are two classes of seeds, Class A comes from seed orchards and Class B comes from wild trees. Approximately 75 percent of the seedlings are grown with Class A seeds and Class B seeds are only used when there is a shortage of the improved seed.

The seeds are sown with a machine from January to May, depending upon when the seedlings are needed. The goal is to plant an average of 1.6 seeds in each hole. Three weeks after planting, the blocks are thinned, and a “dipple” wire is used to pull out any extra seedling and replant these in holes without seedlings. The seedlings begin growing in heated greenhouses under lights and then are moved outside in the late spring.

Sorrento Nursery owner Harry Hamilton reports that despite their 65 greenhouses, they cannot meet the demand, given the ever-increasing amount of once forested land requiring planting due to logging and wildfires. Growing seedlings and maintaining a seed orchard requires a large volume of water, which the Sorrento Nursery obtains from the lake via 3 and 4 inch pipes connected to pumps at the lake and to booster pumps halfway up the pipeline.

The goal of forestry is ultimately financial profit and clearcutting produces the greatest financial return, yet it results in the greatest amount of ecological damage. Natural forests are mowed down and replaced with seedlings designed to grow faster than natural trees. Often, the blocks require brushing, thinning and herbicide treatments to discourage competition and speed growth, even though the natural growth of deciduous trees and brush is best for the long term health of the forest. Technically, reforestation is a misnomer, as planting tree seedlings in cutblocks results in plantations that will be cut down again in approximately 80 years.

The business of growing seedlings, while good for corporate profits, is integral to industrial forestry, which will likely result in serious long-term negative consequences, including the loss of many forest dependent species, steep reductions in available wood supplies (falldown) and impacts to water quality, quantity and timing of flow.