in present day Michigan from a legendary 1675 event

[Note: The following article includes quotes with language that should never be used today as it would be most disrespectful of First Nations. The word savage comes from the French word sauvage, which means wild and in this context wild people. It is unlikely that Nobili and other missionaries used this word to convey the other meaning – violent and frightening. ]

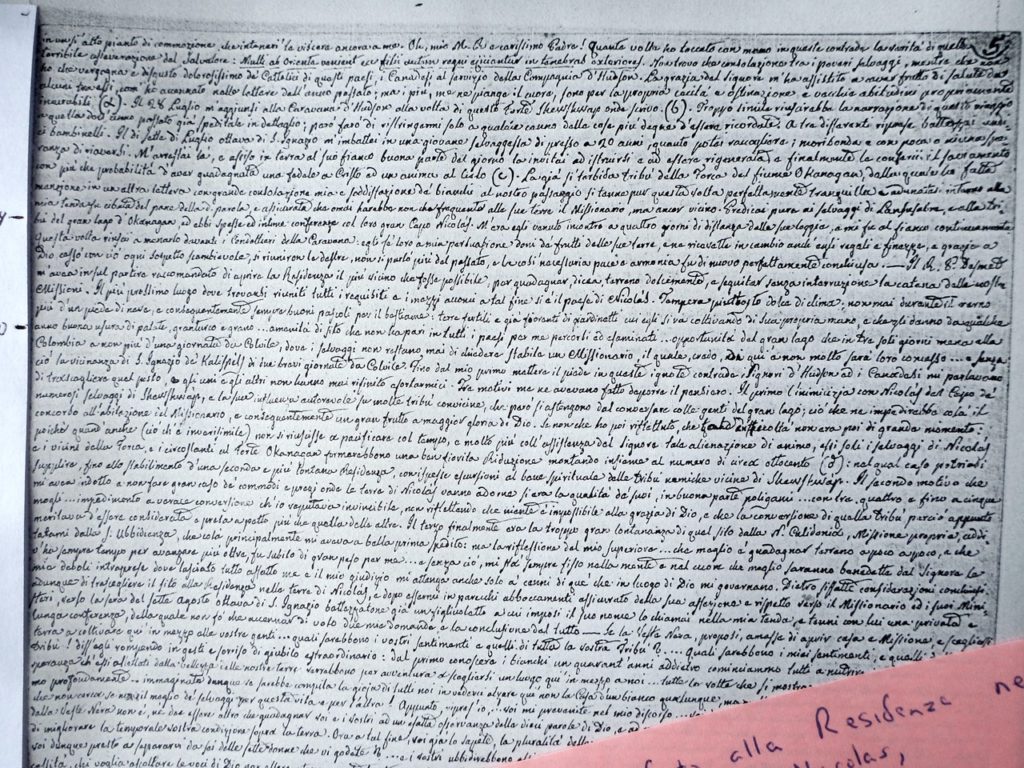

By happenstance, 237 pages of letters written by Italian born Jesuit priest, Father Giovanni Nobili from 1845 to 1847 arrived by email from a friend and author in Williams Lake. These documents, which have yet to be read by most historians in the province, had been in the Vatican vaults until the Tsilhqot’in First Nation was able to acquire them several years ago for the Xeni Gwet’in lands claim court case. Their legal team, Woodward and Company, translated the letters from Italian, Latin and French into English.

Father Nobili (1812-1856) was the second missionary to arrive in the province’s interior. His objective was to continue the work of his predecessor, Quebec born Father Modeste Demers. He landed in Fort Vancouver at the mouth of the Columbia River in late 1844, where he ministered the Hudson’s Bay employees and learned some Indigenous dialects. In June 1845 he headed east to Fort Wallawalla, Washington and from there he joined a small fur brigade heading north into New Caledonia (the first name assigned to British Columbia, although used by Nobili to describe the region north of the Shuswap).

Nobili’s initial destination was Fort Alexandria on the Fraser River halfway between Williams Lake and Quesnel. The trip began with a life-threatening adventure that included becoming separated from the group, running out of water in the desert, avoiding rattlesnakes, dodging a bullet, and riding through lava fields and over mountain passes. He eventually made it there, rather shaken but unscathed.

To find relevant sections of the letters, it is necessary to wade through reams of religious doctrine, as Nobili’s goal was to do God’s will by saving the Indigenous people (or “savages” as the missionaries called them) from the devil. He was called a “black robe” and was surprisingly well received by all the tribes. He wrote, “There is not a single nation or tribe that does not love me greatly and ask to receive religious instruction: to a higher or lesser degree, there is hope of good fruits for each one on them, if a minister of the Lord is there to sow the seeds of the divine word.”

Nobili explained how the Indigenous population had been much higher, but it had been drastically reduced due to diseases. He interpreted this loss as due to “God’s justice, preordained for the just punishment of these sensual peoples seems to have arrived.” Adding to their woes, the tribes were suffering greatly from famine in 1845 due to a collapse in the salmon fishery. His solution was to establish “Reductions,” the term used for Christian settlements, such as the ones the Jesuits created in South America.

Here he writes about the west Shuswap (called then the Upper Lake), where he visited in 1846. He thought it would be ideal for a settlement: As far as the land is concerned, there is good land in several areas, and, since the climate is milder, it’s suitable for growing potatoes just about anywhere, and in some places, it could grow barley, wheat, and the like; however, there is only one location where the conditions described earlier can be found. This place lies one day’s journey East of Fort Shoushwap, along the shores of the lake from which the clear and extremely calm waters of the Thompson River issue; in season, the salmon run up both. The soil is excellent and the place is pleasant. An extraordinary thing, in addition to pines, there are cedars. The savages have been planting potatoes here for some years, they are so good and so abundant, the savages use them as a staple to trade with all the neighbouring tribes, and even with the whites and the Lord of the Fort. The Fort is accessible by land and by water. Three-hundred and twenty-two savages live there permanently. They are called the savages of Upper Lake. In a few days, after having instructed them for over one month and a half, I will baptize their Great Chief and his wife. Both he and his savages are extremely attached to their minister of God and greedy for the divine words.

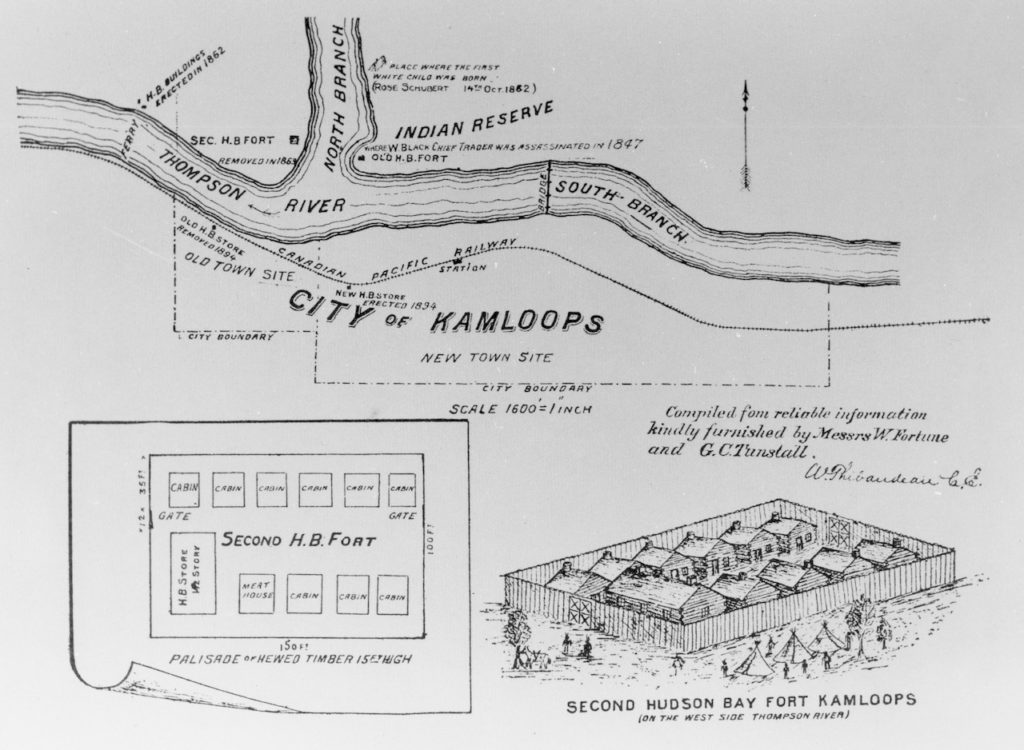

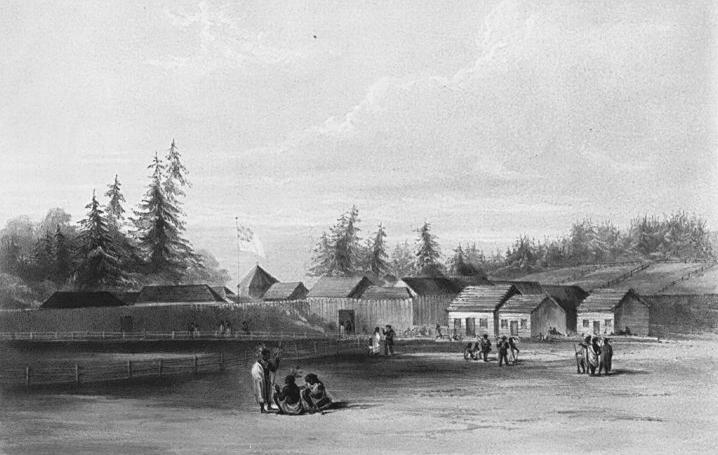

Diagram of second HBC fort and its locations, circa 1900. Image courtesy of the Kamloops Museum and Archives.

The “Great Chief” he referred to was Silhowtken (the name Mary Balf used in her history of Kamloops), who after his baptism, received the name Adam. Nobili referred to the Hudson’s Bay Thompson River Post as the “Shoushwap Fort” and its chief factor as the “Lord” of the fort. He also used on occasion the word Atnass for the “Shoushwap” and the Okanagan, which was the Carrier name for tribes other than their own. Throughout his travels, he was accompanied by a guide, a novice who assisted with the services and an interpreter, who sometimes needed their own interpreter. Given the language barrier, Nobili’s words often had different meanings that what were intended for the sometimes hundreds of Indigenous people who gathered to hear him. While the missionaries may have thought they were converting pagans to Christians, the Indigenous people often interpreted the prayers and practices in terms of their own spiritual beliefs.

Nobili most often described the “Shoushwap” in complimentary terms, but he had a far different impression for other nations. He often described Indigenous people as lazy, poor, and sinful, and complained about their sensual vices, especially gambling and polygamy, which they had to renounce to be baptized. In one entry, he spoke of a concern that Chief Nicolás “had threatened to attack Fort Shoushwap and to exterminate the whites.” Consequently, he hurried there from Fort Alexandria in the middle of the winter, to thwart the violence. The chief told him the plans were untrue and then “burst out in angry diatribes and complaints against the Shoushwap savages…”

Throughout the letters, there are occasional hints that some of the evils he associated with the Indigenous people were in fact due in part from their association with the fur traders. “The Indians of the Forts are lazier and more frivolous than the others, this is so because they are, so to speak, “better off,” and because of their continuous association with the Hudson’s Company servants, they [the servants] are a thoroughly corrupted lot having come here from Canada in the pursuit of all kinds of licentiousness.” At one point, he remarked, “…the mind of the savages is naturally no less open that that of civilized nations, and that therefore not only it could be cultivated, but perhaps even reach perfection.”

Even though Nobili complained about how Hudson’s Bay employees corrupted the Indigenous people, when compared with the situation south of the border, these employees were princes. In one passage, he explained why Indigenous people appreciated the fur traders, Generally they are fond of the Members of the Hudson’s Company because they know the advantages and help that they derive from them. And the truth must be said, while the Americans in New California, around Wallamette, and in the whole of the Oregon appear to give as their primary aim the extermination of the poor savages (and this Most Reverent Father is neither a calumny nor an exaggeration), by the same token the Members of the Hudson’s Company do their utmost to keep the savages alive, and of this I have had convincing evidence during my travels and visits to several Forts. It is a fact that they are interested in them in order to make the fur trade last as long as possible, but this does not diminish the merit of many Lords, who, nevertheless, act most charitably towards Indian individuals and tribes from who they have absolutely no expectations of profit.

Throughout the nearly three years that Nobili spent in New Caledonia, he travelled often on horseback between the Okanagan and as far north as Fort St. James and Fort Kilmaurs on Babine Lake for his missionary efforts. In addition to his proselytizing efforts that included erecting giant log crosses, he had many adventures and close calls. One time, his “Canot” (a small boat, likely a canoe) almost capsized when they were crossing the frigid Fraser River with their horses swimming behind them. Often, they had to cross rivers and canyons over logs, where one misstep could have been fatal. As a result of his exposure to harsh weather and being forced to survive on meagre rations, his health went downhill.

Despite having secured land from Chief Nicolás at the head of Okanagan Lake, where a home and Mission were under construction, his superiors decided that he must return to Fort Colville as the Jesuits had decided to leave New Caledonia and focus on their work in California. Nobili then travelled to San Francisco, where he received medical attention and served as an assistant pastor. He founded a Jesuit College in Santa Clara that later became a university. There, while supervising construction, he stepped on a nail and contracted tetanus, then died at the age of 44 in 1856.

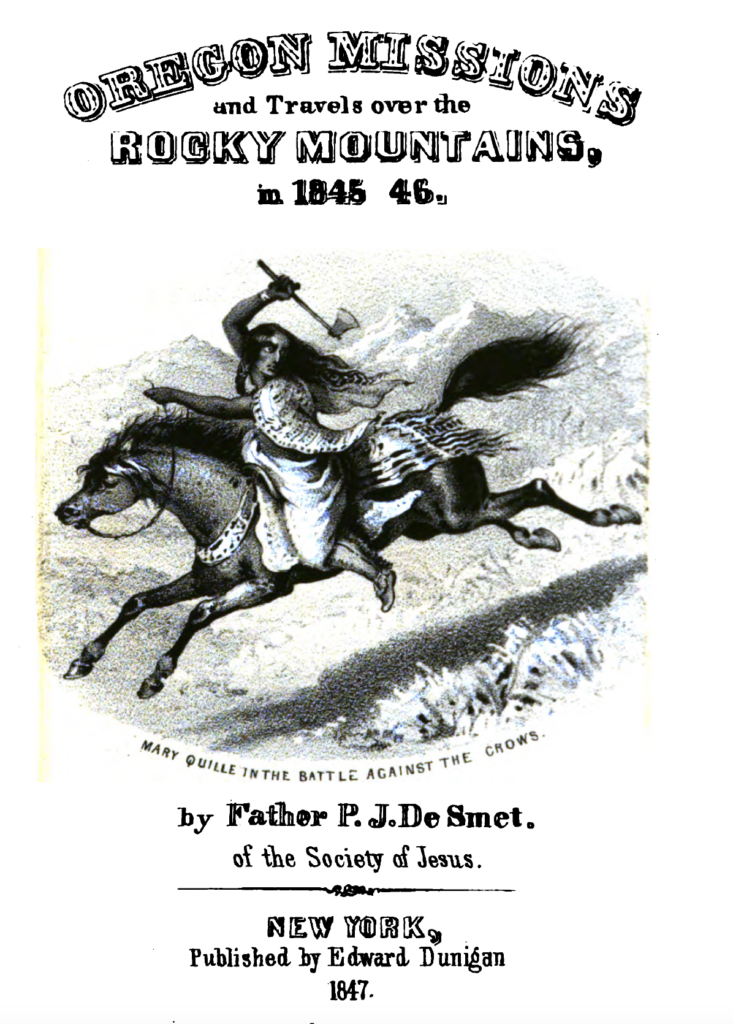

While undertaking further research on the life of Father Nobili, I was led to an 1847 publication by his colleague Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, entitled Missions and Travels over the Rocky Mountains in 1845, 46. It includes an extract from another Nobili letter that concerns his time with the Sioushwaps (he used a different spelling) in the summer of 1846. Nobili wrote that on July 27th, he had baptized nine of the chief’s children. Later while on the road, he wrote how “three old men came to me and, earnestly begged me to take pi’y of them, and prepare them for heaven!” He administered to them, as well as to 46 children.

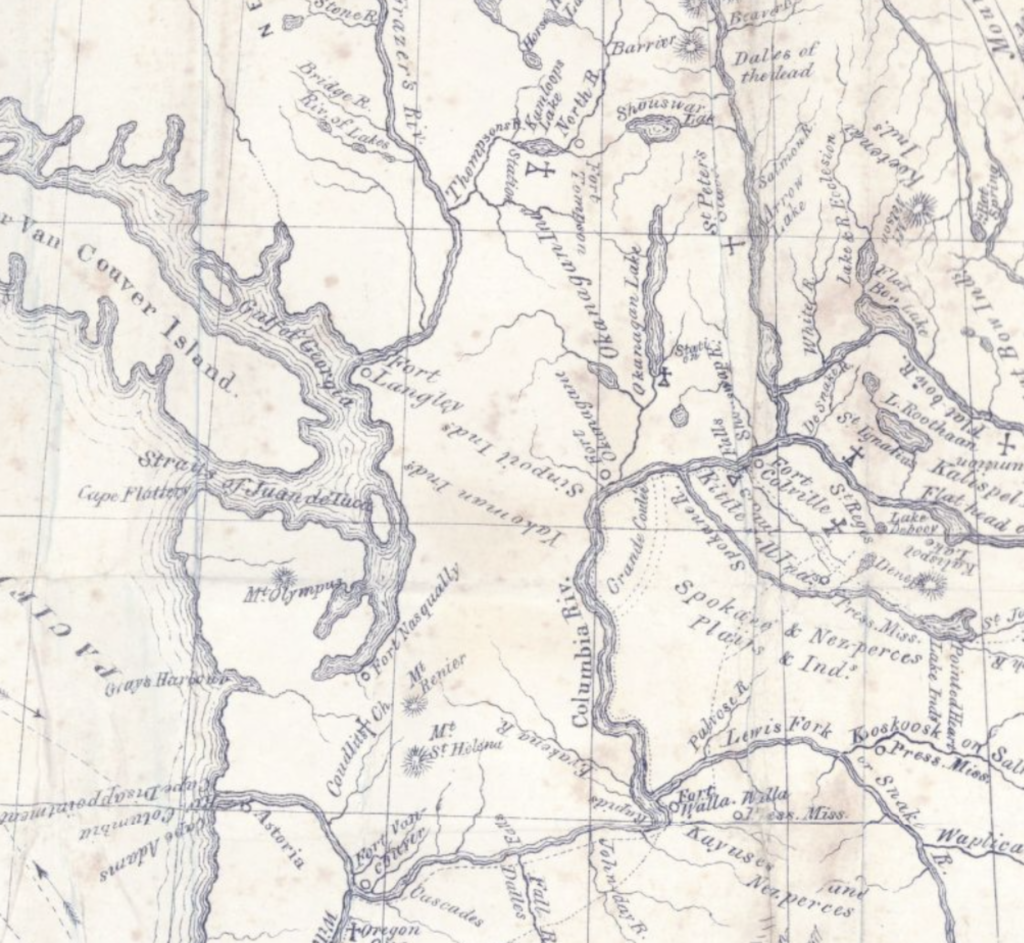

Note the shape of “Shouswap Lake” and the location of Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River

Then on August 11th, Nobili wrote: …a tribe of Indians, residing about the Upper Lake on Thompson’s River, came to meet me. They exhibited towards me all the marks of sincere and filial attachment. They followed me several days to hear my instructions, and only departed after exacted a promise that I would return in the course of the following autumn or winter and make know to them the glad tidings of salvation.

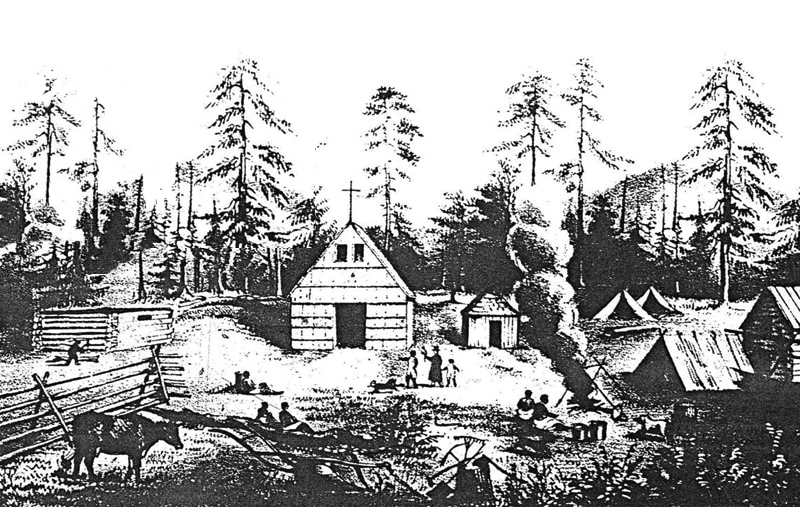

In the next paragraph of this letter in De Smot’s book, Nobili described how they built the first “church” in this region. At the Fort of the Sioushwaps, I received a visit from all the chiefs, who congratulated me on my happy arrival amongst them. They raised a great cabin to serve as a church, and as a place to teach them during my stay. I baptized twelve of their children. I was obliged, when the Salmon fishing commenced, to separate for some months from these dear Indians, and continue my route to New Caledonia.

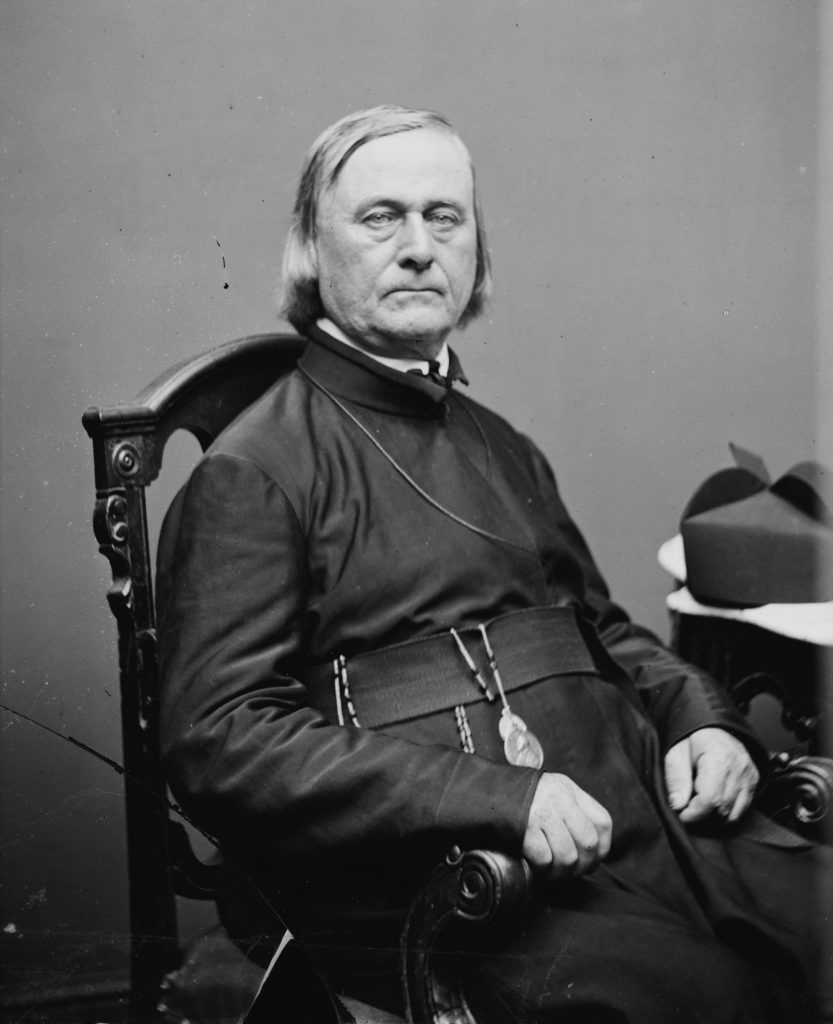

Father Pierre-Jean De Smet was born in Belgium and after just one year in a Seminary, he came to the U.S. in 1821 to become a missionary. After five years of study, he was ordained in 1827 and over the succeeding years, he studied Indigenous languages, learned map-making, and with other priests, founded a number of missions. He worked with many tribes, including the Cree, Blackfoot, Chippewa and Flathead. His explorations are legendary, including his adventures in Western Canada where he travelled through the Kootenays to the headwaters of the Columbia River, into the Rocky Mountains up to winter at Fort Edmonton and then to Jasper House on the Saskatchewan River. One of his most famous exploits was persuading Sitting Bull to accept the Treaty of Fort Laramie. Before he passed away in 1873 in St. Louis, De Smet wrote numerous books and collections of sketches and letters, including the one mentioned above.

We can only hypothesize why Indigenous people warmly embraced Christianity, as the Nobili letters and De Smet books suggest. Prior to the arrival of the missionaries, the First Nation peoples in Canada had decades of interactions with the fur traders and hence had learned much about European technology, such as iron implements, farming, blankets, guns, knives, and beads. Some had even learned to speak rudimentary English. Weakened by diseases and with their populations in decline, it is likely that many viewed the European religion as a path to salvation as they understood it, because it was part of a culture attached to the technology that they had quickly adopted.

Another view is that because most Indigenous people were very spiritual by nature, they connected their beliefs with those of the missionaries and thus could accept the Christian teachings as they interpreted them, especially the part about being kind to others. They may have seen the missionaries as a type of sign from their spirits. This theory is supported by some Tsiljqot’in elders who reported how they continue to blend Christianity with their own spiritual beliefs.

In his ethnographic notes from 1906 to 1910, James Teit wrote about the Indigenous attitudes towards the missionaries as he observed them. There was diversity of views, that ranged from acceptance of Christianity to avoidance, along with following the old ways. One group was pragmatic in the views and saw no contradictions between their stories and the Christian stories, so they decided to attend church, avoid evil ways and use the prayers in case the missionaries were right and if they were not, they thought they would be no worse off than others.

In more recent times, in a stark reversal from the early days of the missionaries, the goal for many First Nation peoples is to revive their traditions, as it is now obviously clear that Christianity, rather than benefiting their people, was an integral part of the European effort to destroy their culture and their once successful, egalitarian way of life.

POSTSCRIPT

Here Nobili described the brigades and what the forts were like:

But for these places to bear the name of Forts is really inappropriate since they are just trade posts consisting of a square palisade enclosure, a warehouse, a small, modest house (made of wood, of course) for the Bourgeois, or Commis, and another one for the staff, which in some places may number eight or ten men, but ordinarily numbers no more than three or four. Here one never sees any new faces, either American, or of any traveler at all, and least of Protestant Ministers, to whom, I believe, has never occurred, nor will it occur, I am sure, to embrace so much poverty and face so many discomforts and dangers to themselves in order to do good to others, and this heartens a Catholic Missionary, and is not an inconsiderable advantage of a mission [missionary work] in America. At the beginning of May the Brigade with its load of furs, moves from Caledonia towards Fort Vancouver: this [Brigade] consists of a body of men that keeps getting larger keeps getting larger until it reaches forty or so by the time it reaches Okanagan, it is led by two Members of the Hudson’s Company and it takes it at most a month and a half to make its way down partly on horseback, partly by water, if the [conditions of the] rivers are favourable. And at the end of June it makes its way up again with all the supplies that are necessary to trade furs.” Those who go to the northernmost Fort spend over three months in the journey; the others from two to three, except those who go to Fort Shoushwap, which can be reached in a month and a half.

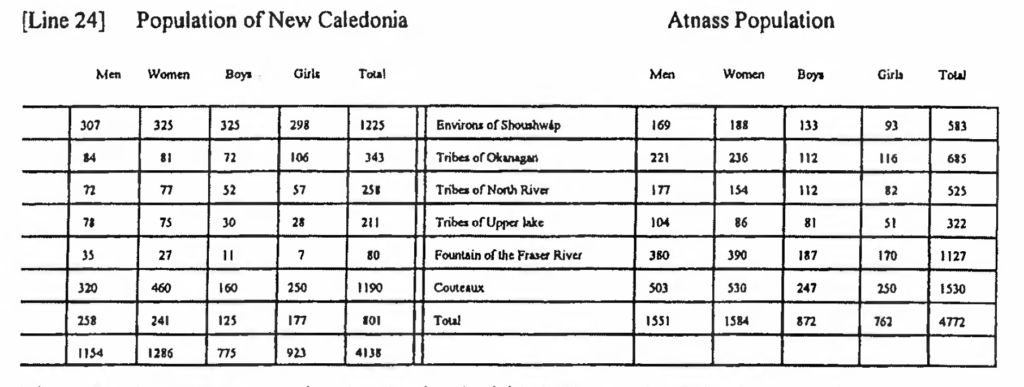

Throughout the letters, Nobili included population numbers that appeared to be exact, but were likely very rough estimates. He would not have been able to count all the Indigenous people living on the land far from the places he visited. Here he provided his total estimate for much of New Caledonia: From Okanagan to the southernmost boundary of New Caledonia can be found six nations and four very different languages, the language of the Okanagan, the one of the Shoushwap, the one of the Couteaux and the one of the Fountain of the Fraser; the nations that speak the second language [Shoushwap] go by the common name of Atnass. All of them together total four thousand seven hundred seventy-two.

Here Nobili added more population numbers and provides his interpretation of the leadership system: Each nation is divided into many tribes, but as far as I know, no tribe has more than two-hundred people, and each has one Chief, or two at the most. Chiefs bear this title with no special honour attached to it and with little authority of their subjects, except for the odd tribe. This derives from the fact that since these nations are no longer at war with one another, as they were some years ago, they lack the principal reason for submitting to the will of only one person.

Here is another one of his population estimates (unfortunately the names of the tribes are missing on the New Caledonia list):

Here Nobili wrote about his plans for Indigenous language dictionaries and his concern about the rising costs of goods: I am putting together two dictionaries of two languages: Shoushwap, and the one of the language of New Caledonia to facilitate the labour of anyone who may come here to replace or to help me. But French is indispensable, and English extremely useful. The Hudson’s Company will not oppose our plans, and its Members here will help us, l can vouch for that. Unsolicited by me, the above-praised Lord of this Fort spontaneously wrote His Governor General about the raise he ordered last year of the prices charged to us, since as you know, R[everend) F[ather], we now pay one hundred percent on our goods, and requested him to give us a discount of fifty percent, as before. He tells me that the sudden increase in prices came not out of ill feelings towards the Catholic Priests and their Missions, but was rather the result of the said Governor vying against McLaughlin. [McLaughlin was referred to as the ”Father of Oregon” and was the chief superintendent of the Hudson’s Bay Company from 1825 to 1845.]

In many of the letters, Nobili was most unkind to Father Demers, who made promises that he did not fulfil: Should the savages of Caledonia not see a Priest come back in the only manner possible at least for now, and that is with the Brigade, they might think that my visit of last year was just like the visit of the Canadian Priest Demers, who never showed up again, and earned for himself the label of liar. If this were to happen, the savages already converted would lose heart, those partly converted and those requesting the gift of Holy Baptism, would go lukewarm, those who disbelieve would laugh at the Black Robe, at their friends who have already become Christians, and at the religion that was preached to them. The spiritual fruit gathered so painfully last year would be lost, with disastrous consequences which could not be put redressed for many years to come.

and

It’s hard to imagine how much harm and damage the Canadian Priest Modest Demers has done to all the Evangelising Missions and to Religion itself throughout this region; he is known as ‘the liar,’ and it’s for this reason that many savages have taken back their two, three, and even six wives, whom they had repudiated following the sermons.

In one of his final letters, Nobili included a letter from the Father Superior of all the missions with the news that he was to abandon his plans and leave the Okanagan where he was building a home base, “I would really like to have nothing but good news to announce to you: but, alas, it is not so: everything I have to tell you will only make your heart bleed. But I have no doubt that you will resign yourself to anything that the Lord has decreed through Our Reverend Father General … That Reverend Father limits the field he has allotted us to the high country on this side of the Colombia, leaving all the rest to the secular clergy and to the other men of the cloth, who are said to accompany Monsignor Apostolic Vicar. So, if this letter reaches you, you may derive from it the measures to be taken as a result: if you have not started a settlement, do not start it now; let instructing these people satisfy you … Next Spring do not leave anything behind, neither animals nor possessions, but instead bring everything back to Colvile or Walla-walla. I am sure I don’t need to remind You Reverend Father to perform punctually all your spiritual exercises etc. I am sure that by the same token you understand, my very dear Father 1, that your labours must be such that they could be easily understood and resumed by your successors.“

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I received the Nobili letters from my friend, Sage Birchwater, whose most recent book is Talking to the Story Keepers: Tales from the Chilcotin Plateau. Plus, I am grateful for the advice he provided at the last stage of writing this article. He initially received these letters from wildlife biologist and conservationist, Wayne McCrory, who has written a book about the wild horses of the Nemiah Valley, which hopefully will be out this fall or next year. Much appreciation goes to University of Victoria Professor Emeritus, Wendy Wickwire, who did an extensive edit of my draft. As well, I am most thankful for the help historical geographer and Secwepemc Museum archivist, Ken Favrholdt, provided me during the research phase. And I am always thankful for the proof-reading that my dear wife Kathleen provides for nearly all my writing. In addition to the letters and De Smet’s book, Missions and Travels in over the Rocky Mountains, 1845, 46, I was able to glean information about Nobili from an article by David Gregory in the 62nd Report of the Okanagan Historical Society and various publications found on websites.