[A version of this article appears in the Sept. 23, 2023 Globe and Mail ]

We attended our first environmental conference in 1989, at which David Suzuki was reduced to tears when he described what could happen if humanity did not address climate change by reducing carbon emissions as soon as possible. Although my focus in succeeding years was advocating for wilderness protection and improving forest management, the climate issue was always in the background.

In 2003, we witnessed flames in the hills behind Chase on a Friday night while returning home from a Roots and Blues festival, where ashes were falling from a nearby fire above Silver Creek, and we called it in. By the following evening, the Neskonlith fire had grown huge, and we were on evacuation alert. Firestorm 2003 was a wake-up call, and in succeeding years I worked hard to advocate for climate change mitigation. After realizing how emissions were only increasing, my focus shifted to adaptation, as then and even more so now, our biggest concern is survival.

Despite the increasing amount of forest area burned as temperatures increase and intense weather events becoming the norm, governments continued to delay efforts to fire smart communities, while they carried on subsidizing oil and gas industries. This year, when the UN chief changed the term to climate boiling, the writing was on the wall given the severe drought.

Knowing it was not a question of if, but when a fire could hit us, we began work a few years ago to fireproof our property, by removing small trees, trimming branches, and removing the junipers next to our home. Last fall, we chose to selectively log our property and made sure to remove most of the trees near our home and then this spring we replaced the wood siding on one outside wall of our log home with metal. Yet, there was not time to do much clean-up, thus much of the logging debris was left and we had plans to pile and burn it this fall.

After lightning started two fires on either side of Adams Lake on July 12, my initial concern was the same as in previous years, why were these fires not put out initially. The reason is obvious, as Canada has not made the investment in the resources needed to adequately fight wildfires. Federal politicians focus more on purchasing fighter jets and warships, than buying the water bombers and water skimmers needed to douse fires when they first start, while provinces have far too many other priorities.

Then my dread about what could soon come intensified on July 20th when the Adams Lake East fire exploded and became visible that evening in Squilax. Yet, adequate resources were not put on the fire until it nearly burnt homes on the lakeshore, but by then it was too late. Once fires reach a certain size, only a change in weather will put them out. A few weeks before the big firestorm, the BC Wildfire Service (BCWS) set up a large camp at the Squilax airstrip, as if they knew what was coming.

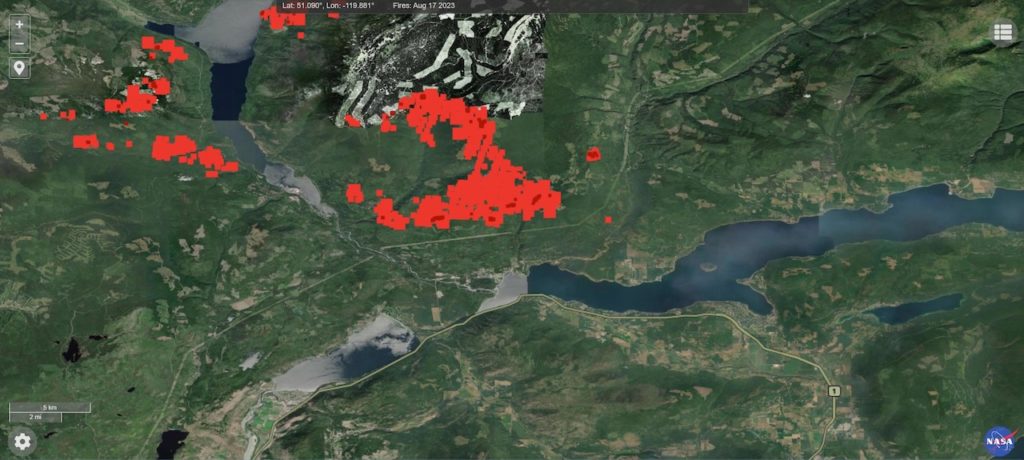

There is a NASA website that is updated daily with a satellite map that shows fire hot spots across North America, and I watched it like a hawk. Seeing the fire move closer to us, our concerns grew stronger and on August 17th when the BCWS announced their plans to do a controlled burn in the hills above us, our fears intensified even more.

During the afternoon before the controlled burn, a BCWS crew arrived and installed a 25,000-gallon water tank on our road and ran hoses to sprinklers on the roofs of most of the homes near us. I had already been sprinkling the hillside behind our home and these sprinklers would be able to add to my efforts. Shortly after 5pm, we witnessed and took photos of a giant mushroom cloud of smoke rising in the hills and from the lake I took a photo that showed the smoke drifting eastward. That night, the sky was red.

The following morning the sprinklers were on and BCWS announced that their controlled burn was a success, so we breathed a sigh of relief. Then at noon, our daughter was driving through Scotch Creek, saw flames in the hills and phoned immediately to urge us to evacuate. Fortunately, we had our essentials packed and ready, and thus we soon left. It took the CSRD another hour and a half to issue the order for Lee Creek and Scotch Creek and by then it was too late for those who ended up evacuating by boat or driving to Seymour Arm. They did not issue the order for Celista until after most of the homes had burnt. It was a miracle that no one died.

The 2023 Shuswap firestorm became a multi-headed colossal monster, as the fire on the west side moved south to Sorrento and Turtle Valley, while the fire on the east side went past Celista. Over 300 homes, buildings and businesses were reduced to ashes, and much of the forest is burnt to a crisp. Our home place that we love and cherish has been forever changed, the magnificent trails we love to hike are black and grey, the wildlife habitat is gone and now we fear the inevitable landslides and floods that will come when heavy rain falls where the moisture cannot be absorbed because the trees are dead, and the soil is burnt.

Residents were the heroes after the firestorm

On August 19th, the day after the firestorm, I returned to find that our home survived, and the fire had only reached the green hillside that had been watered. There was no time to clean out the freezers and fridge because we had to work on a spot fire that threatened our well shed and if it grew larger, our neighbour’s home. A BCWS team arrived, but refused to help because they were tasked to only attend to fires immediately threatening structures. Thus, we had to use buckets of water from our pond to douse it.

Putting out spot fires is akin to playing “whac-a-mole,” as no sooner are the flames put out than they rise again, because these fires are underground in roots and stumps. Fortunately, there were fire department trucks and crews from all over the province and two showed up that day to work on our spot fire, along with one of our many local heroes that remained behind to protect homes and properties. That spot fire persisted for nearly a week, and although I had to leave, my neighbours monitored it and contacted both locals and more fire trucks who continued to wet it down.

We will be forever grateful for the heroic efforts our neighbours did to protect properties and homes by working day and night putting out spot fires, including one that was enormous. Throughout the North Shuswap, hundreds of residents remained behind or returned to fight fires including our CSRD Area F director, Jay Simpson. These heroes are not average citizens, as many are contractors, loggers and ranchers with years of experience working in the woods, including many who have fought fires for years. They utilized many dozens of home-made fire trucks with tanks, pumps and hoses, as well as heavy equipment to build fire guards and some worked collaboratively with BCWS personnel.

Despite their essential service to our community, these local fire fighters were under strict orders to remain on their properties and dozens of police and conservation officers, including some from Vancouver, were brought in to enforce the evacuation order. Roadblocks were set up along our highway at bridges and spike belts were used to prevent vehicles from evading the checkpoints. Thankfully, many local boat owners from communities across the lake helped transport people and bring in supplies, until police and conservation officers began monitoring the lake with their watercraft and threatened to seize boats and issue fines.

Yet, despite the strict rules and heavy enforcement, our resilient and resourceful community firefighters found ways to evade the authorities and obtain food and supplies, including fuel for their equipment and water for their hoses. Thus, countless homes and properties were saved from the fires, but they could not protect every house and a few more structures were lost to spot fires a few days after the firestorm.

The BCWS was very challenged by this firestorm, as they had to evacuate their camp in the afternoon of August 18th, when the fire raged through Squilax, burning many of the firefighter’s tents before destroying 85 homes, cabins, and businesses on the reserve. The fire then jumped the Little River and raced up Squilax Mountain and into Turtle Valley, while some band members including Skwlāx te Secwépemc Kúkpi7 James Tomma huddled under the bridge.

It took BCWS a few days before personnel and equipment could return to effectively work on the fire. In some areas of the community, including Celista, there were no government fire fighters for stillfive days and thus only locals were there to protect homes. Finally, after two weeks, BCWS recognized there was a need to utilize locals to help with firefighting efforts. After locals helped organize a 10-hour training course, approximately 30 residents were paid to work 12-hour shifts side by side with BCWS staff to put out spot fires, yet they were still denied food, supplies and fuel.

It was unconscionable for government authorities to enforce these strict evacuation order regulations, while not recognizing that if it wasn’t for these rural residents many more homes would have been destroyed. One might hope a review of the Shuswap 2023 firestorm will result in much needed changes, so that in the future residents will be able to legally protect their homes and properties as is the case in other jurisdictions around the world.

The BC government has yet to implement previous wildfire review recommendations, but the disastrous Shuswap firestorm should finally provoke the BCWS to be both more proactive in putting out fires when they are small using all the best technology available, and to put a far greater effort at reducing fuel loads surrounding rural communities. Given that statistics clearly show how the annual area in British Columbia burned by wildfires has increased 20 times compared to the pre-year 2000 average and this year the total is already over 2.4-million hectares, it is long past time for urgent action.

POSTSCRIPT

Scenes of destruction

Lee Creek

Scotch Creek

Celista