What the canal might have looked like if it had been built

What the canal might have looked like if it had been built

Often, some of the most interesting history stories are the footnotes, the obscure tales about the disreputable characters, the disputes, the failed schemes and the development pipedreams. One of these vignettes was the very early proposal to build a canal to provide a transportation link between the Okanagan and the Thompson region through the Shuswap.

After the explorers, the fur traders and the gold seekers came the surveyors, who were scouting out the region for arable lands, timber, potential mines and transportation corridors. In 1874, a railway engineer named Marcus Smith was surveying the Okanagan Valley and noted in his report that the north end of the valley was only 18 miles long and that it was possible to make the journey north to the Spallumcheen River (now called the Shuswap River) using a canoe through the existing series of swamps and ponds. He noted that a canal could be built at a low cost to connect the two waterways.

As settlers began to move to the Okanagan, the major transportation link from the coast was the sternwheelers that moved freight to Fortune’s Landing, where it had to be loaded onto wagons and hauled to the head of Okanagan Lake. From there, goods were loaded onto boats for the final haul to Okanagan Landing. The proposed canal was seen as the solution to improve the movement of goods and people and as the route went through fine agricultural land it would quickly become settled and productive.

Moses Lumby, photo courtesy of the Vernon Museum and Archives

Moses Lumby, photo courtesy of the Vernon Museum and Archives

In April 1882, the Inland Sentinel newspaper published an article about the proposed canal suggesting that the federal government look after the canal’s construction. The major advocates for the canal were Preston Bennett, a Spallumcheen farmer and the local member of the provincial government, his partner Moses Lumby and Thomas Wolfe, rancher and business associate of Cornelius O’Keefe. Later in 1882, the Dominion Government Minister of Railways and Canals, Sir Charles Tupper, instructed L.B. Hamlin to leave his work overseeing the construction of the CPR to survey the proposed canal route.

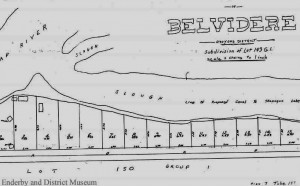

Map showing proposed location for canal – Belvidere was an early name for Enderby – image courtesy of Enderby Museum

Map showing proposed location for canal – Belvidere was an early name for Enderby – image courtesy of Enderby Museum

Hamlin’s report was less than optimistic about the proposal, as he determined that four or five locks would be needed along with considerable excavation work with the estimated cost being $27,000 per mile. When Joseph Trutch, the then Dominion Government Agent in Victoria forwarded the report to Tupper he commented that the estimate was too low. The following year, the provincial government sent another report to Ottawa urging that work on the canal begin immediately, but the House of Commons did nothing as they felt the costs were too high for this early stage of development in the west.

As construction of the CPR progressed, a plan to build a spur line to the Okanagan from Sicamous was hatched and not long after the last spike was driven in, the Shuswap and Okanagan Railway Company was incorporated. Survey work commenced in 1890 and within a year the tracks were laid and the first passenger train reached Vernon in October.

Captain Thomas D. Shorts, photo courtesy of Vernon Museum and Archive

Captain Thomas D. Shorts, photo courtesy of Vernon Museum and Archive

Despite the plans for the railway, there remained one strong advocate for the canal. Captain Thomas D. Shorts moved freight on various steamboats in Okanagan Lake. When he unsuccessfully attempted to get government support for the canal, he tried to interest private financiers and made an application for a charter to dig the canal as a ditch between Fortune Creek and Deep Creek.

We are fortunate to this day that the canal was never built, as not only would it have been difficult to operate especially during the winter due to the ice, but it would have caused major ecological damage to the watershed. With so much water exiting the system, our lakes would have become dangerously low in the fall and winter, with the Little River and the Sicamous Channel nearly dry.

The canal was not the only proposal to divert water from the Shuswap to the Okanagan. In 1967, the then Premier W.A.C. Bennett announced a plan to use a $6-million agricultural fund to construct a dam and a diversion channel to use Shuswap water to clean up Okanagan Lake. Opposition to the plan grew quickly, led by the Shuswap-Thompson River Research and Development Association (STRRADA) with its thousands of members. By 1972, the proposal was dead, as the opposition grew to include local governments and chambers of commerce.

POSTSCRIPT

Another leading advocate for the canal was Robert Wood, who influenced the Dominion Government to explore the proposal. He proposed that the boats move through the canal by being towed with a chain, as he was concerned that the wake from the paddlewheelers would erode the banks of the canal.

Some eighty years later, the proposal to divert water flow from the Shuswap to the Okanagan prompted a detailed government study by DFO, the Pacific Salmon Foundation and the B.C. Fish and Wildlife Branch in 1969. Various means of providing the water flow needed for irrigation in the Okanagan were discussed, including a dam to raise the height of the water to allow for the water to flow south by gravity feed and the use of massive pumps. Another dam was proposed to hold water in Mabel Lake and Sugar Lake for storage to minimize low water in the Shuswap and Thompson during the late fall. The fisheries experts recommended that screens be used to prevent Thompson River salmon from heading south to the Okanagan.

The report stressed that without the provision of protective measures, the water diversion would eliminate the runs of salmon and Kokanee in the Shuswap River and rainbow trout in tributaries of Mabel Lake. The experts theorized that the best option would be to pump the diverted water from Mara Lake. Thankfully, the crazy scheme was axed, but it is always possible that water needs in the Okanagan could one day revive the proposal.