I was inspired to write this history of my father’s family by cousin Phil Greenberg, who sent me digital copies of old family photos. In 1987, Phil retained an oral historian to interview our grandmother’s cousin Rose Pilpel, who as a young child spent many of her primary school holidays with her grandparents (and our great-great grandparents), Liba Rischl and Moshe Frank (or Moishe, which is the Yiddish spelling) in Sejny, Poland.

As well, Phil interviewed our Grandmother Ann and had the recording transcribed. His mother, my Aunt Ruth, also valued our family history and wrote a booklet, The Max and Jennie Story, based on the time she spent with her grandparents.  Additionally, our distant cousin Elana Elav (the granddaughter of Moshe and Liba’s son, Eli Solomon) who lived in Israel prepared the lengthy family tree, which was updated by cousin Sue Frishberg.

Additionally, our distant cousin Elana Elav (the granddaughter of Moshe and Liba’s son, Eli Solomon) who lived in Israel prepared the lengthy family tree, which was updated by cousin Sue Frishberg.

Elana Elav

Other background information includes my father’s essay about his father, Ben Cooperman; census and other documents; and copies of letters written by my great-grandfather Max Cohen. Much appreciation goes out to cousin Phil Greenberg for his help and detailed edits of this essay that included additional key material.

We can make available to interested family members any of the source documents and/or recordings referred to above. We particularly recommend the Rose Pilpel transcript and The Max and Jennie Story. These first-hand accounts of our forebears are true family treasures.

This history will be in three parts, Part 1 -Sejny, Part 2 -St. Paul, Part 3 – Grand Forks, North Dakota

Introduction

Ancestry research is a popular obsession for some people, but it is not a pastime that I have been interested in until most recently when I finally paid attention to some old family photos, many that I have seen before, and to recorded stories sent to me by my cousin, Phil. These photos and stories rekindle the pleasant memories of the times I spent many years ago with my parents and relatives at homes and synagogue. There was a spirit of kinship between grandparents, uncles and aunts and cousins that bonded us together that is missing today in our digital world, where fewer and fewer families have cultural ties. My own lack of connection to my family is due in part to having left the U.S. in 1969, which isolated me from my relatives. Now with some spare time, I have taken on the task to research and write this history, with a goal to share this essay with all my distant cousins that can be located.

One of the most fascinating aspects of learning about my ancestors is gaining the ability to connect my life with their lives. I can now compare how I lived my 70 plus years, with how they lived theirs. It is intriguing to recognize the similarities between my great great grandparents, my great grandparents, my grandparents, my father and myself that have also been passed on to my children.

Our Jewish ancestry stretches as far back into antiquity as the Torah takes it, some 6,000 years. Over this time-span, Jews were routinely slaughtered or endured harsh persecution. Although in some places and times some achieved great success and substantial wealth, for many centuries life for most Jews was most difficult and challenging.

Poland, where most of my family is from, is a distinctive example, as Jewish emigration from Western Europe began in 1098. In the 12th century, Poland’s ruler Boleslaw III encouraged the migration to foster commercial development and they were employed in his mint as engravers and supervisors. Two hundred years later, the Catholic Church pushed for persecution, but many Princes did not support this due to the profits the Jews generated. Jews once again flocked to Poland during the reign of King Cashmir III, who apparently had a Jewish lover. When Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many more emigrated to Poland, which became the European center of the Jewish world, although their situation fluctuated a number of times more until Russia took control in 1795 and persecution began again in earnest.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, Jewish communities had grown substantially in Poland. In the many scattered shtetls and rural communities, Jewish life was often marked by poverty and racist persecution. In the cities, there was a different mix: many who lived in grinding poverty, yet also others who enjoyed commercial and professional success and who founded successful Jewish social institutions and a thriving artistic and intellectual community. But in the late 1930s and early 1940s, all of the latter was shattered and obliterated by the Holocaust. Moreover, many scholars in recent years have documented the widespread role of Polish citizens throughout the country who turned on their Jewish neighbors, murdering them and seizing their property.

The same cultural traditions and family traits that helped our ancestors survive under what were often-difficult times in Poland continue to serve our relatives. These survivors in the old country who emigrated to America had children who were successful, and this pattern continues to repeat itself.

Part One – Sejny, Poland (annexed by Russia from 1795 to 1918)

The story begins in 1860, when my great great grandparents, Liba Rischl and Moshe Frank’s first child, my great-grandmother Jennie, was born. They lived in the small town of Sejny, Suwalki Province, Russia. Today, the town is in Poland near the border with Lithuania and has a population of approximately 6,000 people. Moshe had a business that provided vestments for the Catholic clergy. Sejny had a well-established Jewish community and was then somewhat of a refuge from the intense persecution under the Russian Czars.

The White Synagogue in Sejny, Poland

During the same year that Jennie was born, construction began on a new, stone synagogue to replace the wooden temple built in 1768 with the help of the Dominican Order who wanted to encourage commercial activity by attracting Jewish people to settle in the town. Although it was nearly destroyed by the Nazis, the restored building now known as the White Synagogue serves today as a museum for the Borderland Foundation, which focuses on the recovery and celebration of the rich East-Central European regional heritage.

The Russian government’s endorsement of Jewish persecution was formalized in 1804 when Alexander I created the “Statue Concerning the Organization of the Jews” that required Jews to assimilate by forcing them out of their rural villages into ghettos. Jews were forced to live in poverty in the area known as “The Pale of Settlement,” which included Sejny. Only a limited number of Jews with university education, or those who were affluent members of merchant guilds or were military personnel were allowed to live outside The Pale.

It was Catherine the Great who had first created The Pale in 1791, after many failed attempts by her predecessors to remove Jews from Russia entirely unless they converted to Russian Orthodoxy. The expansion of the Russian empire through the annexation of Polish-Lithuanian territory substantially increased the Russia’s Jewish population, which at its height totaled over 5-million people and represented approximately 40 percent of the world’s Jewish population.

These rules became more relaxed beginning in 1855 under the reign of Alexander II, but when he was assassinated in 1881 the crime was falsely blamed on a Jewish conspiracy and the government launched a wave of state-sponsored massacres known as pogroms. Hundreds of Jewish villages were burned and Russian soldiers and peasants slaughtered thousands of Jews, although most of the violence was centered in Russia rather than in the annexed territory of Poland.

Times improved during the rule of reform-minded Alexander II, who freed the serfs and revoked many of his father’s harsh edicts against the Jews. Life for the Frank family in Sejny must have been secure and prosperous as Jennie had six brothers and sisters; Malka (b. 1864), Eli Solomon (1865), Leah, (b.1867), Chaie (b. 1870), Louis David (b. 1873) and Miriam (b.1878). Moshe, like most of his contemporaries, was a deeply religious man who studied and prayed every morning and evening at the synagogue. His work often took him away to other communities where he took measurements and then returned with the finished vestments. He employed tailors to do the sewing, as his role was to run the business and cut the fabric. His eldest daughter, Jennie, began working at a young age in a small store.

In approximately 1875, a young man named Max Brznitski moved to Sejny from near Vilna, the historic capital of Lithuania which was then under Russian rule, to work as a clerk for the government. Max, who was born in 1859, was a half-Jew who was not religious. We know a little about Max and Jennie’s early lives from the stories they told at their 59th wedding anniversary party, which was recorded and later transcribed. Here is how Max described the first time he met Jennie:

I was a clerk in the courthouse and secretary to the mayor of the city. The law in Russia at the time was when someone received money from abroad; they had to come in for me to put a signature to prove they were a real citizen. This girl came around in my office as asked me to sign so the post office would deliver a $25 check her father had received. Well, I said, yes, I will, but you can keep the 5 kopeks (about 5 cents) for yourself, I’ll do it for nothing. When I finished my work daily, I had to pass her little store on the way home, where they sold sugar and jam, coffee and stuff. I used to go in there and buy a pack of cigarettes that sold for 3 kopek. If I handed 5 kopeks and she want to give me change, I’d say, never mind, keep the change. (All quotes have been edited)

Max and Jennie’s courtship lasted five years, despite Jennie’s father Moshe’s objections. As Max explained it, He wanted a rabbi and I was a half Jew. I didn’t go to temple often and I didn’t pray like all the Jews in that little town. But in the meantime, I was near her all the time. She didn’t mind what her father said and she fought like a tiger and was bound to have me or else nothing at all.

Here is how Jennie explained how her father finally relented:

When Max found out that my father was against him he wrote a letter that my father found and said “Aha, that’s why you’re so sad all the time. Well I’ll bring you another boy, that he’s educated in all kinds of languages and he’ll be better for than this one.” And I told my father, you can’t do this I like him and I want him. Four years went by and nobody knew that I went around every day with him. But I had two sisters, one a snitch and the one protected me. Finally, my father saw that nothing could be done, so he told my mother, “well, Liba Rischl, you tell Shenken (my name) that she can tell this boy he should come in. I’ll talk with him.”

Max and Jennie were married on December 15, 1880. Jennie recalled, There was a little snow on the ground. When I went to the altar the boys in the back of me stepped on my dress and veil, so I kicked them.

On March 13, 1881, Alexander II was assassinated and it did not take long for the persecution against the Jews to start again and Sejny was not immune to the problems. Max lost his job in government and his pal Avram emigrated to the U.S. from where he sent letters back to Max. According to Max’s account at the anniversary party, Avram wrote, “You’re a foolish boy, why do you want to stay in a dictator’s country? They take away your rights and they take away everything else. Come over to this country. It’s a free country, free speech, free press, everything free and if you’re good enough, you can obtain a job here.” So even though Jennie was pregnant, in mid-1882 Max left for the U.S. and promised to write her about how he was doing and send for her when he had made a successful start.

Jennie gave birth to my grandmother Ann in October 1882. After receiving news from Max that he had a job and place to live, she emigrated the following year to join her husband Max in St. Paul, Minnesota. [There is a much different version of how Jennie came to find Max in The Max and Jennie Story, than the one Jennie and Max told at their 59th anniversary party. Ruth wrote that after Max had emigrated to the U.S., Jennie and baby Ann lived with her parents. Max wrote seldom and they didn’t know where in the U.S. he was. Jenny decided to take their child to the U.S. to find Max. She arrived in New York with her baby Ann and a photo of Max and she was forced to search for him. After running out of money while in Chicago, where worked for a tailor making button holes until a passing drummer recognized the Max in the photo and directed her to find him in St. Paul.] Grandmother Ann recalled during her interview that she came to America with her mother and they headed directly to St. Paul, where Jenny and Max were reunited.

Given the hardships and lack of opportunities they faced under the harsh regime of Alexander III, Jennie’s other brothers Eli Solomon and Louis David and her sister Leah also immigrated to the U.S. Her sister, Malke remained in Poland and perished in the Holocaust. Sister Chaie immigrated to Israel and her youngest sister, Miriam (Mary), immigrated to Australia in 1938 to join her daughter Rose, who was born in Sejny in 1904.

Jennie’s sister, Miriam (Mary)

In 1987, Rose was interviewed and the recording was transcribed. From this transcript, we learn much more about Moshe and Liba and what life was like in Sejny in the early 1900s. Rose lived in Bialystok, a city near Warsaw that supplied textiles for much of Poland. Her parents, Mary and Ephraim Prowalski owned one of the textile factories. She recalled how when the Bolsheviks came in 1919, they confiscated everything and left her parents worthless coupons. Her father then became a wholesale supplier of goods to shops. He saved his money and used it to construct a building with 10 flats and two shops where they lived on the top floor.

Rose (top) with her twin brother and sister, Joseph and Zina and her parents Miriam (Mary) and Ephraim Prowalski

When Rose was a youngster in primary school, she often visited and stayed during summers and holidays with her grandparents, Liba and Moshe, who would have been in their early 70s. At this point in their lives, they lived quite simply in a small, 3-room house adjacent to their daughter and husband who ran a simple printing business and sold school books, stationery, wallpaper and pens and pencils. Rose does not provide her aunt’s name, but likely she was Malke (and her husband’s last name was Bobrovnik), given that she does not mention that her aunt had children and no children of Malke are listed in the family tree. Her aunt was considered an intellectual and she helped by doing all the proofreading. Rose slept on a couch in her Aunt’s house during her visits.

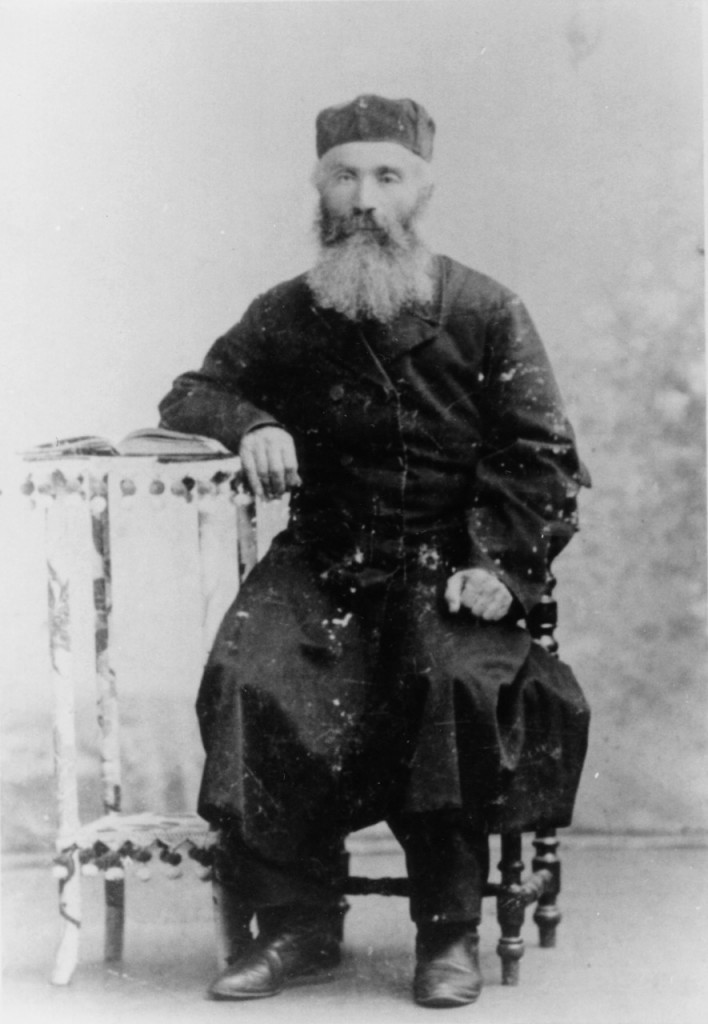

Rose described her grandfather Moshe’s occupation as being very unusual for a Jew, as he supplied the expensive vestments for hundreds of priests and bishops in the region. This was an art and he was the cutter and employed two or three men to do the sewing. He had a man with a horse and sulky who transported him to do the fittings and deliver the finished vestments. In the winter the vestments were made of warm kaftan and lined with sable. At times, Moshe would stay overnight with the priests, many of whom were friends. He made a very good living, but lived quite simply. Her grandmother Liba looked after the house and did all the cooking and cleaning. The laundry washing was done in a trough, which was extremely time-consuming and primitive.

Rose described her grandfather Moshe’s occupation as being very unusual for a Jew, as he supplied the expensive vestments for hundreds of priests and bishops in the region. This was an art and he was the cutter and employed two or three men to do the sewing. He had a man with a horse and sulky who transported him to do the fittings and deliver the finished vestments. In the winter the vestments were made of warm kaftan and lined with sable. At times, Moshe would stay overnight with the priests, many of whom were friends. He made a very good living, but lived quite simply. Her grandmother Liba looked after the house and did all the cooking and cleaning. The laundry washing was done in a trough, which was extremely time-consuming and primitive.

Their home only had a small kitchen, living room and bedroom. There was no running water. Outside was a barrel, which was filled using buckets with water from the river that flowed by in their backyard. There were just a few kitchen implements and Liba cooked over a fire using a tripod. Often Liba would take meat, beans, and vegetables to the nearby baker who would cook it in his oven after the bread came out. During the WWI German occupation, they barely survived on rations and able-bodied men and woman were forced to work for the army digging trenches.

Here is how Rose described her grandmother, who spoke mostly Yiddish, “She was a very, very simple, humble, domesticated person. She didn’t envy anybody…didn’t try to keep up with the Joneses, like they do here, no, not at all. They were much happier. There was no jealousy of any kind. The neighbors were very nice, they used to go sometimes and visit one another in the evening. Sometimes they used to go to the baker. In the winter it was very cold, so the neighbors used to go and sit, and while the baker was baking the bread, to just sit there and talk and have a cup of tea in the evening. They were very, very simple pleasures.”

Rose remembers Moshe as a good-looking, kindly man who was very respected in the community. He was a very observant, Orthodox Jew, who went to the Synagogue twice a day, morning and night to study and pray and wore a long, white kaftan and silk tallis (or tallit, a prayer shawl with tassels). Often, he was looked up to for advice by his community and even by the non-Jewish people. He likely earned a good living, but he was very frugal and likely saved most of his money. Both Moshe and Liba had many friends in the community.

Early on in the interview, Rose told this story which reveals more about the stressful times and her grandfather’s personality:

Things were very, very primitive. They didn’t demand as much amusement or outings or anything like that now. They were very, very Orthodox. They kept strictly to their religion. Not that they didn’t have non-Jews as neighbors, but he was the head of the family and what my grandfather said just went, because he was head there. His sons, particularly one of them [likely Louis] was a very up to date fellow he was very progressive, who did not like to defy his father but he did not want the future his father was looking for and he was [dismayed about the lack of opportunities].

So he was unhappy for quite a while. He used to go to the Synagogue very religiously when the occasion arose. And one day, when his father was away, he went to the safe, where his father kept his money. He didn’t want to pinch the money but he had no option. He took an amount of money and left a note to say that he was very sorry to cause the disturbance and upset his father, but he hoped to repay it some day. Well, when my grandfather came home, and he discovered the missing money. He immediately engaged a fellow with a horse and sulky, and he knew where he was headed for. They drove very, very fast and because the son had not managed to get too far away, they met. My mother used to repeat it a dozen times how they embraced one another, then started crying, and my grandfather broke down and he said, ‘Well, I can’t keep you here against your will. But I don’t want the people in Sejny to know that you left because I wasn’t treating you well.’ So he said, because of what people might say, you’d better come back with me. When you cleared out, so to say, you didn’t have any clothes on other than what you were wearing and I want to fit you out with a few suits and trousers and what goes with it and give you a send off and then you can go where you want to go with my blessing.’ So he did. He came back and then went to the States later. [edited]

This may be a photo of Moshe and Liba , circa 1915 (unverified photo)

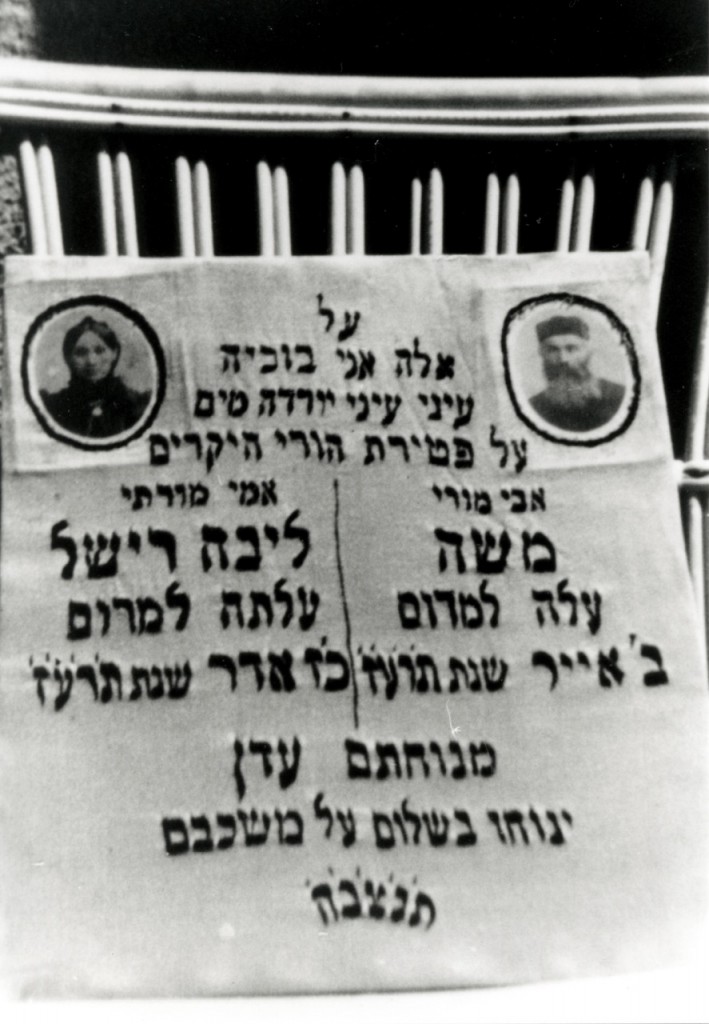

Moshe and Liba both died in 1917, just one month apart. Although the Spanish Flu epidemic was raging across Europe then, Rose believed their death was due to the lack of food available during the war. On their tombstone, is this inscription: “On these my eyes are weeping, My father, my teacher, Moshe, climbed to heaven, my mother, my teacher, Liba, also went up to the sky, will they rest in peace their souls will be remembered.”

Copy of inscription on Liba and Moshe’s gravestone

Rose fondly remembers his visits when she played with friends and swam in the river with nothing on. They also bathed in the river. They would go into the nearby forest and pick blueberries and blackberries. They celebrated all the Jewish holidays and observed the Shabbat, during which they were not allowed to work or write.

It is not clear when Rose immigrated to Australia, but the family tree notes that she married Joshua Pilpel (b. 1892 in Safed, Israel) in 1928 in Perth, Australia. In the interview, she explains how she could see WWII coming and sent her parents a permit to immigrate to Australia. They let the permit expire, because they did not want to come because they did not want to lose the wealth they had accumulated. She continued to insist they leave and they finally left at the end of 1938 just prior to the Nazis invasion of Poland. They had to pay someone 25 percent to smuggle their money out of the country.

As true with many families, the Franks have spread around the world. The only information available to date about our distant cousins is from the family tree prepared by Elana. Using this information, here are the names and the locations of Jennie’s siblings and their children:

Malka was born in 1864 and died in 1943 in Sejny in the Holocaust. She married a man with the last name, Bobrovnik.

Eli Solomon Frank was born in 1865 and died in New York in 1910. He married Fannie Hirsch in 1885. and they had nine children. Eli arrived in America in April, 1899 with daughter Ethel (Gordon) b. 1887. Fannie arrived in May with Lillie (Margolis) b. 1888, Louis (Leo) b. 1890, Mae (Fishman) b. 1892, Max b. 1894, and Abraham b. 1897. Hilda (Kovins) b. 1900, Harold b. 1901, and George b. 1904. wer born in New York.

Leah was born in 1867 and married Benjamin Wolfe. They had eight children, Sophie (Grossman), Ira b. 1889, Jack b. 1890, Joseph b 1891, Saul b. 1900, Dorothy b. 1902, Ben b. 1903 and Lorraine (Benson) b. 1908.

Chaie was born in 1870 and married Salman Sochowosky. They had two children, both born in Sejny, Zev Wolfe b. 1897 and Shlomo b. 1901.

Louis was born in 1873 and married Fannie Schwartz. They had three sons, Harry, Saul Edward b. 1900 and Irwin b. 1906.

Miriam (Mary) was born in 1878 and married Ephraim Prowalski and they had three children, Rose (Pilpel) b 1904 and twins Joseph and Zina (Junovitz) b 1909.