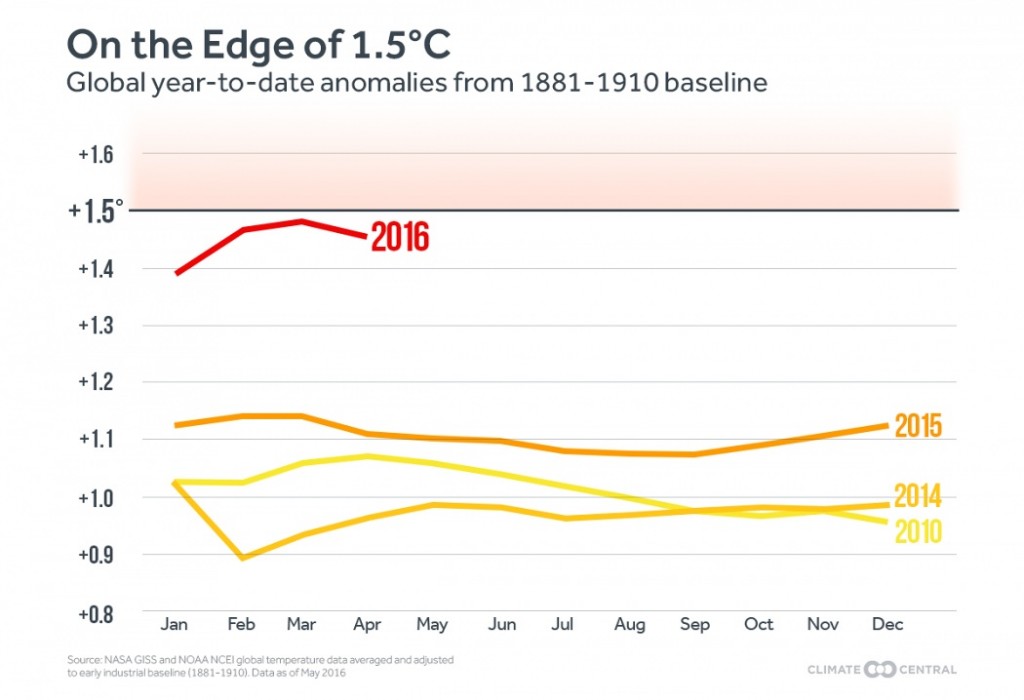

It appears as if the earth is entering a new phase of global warming, as temperature records are continuously being broken and impacts are increasing, including storms, floods, droughts and fires. In the Shuswap, spring arrived very early and many seasonal events are two to three weeks ahead, including the lake level, the emergence of natural vegetation and the ripening of fruits and vegetables. Another climate change impact not often considered is the melting of local glaciers.

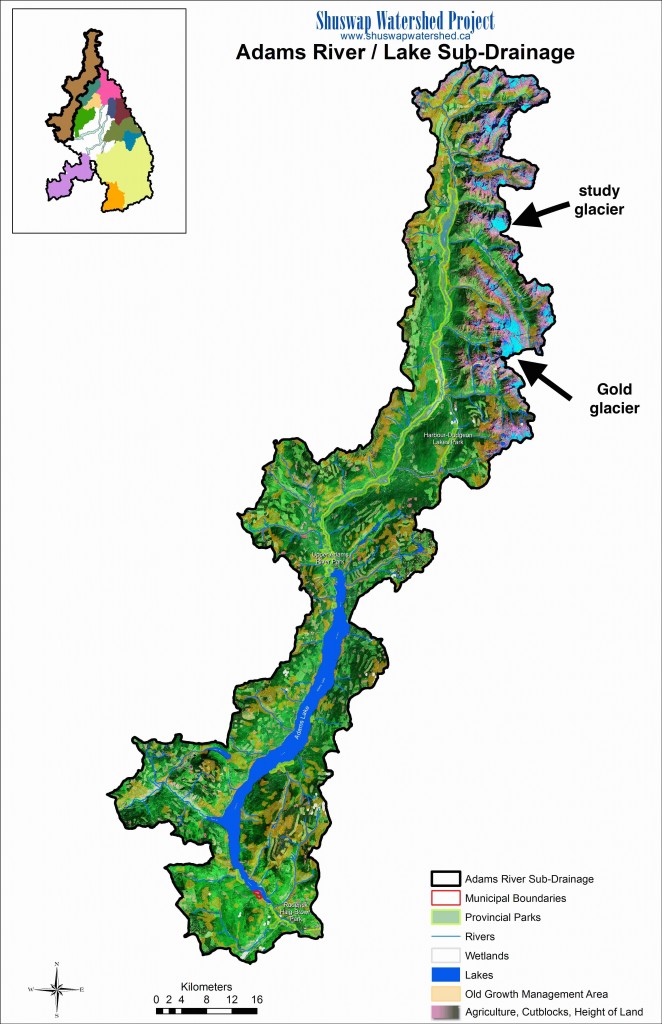

Most Shuswap glaciers are concentrated close to the north and east boundaries of the watershed, in the Adams, Seymour, Anstey, Perry and Eagle River sub-drainages. In the fall, much of the water coming down the Upper Adams River is from melting glaciers and you can see aquamarine coloured, glacial till water at the north end of Adams Lake and in Tum-Tum Lake.

The blue-green colour of Tum Tum Lake in the upper Adams drainage shows the water is from melting glaciers

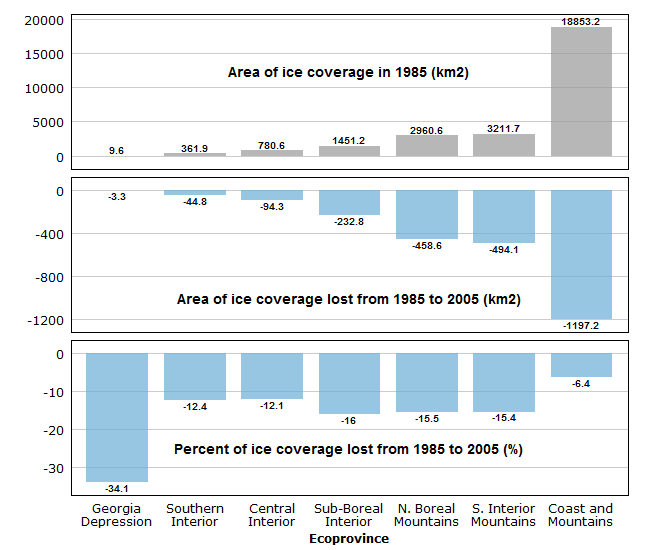

In 2005, the B.C. Ministry of Environment published a report that provided data on how much the glaciers retreated between 1985 and 2005. In the southern interior mountains the area of ice coverage declined by 12 percent and the volume decreased by 15 percent. Glacier melt was far more extensive in coastal mountains, especially on Vancouver Island where the surface area of glaciers declined by 34 percent.

An in-depth glacier study that included researchers at the University of Northern British Columbia was recently completed. It looked at the number, total area and the melting rate of a number of glaciers in B.C. and Alberta. At each site, research teams measured temperatures, precipitation, wind speed, as well as changes in thicknesses, volume, movement and sizes. In addition, they analyzed thousands of aerial photos, some of which date back 70 years and used LiDAR remote-sensing technology to create detailed models of surface topography.

The Wolverine Glacier in the Anstey River drainage has shrunk significantly leaving a lake where there was once ice, Google Earth Image

An article in the April, 2015 journal Nature Geoscience about this study explains how 90 percent of Interior and Rockies glaciers will be gone by the year 2100. The implications are quite serious and impacts could include very low river flows and lake levels after the spring run-off, reduced hydro generation, lack of adequate water levels for spawning salmon, and reduced water supply for agriculture and municipalities.

Glaciers visible from the Oliver Creek road above Tum Tum Lake are disappearing

Glacier melt in the late summer can provide upwards of 25 percent or more of the flow in many streams. When the glaciers melt, there could be far less water in the Adams and South Thompson Rivers, which could devastate the sockeye salmon and force the City of Kamloops to develop an alternative source of drinking water. If combined with earlier run-off, which we are seeing this year, the level of Shuswap Lake could be much lower in the summer.

Retired Okanagan College professor Tom Crowley has explored many local glaciers, hiking across them and even camping on them. Precautions are required to cope with the crevices, including each hiker being tied to the same rope 12 metres apart and carrying ice axes. Over subsequent years he has observed significant recession, especially on the Bourne Glacier where there was easy access in the 1980s and by the late 1990s, access was gone because a lake had formed where there was formerly ice.

The Shuswap Environmental Action Society has begun an initial study of local glaciers. Using satellite photos, a GIS technician is comparing the reduction in surface area of two glaciers in the Adams and Seymour River drainages between the 1980s and 2015. A fly-over is also proposed for early September to observe signs of recession including new lakes and moraine rocks left after glaciers recede.

The goal of this study is to spark interest to undertake more in-depth research in conjunction with Thompson Rivers University. Surface area is just one indicator, as depth measurements are also needed. To better understand the contribution of glacier water to local streams, researchers can determine the percentage of glacier-produced isotopes in water samples.

Given that climate change is now escalating rapidly, it is possible that the glaciers will disappear sooner that anticipated. Gaining more knowledge about Shuswap glaciers will help assist local communities with the efforts needed to better adapt to our rapidly changing world.

POSTSCRIPT

As glaciers melt, water levels in creeks and rivers in the fall can actually be higher than normal. Glaciers act like giant freezers in the alpine, slowing the melting of the winter snowfall. Once the glaciers have disappeared, the spring melting can occur much faster, resulting in much lower water levels in late summer and the fall.

Shuswap water issues have always focused on water quality, but as the glaciers disappear water quantity issues could become more of a concern. As climate change intensifies, problems from melting glaciers could occur sooner than anticipated.