Adjacent to the city of Enderby is the main reserve for the Splatsin Band, the most southern community of the Secwepemc Nation. Because of the distance from Kamloops, early ethnographers spent little time here and thus, there is lack of written information about the Splatsin, who officially changed their name from the Anglicized version, Spallumcheen, in 2014. Most of the information available now about their past comes from oral histories passed down over many generations.

Adjacent to the city of Enderby is the main reserve for the Splatsin Band, the most southern community of the Secwepemc Nation. Because of the distance from Kamloops, early ethnographers spent little time here and thus, there is lack of written information about the Splatsin, who officially changed their name from the Anglicized version, Spallumcheen, in 2014. Most of the information available now about their past comes from oral histories passed down over many generations.

The origin of their name comes from the late elder, Cindy Williams who explained that Splatsin, which is pronounced ‘splajeen,’ means riverbanks, which is where they lived along both the banks of the Eagle, Salmon and Shuswap Rivers. Their traditional territory was huge, extending from Mica Creek to the north to Kettle Falls, Washington to the south and from Monte Lake to the west and the Nelson to the east.

Their primary village sites were at Sekmas, from Old Town Bay to Sicamous and Splatsin (Enderby), where the majority of the population lives today. There were other major villages at Mara Lake, Mabel Lake and other locations that provided good fishing opportunities. When Europeans first began to arrive in the U.S., the Okanagan people were pushed north, eventually spilling into Secwepemc territory. Today, the large Okanagan Nation Reserve Number 1 extends into the Salmon River watershed and shares a border with Splatsin Reserve Number 2.

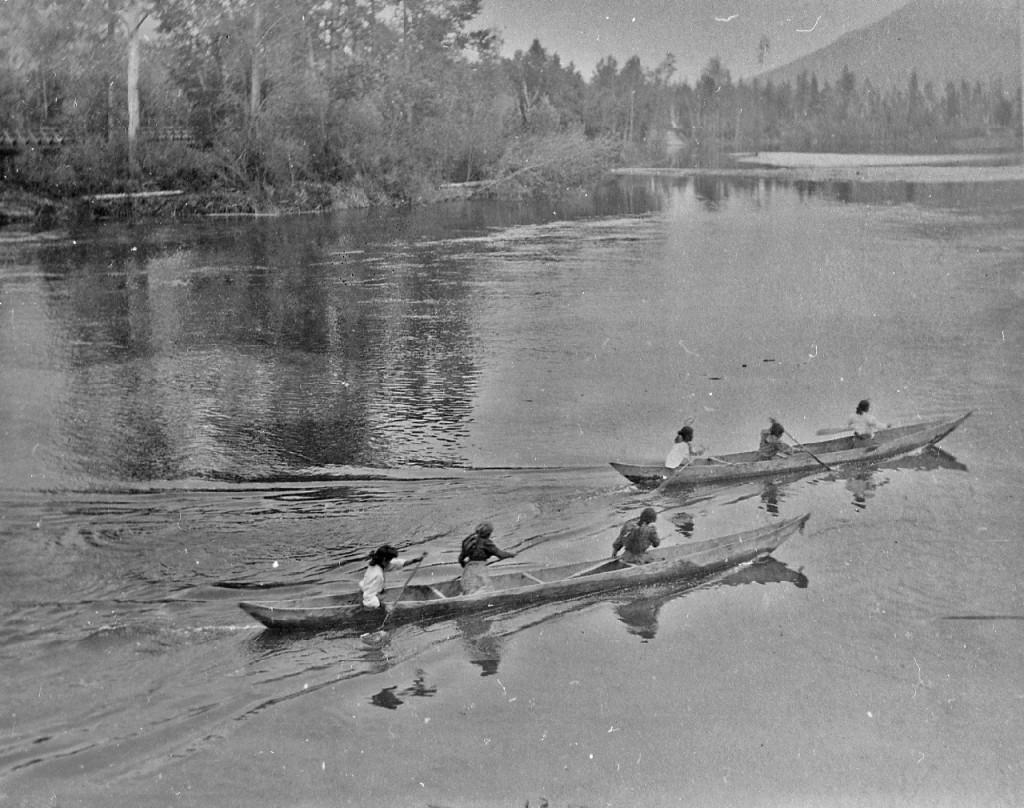

Splatsin women paddling cottonwood dugout canoes, 1908, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

Splatsin women paddling cottonwood dugout canoes, 1908, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

While the Splatsin share many similarities to other Secwepemc nation bands, there are also many differences. They speak an eastern dialect with many Secwepemc words pronounced differently. While the western tribes traded furs often, the Splatsin, because of their distance from the fort in Kamloops were less likely to have contact with the early fur traders. There are accounts that they did trade with trading posts at Eagle Pass Landing and near Vernon.

Splatsin fishing weir on the Shuswap River, 1891, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

Splatsin fishing weir on the Shuswap River, 1891, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

The Splatsin were warriors and fought many battles with other tribes to protect their borders. They also sought peace and in the end shared key fishing areas such as Shuswap Falls near Lumby, where they controlled the fishing to the north and the Okanagan people were able to fish above the falls, when salmon could still move upstream prior to the construction of the dam.

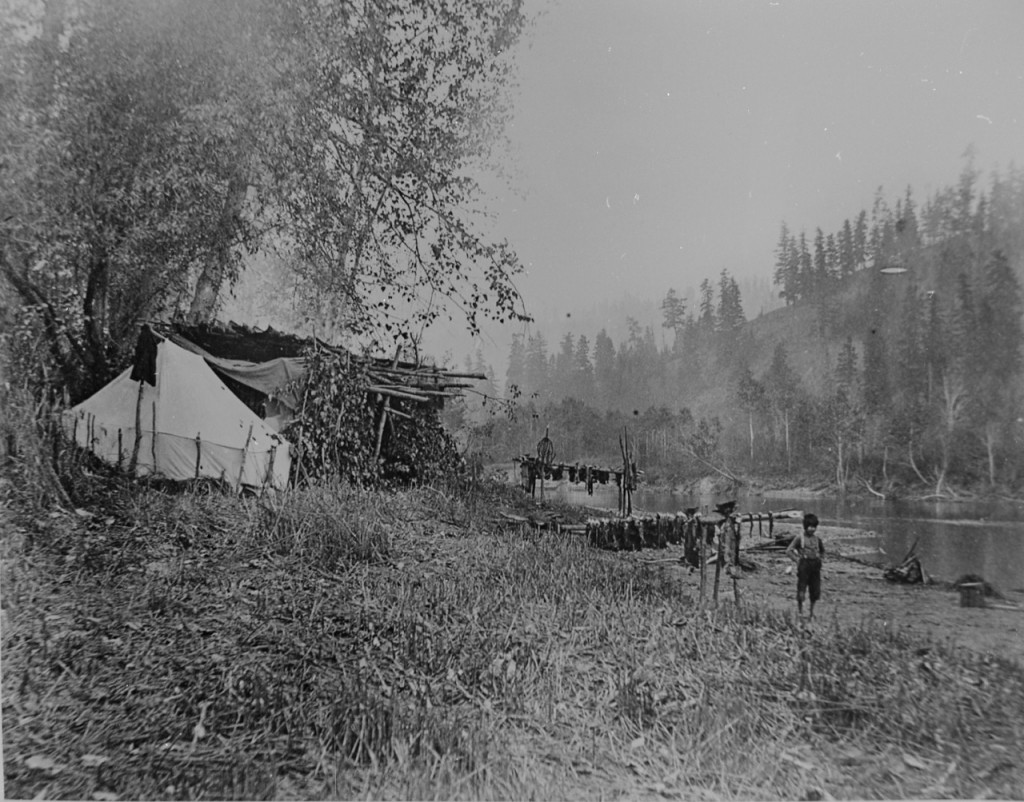

Fishing camp on the Shuswap River, 1891, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

Fishing camp on the Shuswap River, 1891, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

In addition to fishing, the Splatsin were great hunters and they had a tradition of seasonal rounds that included plant and berry gathering. Deer, elk and caribou were hunted in the hills throughout the territory and the meat was dried in their camps before the hunters returned to their villages.

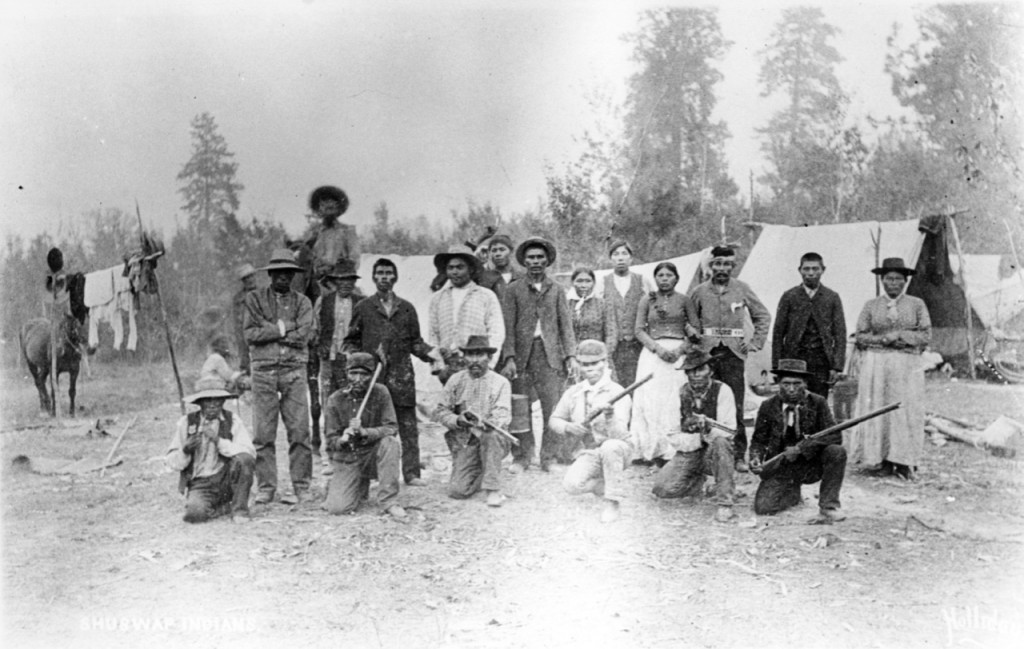

Waiting for the game warden, 1891, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

Waiting for the game warden, 1891, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

Along with their reputation as fierce fighters, the Splatsin were known to be reclusive and often hid when the Europeans entered their territory. However, the early settlers soon became dependent on the Splatsin for their labour. After the first sawmill was built in Enderby, the Splatsin became known as the premier log drivers on the river.

Splatsin men were the best log drivers on the Shuswap River, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

Splatsin men were the best log drivers on the Shuswap River, photo courtesy of the Enderby Museum

Initially in 1871, the Splatsin were only provided 200 acres of land for their reserve, which was most unfair given that white settlers could pre-empt 160 acres. Under the threat of war, the government enlarged many interior reserves in 1887 and the Splatsin allotment was increased to over 9,000 acres, including reserves at the Salmon River and Sicamous. However, despite strong opposition, the McKenna-McBride Commission reduced the size of the Sicamous reserve in 1913.

The new Splatsin Community Centre, built in the shape of a kekuli with a sod roof, is nearly finished

The new Splatsin Community Centre, built in the shape of a kekuli with a sod roof, is nearly finished

In recent years, the Splatsin have made some impressive improvements to their reserve, including the construction of a massive community centre built to resemble a kekuli pit house and a new, carved log-framed gas station and convenience store with meeting rooms. They are also promoting a cultural renaissance, with an emphasis on teaching their language and traditions to the new generation. Their development corporation, which includes sustainable forest management, environmental services and construction, is growing quickly.

The proposed ‘rail to trail’ would follow the western shoreline of Mara Lake, pictured above

The proposed ‘rail to trail’ would follow the western shoreline of Mara Lake, pictured above

As well, the Splatsin deserve much appreciation for working closely with the Shuswap Trail Alliance and local governments to convert the abandoned railway line along Mara Lake and the Shuswap River to a world-class hiking and biking trail.

POSTSCRIPT

There was not room to include two other key historical references to the Splatsin. In his 1891 “Notes on the Shuswap People,” George Dawson related a story told to him by the local Indian agent, J.W. Mackay In the story, Spokane chief Pila-ka-mu-lah-uh travelled north with news of the first encounter with Europeans. He was a “good raconteur, and from his vivid descriptions of the white men, their sayings and doings, became a centre of attraction, and was welcomed and feted wherever he went. He was next invited to the Kuaut, Halkam and Halaut camps on Great.Shuswap Lake, and, after spending a month at each of these places, he was further invited to Kamloops, where Tokane, the chief, gave him a grand reception.”

Chief Pila-ka-mu-lah-uh later met a tragic end when the chief of the Slat-limuh (Lillooet) Band did not believe his stories and killed him with his bow and arrow. A few years later, Spokane band members, now armed with rifles, attacked the Lillooets and killed many in retribution.

The other key historical note comes from the Neskonlith Claim to the Indian Lands Commission in 2008, which states,

“Traditionally, the Neskonlith, Adams Lake, and Little Shuswap Indian Bands, as one tribe, divided the lands they occupied among family groupings in a number of ‘settlement areas.’ The oral history of the community indicates that, during the period with which this inquiry is concerned, the members of that tribe recognized Chief Leon Neskonlith as their leader. Furthermore, oral history indicates that the Shuswap tribe was later divided into three separate bands (Neskonlith, Adams Lake, and Little Shuswap) by the Department of Indian Affairs.”

What this information indicates is the the Splatsin were a separate group within the Secwepemc Nation, likely due to their distance from the Neskonlith families.