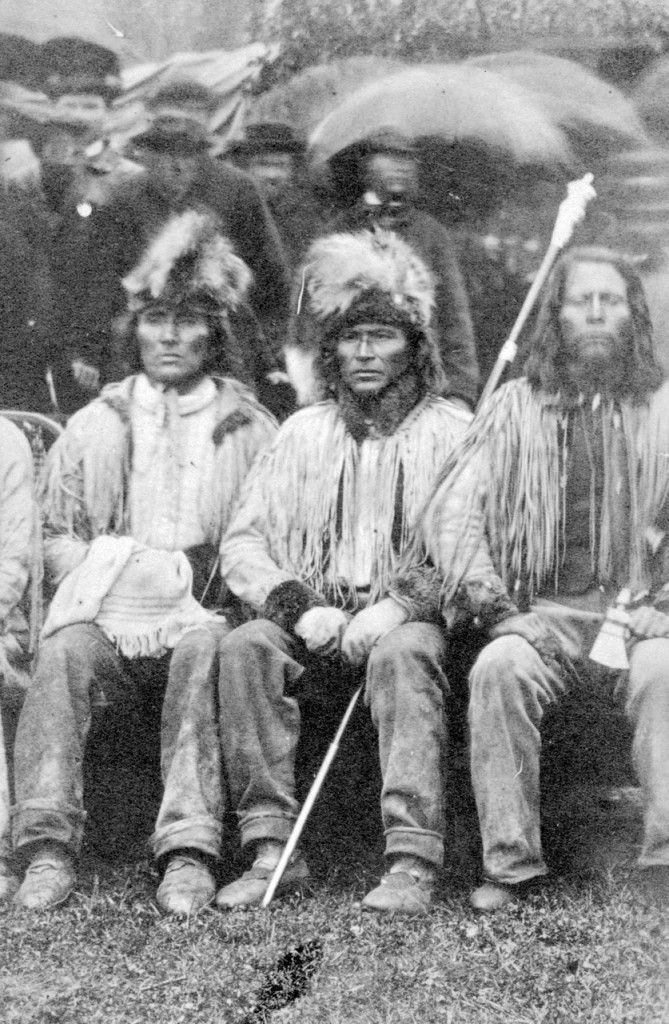

Shuswap Chiefs in Victoria, 1867 for Queen’s birthday, photo by Frederick Daily courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives

As communities prepare celebrations to commemorate Canada’s 150th year since Confederation, it is a good time to reflect on what the Shuswap was like in 1867. By then, the Secwepemc people had adapted to the impacts of the European invasion, but their numbers were fewer because of smallpox and other diseases brought by the miners. The fur trade, which had passed its peak in 1827, still continued, as the 1867 Hudson’s Bay Company journal has two entries about marten skins purchased from “Adam’s Lake Indians.”

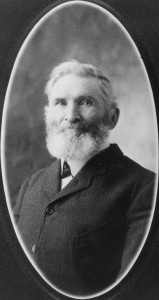

S.S. Marten in Kamloops, circa 1871. Photo courtesy of the Kamloops Museum and Archives

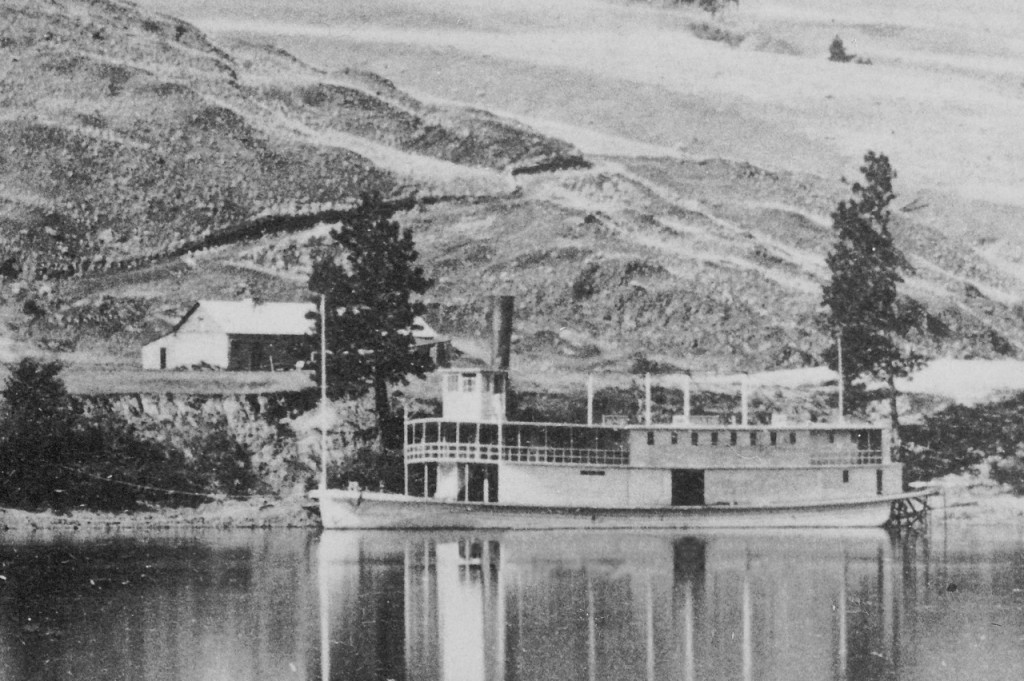

Most of the miners had arrived and then left the Shuswap after the big gold rush on the Columbia River in 1866 that resulted in the instant town of Ogdenville, where there was a trail to the Big Bend. The Shuswap’s first sternwheeler, the S.S. Marten, was built in early 1866 to service the incoming miners. However, by June 1867, the ship was tied up in Kamloops for repairs and there were doubts it would return to service because business was poor and stores had closed in the nearly deserted town, renamed Seymour City.

Gold miners in the Cariboo (no photos in the Shuswap) photo by Frederick Daily courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives

Some of the miners who arrived in 1866, chose to go to the mouth of the Eagle River instead of Seymour City, with hopes of finding a better route to the gold fields. Another boomtown, called Eagle Pass Landing, was established there with rough shacks, stores, and saloons, plus a depot, assay office, and blacksmith shop. While this town lasted longer than Seymour City, it too was abandoned within a few years and most of the buildings succumbed to fires.

The reserve system, which began in 1866 when the boundaries were surveyed, was the beginning of over a century of gross injustices heaped upon Indigenous peoples. It was the early settlers who had urged the government to create the reserves that allocated only 10 acres per family, whereas the settlers received up to 160 acres. In 1867, there were only a few settlers taking up land in the Shuswap, primarily where there were natural meadows for pasture and for tilling crops.

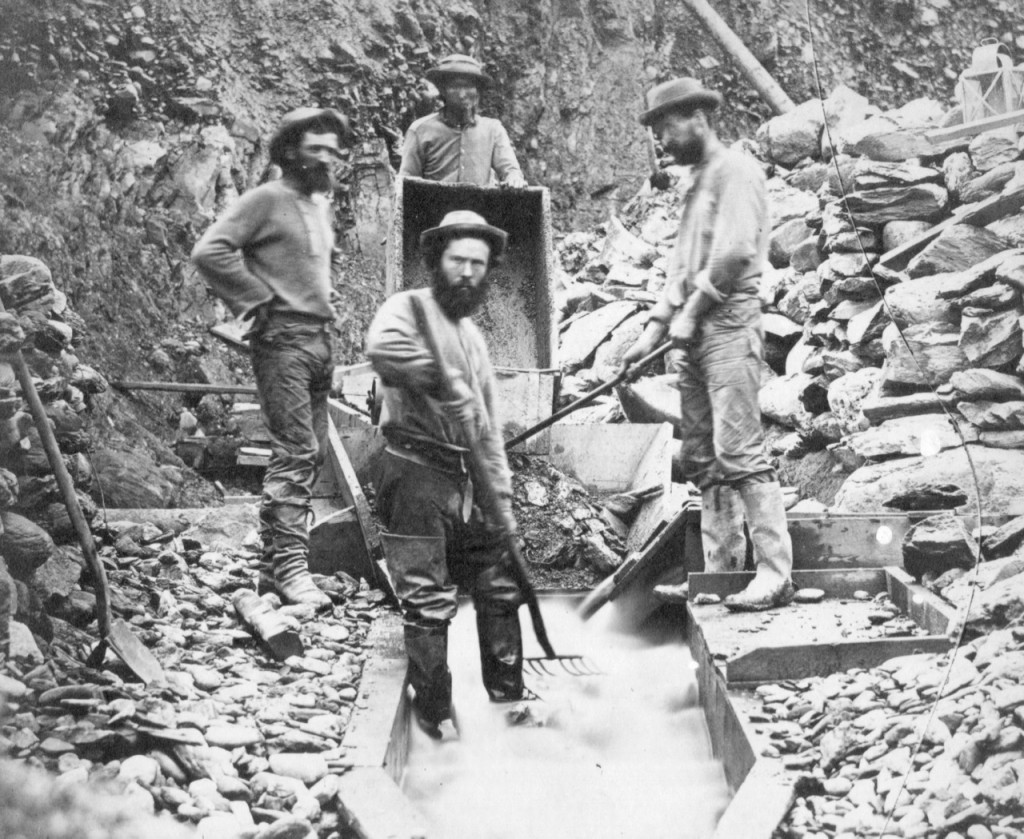

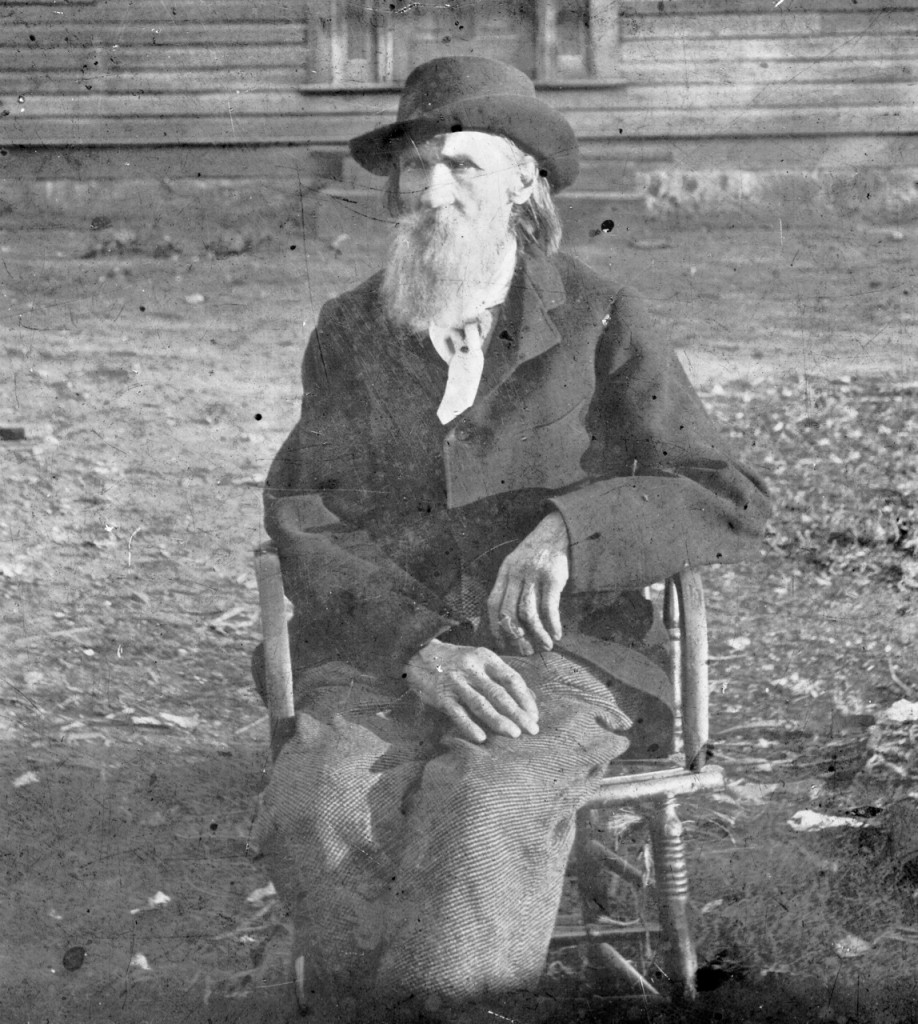

Whitfield Chase. Photo courtesy of the Chase and District Museum and Archives

In 1862, Alexander Fortune joined the “Overlander Party” to travel over land to the Cariboo gold fields. His lack of success prompted him to try his luck in the Big Bend, where he was flooded out. While attempting to find gold in the Shuswap in 1866, he paddled up what was then called the Spallumcheen River where he found natural meadowland and remarked, “Thank God…. this is better than gold!” The following year, he returned with seeds and tools and began homesteading. Within a few years, Fortune along with other settlers achieved great success with their agricultural efforts thanks in part to the willingness of the Splatsin people to work for them.

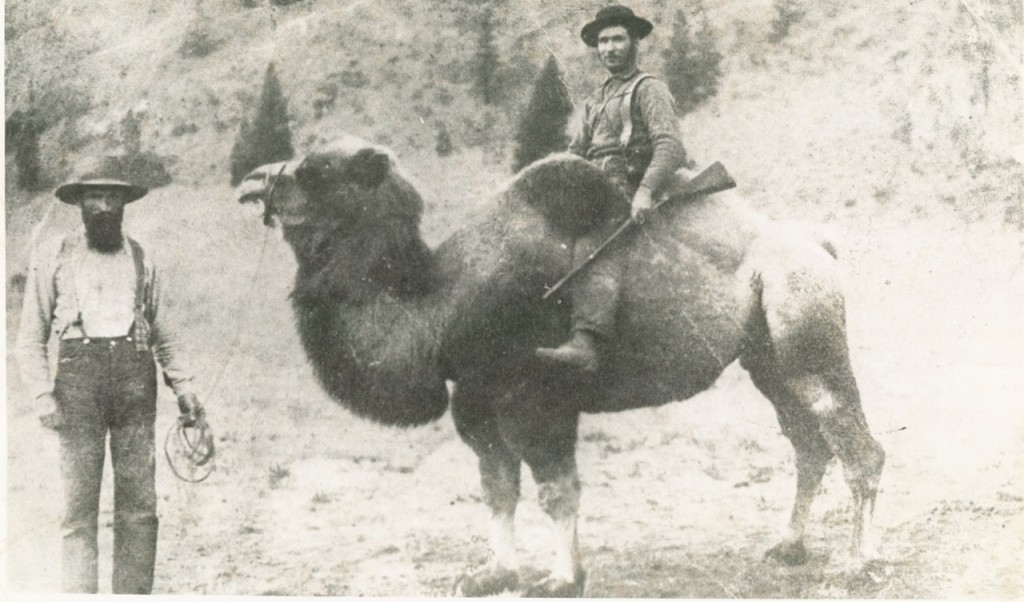

One of Ingram’s camels. Photo courtesy of the Kamloops Museum and Archives

According to pre-emption records, settlement began in the natural grasslands of Grande Prairie (now Westwold) in 1864, when three men applied for land in the middle of the valley. The following year, Henry Ingram acquired the rights for this land. He brought with him the infamous camels that had been used unsuccessfully as pack animals on the Cariboo Road. Soon, more settlers arrived, and descendants of some of these families still reside in the valley today.

Alexander Fortune. Photo courtesy of the Enderby & District Museum and Archives

The only other Shuswap settlement hub in 1867 was in the White Valley near where Lumby is today. Early settlers were first attracted to the area because of the mining activity at Cherry Creek. Louie Christien and his friend William Peon discovered gold there in 1862 and within two years there were three companies of men working at the creek.

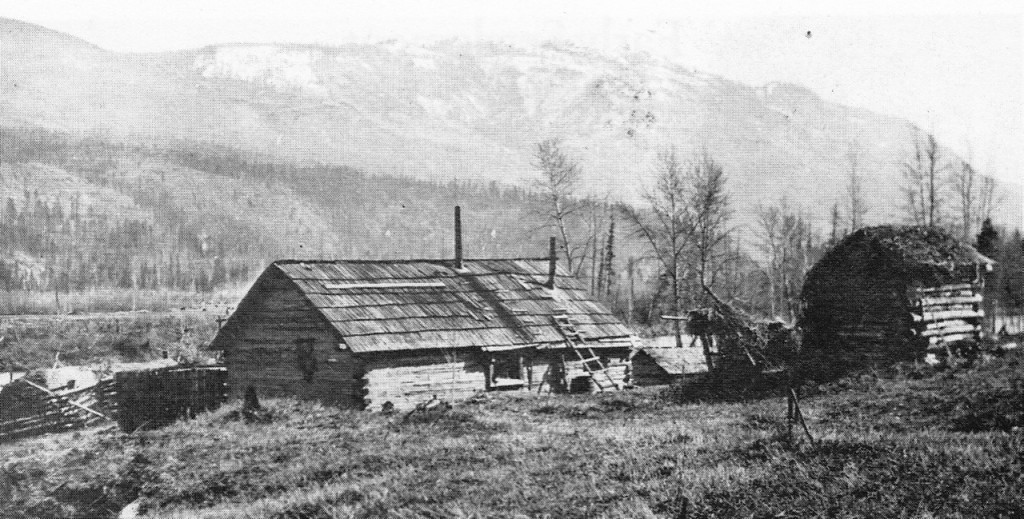

Homestead cabin on the Shuswap River, circa 1898. Photo courtesy of the Enderby & District Museum and Archives

The Shuswap region was still mostly pristine forestland 150 years ago. Most of the miners had come and gone, while a few remained to seek out their fortunes homesteaders. Angered over the loss of their lands, the Secwepemc people offered some resistance, but many soon found work helping the settlers clear the land and harvest the crops. It would take a few decades more and the building of the railway before the landscape began to change dramatically as the forests were logged, more land was cleared and communities developed.

POSTSCRIPT

Quotes from 1867:

On August 29, 1867, Mr. H.P. Featherstone reported about Seymour City: this once flourishing village is fast going to decay. There were twenty-four inhabitants left including eight stragglers, two Indians and six wholesale merchants. Out of thirty cabins, fifteen are empty. (From Seymour Arm, Historical Gem of the Shuswap, by Gwen Bauer and Estelle Noakes).

from Abercrombie’s history of Sicamous:

The Honourable Joseph W. Trutch, Chief Commis- sioner of Lands and Works, was consulted by Roderick Finlayson on December 10, 1866, and again on April 13, 1867, by mail on the subject of lands acquired by the Hud- son’s Bay Company at Savona’s Ferry and at Seymour. He transmitted the original certificates of sale for Town lots, No. 5 and No. 6 in Block 10 at Seymour, two dated June 9, 1866, for $50. each, certified by Mr. Hewes; and two dated September 19, 1866, for the same price, certified by the Hon. P. 0. Reilly. The usual registration fee of $2.50 was forwarded.

At the same time Finlayson requested the Title Deeds for the above lots and also for the Company’s Reserve at Seymour and at Savona’s Ferry.

The Hudson’s Bay Chief Factor, W. F. Tolmie, men- tioned, May 9, 1867, to the Colonial Secretary, the Hon. Arthur N. Birch, that the Steamer “Marten” was operated with a $400. subsidy from the Government for each month in the current year she might run.

Nevertheless, by June 12, 1867, Finlayson reported to Moffat at the Kamloop’s Post, that the “Marten” in need of repairs had been tied up at Kamloop’s Lake awaiting repairs to the machinery and required further caulking to the hull. The H.B.C. at this time expressed doubt as to whether she would run in the coming season as business was so poor.

At that time Bissett was asked to proceed to French Creek by way of Savona’s Ferry and Seymour Arm to enter fully into the affairs of that Post.

Finlayson then advised Moffat that Bissett would ex- plore the Eagle Pass and report to them the possibility of opening a trail through it to the Columbia River. Also ad- vice was given to secure the services of Baplisteon, or an other individual who had previously accompanied McKay, to escort Bissett.

Later, soon after Bissett had been instructed to explore and examine the possibility of building a pack trail through Eagle Pass at an easy grade to the Columbia River, June 20, 1867, Finlayson assessed the cost of cutting a road through that pass for pack animals. It was of great impor- tance, in order to utilize the Steamer “Marten” then on the Lake to get an outlet to the Columbia River for the Lake traffic from the Shuswap. He pointed out that there was a River leading in the direction of Cherry Creek. He advis- ed Bissett to examine it to see how far it was navigable and to estimate the distance from the rich Cherry Creek Silver Mines. The thought was that a trade might be opened in that direction. Likewise, he wanted ascertained how far the Eagle River was navigable for the “Marten” and the distance from that point to the Columbia River.

He sent Bissett on this mission with confidence in him since he had the aid of the reports of Eagle Pass already given him by the Government Assistant Surveyor and also had maps of the locality handed to him.

Mr. Sabiston managed the Hudson’s Bay Company Store at Seymour Arm from 1865 to 1867, when he was ordered to close it.

Moses Lumby, promoter of the Shuswap and Okanagan Railway and an Okanagan settler in 1870, was the Big Bend mail conductor, 1866-1870.