Although the Egyptians were the earliest people to glue thin layers of wood together, plywood as we know it today was first manufactured in France in the 1860s using veneers cut from logs with a rotary lathe that had been invented a decade earlier in Sweden. Plywood gets its strength from the perpendicular layers of veneers, thus making it a versatile building material. Some of Canada’s finest plywood is made from Shuswap timber in Canoe, where Gorman Bros. now operates the plant that Federated Cooperatives first opened in 1965.

Recently, I was fortunate to get a tour of the Canoe plywood plant and learn about the advanced technology used in the manufacturing process. Since Gorman’s purchased the mill and forest licence in 2012, they have invested over $50 million to modernize the operation, which resulted in a vast increase in efficiency and nearly doubled the production.

Our tour began at the “green end,” where the 8-foot 6-inch-long logs arrive after being soaked in a hot water vat for 6 to 7 hours. Here, the high-speed lathe slices off the eighth-inch thick veneer in just 6 to 8 seconds, depending on the size of the logs, which can be from 6 to 28 inches in diameter. As the veneer moves quickly along the line, it is cut with a long knife into 4-foot 6-inch-wide sections.

This machine measures the moisture content of each sheet to determine if it is heartwood, light sapwood, or heavy sapwood, which is found on the outside of the log. Sapwood veneer that is relatively clear wood is sent through a robotic machine that cuts out the knots and inserts a patch. The piles of veneer are then sent to the driers, where the amount of time each sheet takes to move through is set by the moisture content of the sheets.

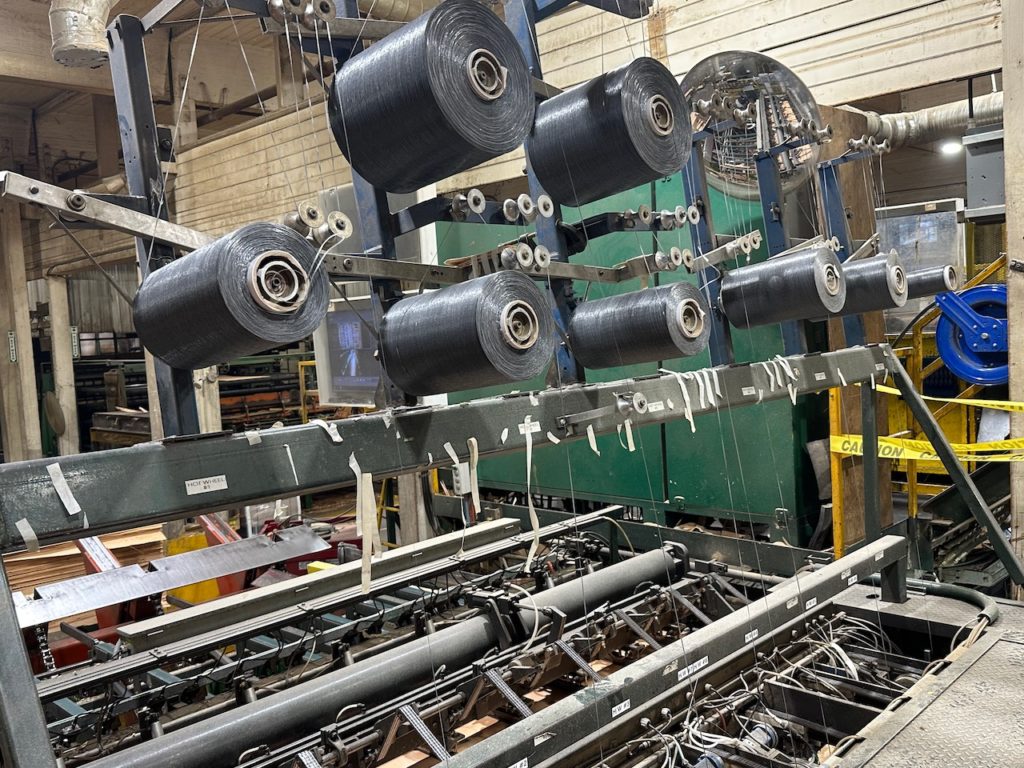

The next step in the process was most fascinating. To make the inside filler layers out of the softer heartwood, each sheet is cut into 4.5-foot-long sections, which are then rotated and joined together with glass fibre that is pressed into the wood. Resin glue is applied from the next machine as the veneer sheets pass under it, are sandwiched together and then piled into stacks, which are initially compacted under 2,000 pounds of pressure.

These stacks are moved to a machine operated by one worker who moves up and down on a lift as he pushes each sheet into a hot press that again uses 2,000 pounds of pressure for the final compaction. Then each plywood sheet is trimmed and graded, and the highest quality plywood is sent through another robotic machine that fills the knot patches with putty. Each stack of plywood is then stenciled with the Canoe brand name and then another robotic machine prints the size and grade of the wood.

Over two hundred employees work in three shifts to produce the quality plywood, including 17 millwrights and 8 computer programmers who keep the maze of machinery and robotics operating smoothly. Safety is number one at Canoe, and as a result the plant is one of the safest in the province. It is also one of the most productive, efficient and pollution free operations.

In addition to renovating the green end that boosted recovery and production, which increased from 150,000 to 260,000 cubic metres, they will be purchasing a new veneer drying line, new vats, and automation systems. Most importantly, Gorman’s cleaned up the airshed by adding a Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer that heats and re-burns the emissions, which has reduced up to 90% reduction of emissions from the site, much to the delight of the nearby residents.

When Gorman’s purchased the plywood plant, they also took over the woodlands, which includes several forest tenures including a tree farm licence. The Shuswap forests are diverse, which fits well with the other divisions in the Gorman group. Most the Canoe plywood is made from Douglas fir. Other species, including cedar, spruce, hemlock, and balsam flow to the Downie sawmill in Revelstoke or to the Gorman Bros. mill in Kelowna. After many decades of logging and recent forest fires, the timber supply is not what it once was, but nonetheless, it still provides a large proportion of the 22 truckloads needed per day to supply the Canoe plant.

Gorman’s has plans for more improvements in the future, including automating the machine that feeds the second press. As well, they are looking into more value-added systems, including producing plywood sheets up to 20 feet long, as well as fire-resistant sheets and concrete forms that have a sheet of resin on the surface. The Shuswap is fortunate to have such a well-run plywood plant that produces quality building material used for construction primarily in Canada, with just three percent shipped to the United States.

POSTSCRIPT

There are three types of veneer that come off each log. heartwood from the centre, light sap wood and heavy sap wood from the outside of the log, and since each type has a different moisture content, each spend a different amount of time in the dryer. The heartwood ends up in the centre of the panel, and the sap wood is on the outside. Only 15 percents of the panels are graded to be select and only 5 percent is supreme and better. The rest is plain sheeting, with 7 percent D-grade. Most of the plywood is made from Douglas fir, with just 15 percent spruce. The hemlock logs are sent to the Downie sawmill in Revelstoke.

What little waste is left, is chipped and sent to the pulp mill inKamloops. The cores are either sent to a re-manufacturing facility to be cut into 2x3s or smaller or they get used as fence posts.

When asked about how the plantations are doing, given that many were planted with Lodgepole pine, Luke Goebbels, a company forester, explained how many of the lodgepole died and were replaced naturally with fir and cedar. I have noticed this too, as it is not easy to find a Lodgepole pine in many plantations where they were once thick.

Manufacturing plywood mades good use of the timber available, with minimal waste produced, compared to sawmills that produce so much sawdust compared to a knife slicing veneer that makes none.

More photos:

The robotic machine that cuts and fills the knot holes, photo by Jim Cooperman