Prior to European contact, the Secwepemc people had their own spiritual beliefs and customs based on respect for all life and nature, that had developed over many thousands of years. But after just four decades of life with the fur traders, the Secwepemc were eager to embrace the White man’s religion, but in their own ways. The first opportunity came in February 1843 when 400 natives gathered to wait ten days in the cold outside the Thompson’s River Post for a visit by Jesuit Father Demers.

It was not until 1867, that missionaries established their first log-cabin church on the reserve in Kamloops, which was soon followed by the construction of early churches elsewhere, including at the Adams Lake and Neskonlith villages. These missionaries were Oblate Catholic Priests who came here directly from France as part of their worldwide mission to convert the poor peoples of the world to Christianity, as “soldiers of the Pope.” Their arrival coincided with the recent decimation of so many natives from smallpox, which Secwepemc spiritual healers had no ability to control.

According to the ethnographer James Teit, the Secwepemc had a forewarning about the missionaries, as he recorded a story in his 1909 study of the Shuswap. Prior to first contact, a half-breed who was visiting from Hudson’s Bay warned the people “strange men would come among them, wearing black robes.” He advised them “not to listen to these men, for although they were possessed of much magic, and did some good, still they did more evil.” He also explained how these men were descendants of the Coyote, and like him “were also very foolish, and told many lies.” Unfortunately, the Secwepemc did not heed this warning, but may have used this knowledge to avoid fully accepting or believing the teachings of the Oblate missionaries.

The first step for the missionaries was to perform baptisms that included providing each native with a Christian name selected from a list of French baptismal names. Initially, the natives considered these new names to be an addition to their Secwepemc names. However, eventually their original names ceased to be part of the public, written record and their Christian first names were passed to their children and became last names (e.g. Jules, Manuel, Antoine, Thomas and Abel).

The Oblate missionaries travelled far and wide to every native village to perform baptisms, provide new names and attempt to convert the people to Christianity. One reason for their success was their willingness to use the Chinook Jargon, which was translated into Secwepemc by local, bilingual interpreters. Often the meanings were lost in the translation. Another reason was that the Secwepemc had a strong sense of right and wrong similar to the Christian teachings.

Interestingly, because the Secwepemc heard these teachings in their own language, Secwepemctsin, they associated the meanings to their existing belief system. For example the concept of sin was associated with their belief in the social responsibilities they have towards each other, rather than the Christian fear of god. However, since the concept of hell had no parallel in Secwepemc spirituality, it was difficult for the natives to accept what was deemed to be the consequence of the non-Christian way of life.

By the 1870s, the Secwepemc were protesting the grossly unfair reserve system and they received some support from Father C.J. Grandidier of the Okanagan Mission. He wrote at length to the government about the escalating problems, “their reservations have been repeatedly cut off for the benefit of the whites, and best and most useful part of them taken away, till some tribes are corralled in a small piece of land…” With additional support from the Indian Superintendent, the government relented and appointed the Sproat Commission, which recommended improvements that were never implemented.

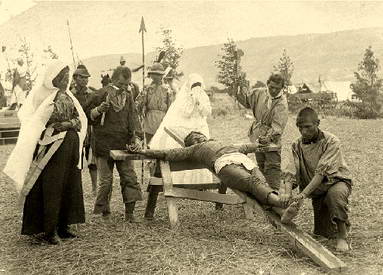

In 1891, Father Le Jeune arrived in Kamloops and quickly learned the Secwepemc language in addition to seven other indigenous languages. He then set out to translate prayers, hymns, liturgy, and parts of the Bible into Secwepemctsin. He also published the Kamloops WaWa, a newspaper published with shorthand adopted for the Chinook Jargon that contained primarily religious teachings and some general news and had up to 2,000 subscribers. His work was well respected and appreciated by the Secwepemc people, especially the well-attended Passion Plays he produced with a large cast of natives.

Le Jeune also wrote letters to support the Chief’s efforts to enlarge their reserves and in 1904, he accompanied Kamloops Chief Louis on a trip to France and Rome, where they had an audience with the Pope. The relationship between the natives and the Church slowly began to change in 1876, when the federal government assumed the responsibility for educating Indian children. The first school on the Kamloops reserve was built in 1890 and three years later the Oblates took it over and thus the disgraceful effort to annihilate First Nation culture began and continued up until 1977.