The familiar adage, ‘the only thing constant is change’ certainly applies this year to the Adams River. For many visitors the question was, “where are all the salmon?” as viewing opportunities were limited because the river changed course, and the channel that runs by the new viewing platform was reduced in flow so that only dozens of fish could be seen. Overall, despite earlier predictions of millions, the final number could be lower than the 707,000 that returned in the 2014 brood year.

Water flow in the channel at the viewing platform has been reduced to a trickle

Water flow in the channel at the viewing platform has been reduced to a trickle

Many rivers and streams naturally meander, but significant changes usually occur over hundreds or thousands of years. It is possible that the rapidly changing climate is accelerating the movement of the Adams River, as higher snowpacks and warmer spring temperatures lead to increased flows and channel shifting. In the last eight years the river first moved north, destroying the old viewing platform and parts of the riverside trail and then to the south, leaving the viewing area high and dry.

It boggles the mind how so many experts could be involved in the decision to spend many thousands of dollars on a new viewing platform, when the river is prone to change course. Another waste of money was the Cottonwood coho groundwater spawning channel, where access for salmon is now blocked by a beaver dam that cannot be removed because it is in a park.

While salmon face many threats, including from fish farms, warming ocean waters, and competition from Alaskan hatchery fish, the major factor that determines how many sockeye return to the Adams is the fishing quota. An international organization, the Pacific Salmon Commission, determines the quotas and openings each year based on the recommendations from the five panels that represent each region.

While salmon face many threats, including from fish farms, warming ocean waters, and competition from Alaskan hatchery fish, the major factor that determines how many sockeye return to the Adams is the fishing quota. An international organization, the Pacific Salmon Commission, determines the quotas and openings each year based on the recommendations from the five panels that represent each region.

The work of the Commission dates back to the 1920s, when overfishing and river degradation and obstruction resulted in competition and conflicts between American and Canadian fisheries. Government meetings in the 1930s led to the formation of the Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission in 1937, which focused on conservation efforts, including building fish ladders and spillways at Hell’s Gate and blasting away the splash dams on the Quesnel and Adams Rivers.

The work of the Commission dates back to the 1920s, when overfishing and river degradation and obstruction resulted in competition and conflicts between American and Canadian fisheries. Government meetings in the 1930s led to the formation of the Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission in 1937, which focused on conservation efforts, including building fish ladders and spillways at Hell’s Gate and blasting away the splash dams on the Quesnel and Adams Rivers.

After a comprehensive treaty was signed in 1985, the current Commission was created to replace the first one. Test fisheries are conducted to estimate the size of the runs and the information is provided to the panels in order for them to recommend the allowable catch. While the Commission is guided by science, the final decision is ultimately a political one that is influenced by the economic demands of the fishing industry.

After a comprehensive treaty was signed in 1985, the current Commission was created to replace the first one. Test fisheries are conducted to estimate the size of the runs and the information is provided to the panels in order for them to recommend the allowable catch. While the Commission is guided by science, the final decision is ultimately a political one that is influenced by the economic demands of the fishing industry.

In August, the test fisheries provided a rather unrealistic high estimate of nearly 7-million fish returning to the Shuswap, which resulted in a catch of 2.5 million fish. The size of the run was downgraded after the fish in the ocean were caught, with the latest estimate for the Adams in the range of 675,000 returning salmon. Critics point out that the estimation techniques are highly unreliable and although the focus is supposed to be on conservation, the decision-making is slanted to benefit the fishing industry.

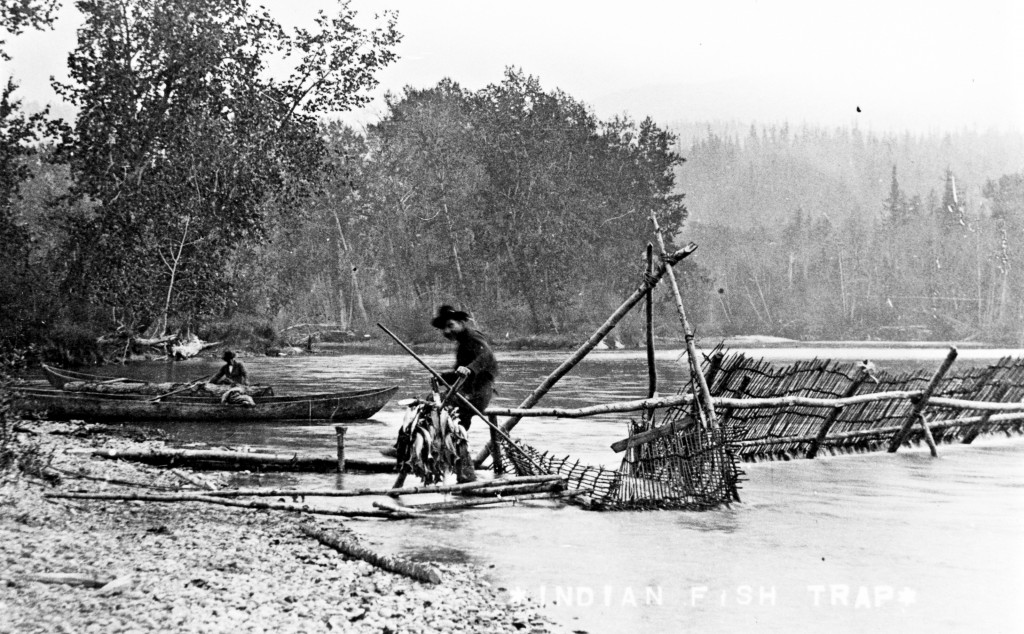

Fish weir on the Shuswap River in 1891, photo courtesy of Enderby & District Museum and Archives

Fish weir on the Shuswap River in 1891, photo courtesy of Enderby & District Museum and Archives

One solution would be to switch to the same type of sustainable fishery practices used by First Nations for thousands of years. Terminal fisheries can be designed to allow harvesting only after a surplus has been confirmed, thus leaving enough salmon to spawn to allow for the stocking levels to increase instead of decrease as is currently happening. As well, smaller runs can be protected, which is not occurring now with indiscriminate ocean gillnetting.

Salmon in the lake – photo by Dale Anderson, Ocean Pacific Water Sports

Salmon in the lake – photo by Dale Anderson, Ocean Pacific Water Sports

Another change with this year’s run is that it was late. There were still large schools of fish holding in the lake last week and it was not until recently that the spawners began to die in larger numbers. One concern is that some of these late arrivals may have passed the point of being able to spawn, given that some fish caught in Savona had egg sacks ready to release.

The final count will not be available until next February, at which time we will finally learn how well the salmon are being managed. We will also find out if the Adams River is losing its reputation as the richest spawning river in the Province, as four years ago 300,000 more sockeye returned to the Shuswap River than the Adams.

The final count will not be available until next February, at which time we will finally learn how well the salmon are being managed. We will also find out if the Adams River is losing its reputation as the richest spawning river in the Province, as four years ago 300,000 more sockeye returned to the Shuswap River than the Adams.

POSTSCRIPT

Here is how fisheries expert and critic Greg Taylor describe the allotment process:

“How it works is the Fraser Panel makes an educated guess as to the run size of a particular stock grouping. In this case, late-summer sockeye. Canada gets its share, the US its share. DFO then allocates the Canadian commercial share (after deducting for FSC, Recreational, and test fishing) between the seine, gillnet, and troll sectors. The Area B seine is a ITQ fishery so each of the 168 Area B seine licences gets 1/168th of the seine allocation. The Savona fishery has been allocated a number of Area B seine licences. So the Savona fisheries quota is the same as any other Area B fishery (less a stock adjustment).”

When asked if terminal fisheries (also called “direct-catch” fisheries by Greg Taylor) should replace the current mixed-stock fisheries, Pacific Salmon Commission biologist Mike Lapointe replied that it would be difficult to swithc because there is a lack of the infrastructure that would be needed to harvest enough salmon needed to supply commercial needs. DFO biologist Keri Benner explained that the quality of salmon caught closer to spawning ground would less that adequate, although the salmon caught in Savona by Riverfresh is quite good.

The best example of a successful terminal fishery is at the Skeena River, where 2/3 of the catch this year was known stock. Here is a video about this fishery – Skeena terminal fishery.

fish spawning near the mouth attracting a photographer’s attention

fish spawning near the mouth attracting a photographer’s attention