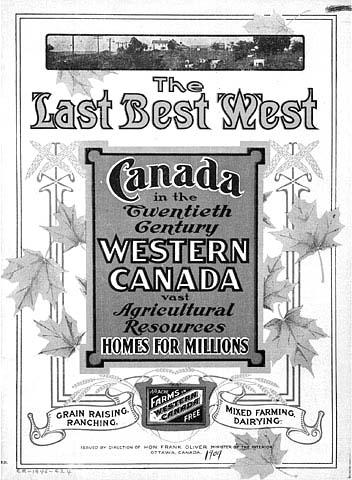

Prior to 1896, there were few permanent settlers in the Shuswap. Other than the early-formed settlements in Chase, Westwold (Grande Prairie), Fortune’s Landing (Enderby) and Sicamous, most of the Shuswap was still vacant land except for the small Indian reserves. With the election of Canadian Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier, a settlement campaign began called the “the last Best West,” named because by then most of the best land in the U.S. had already been settled. This campaign led to first a trickle and then a flood of settlers moving to the Shuswap.

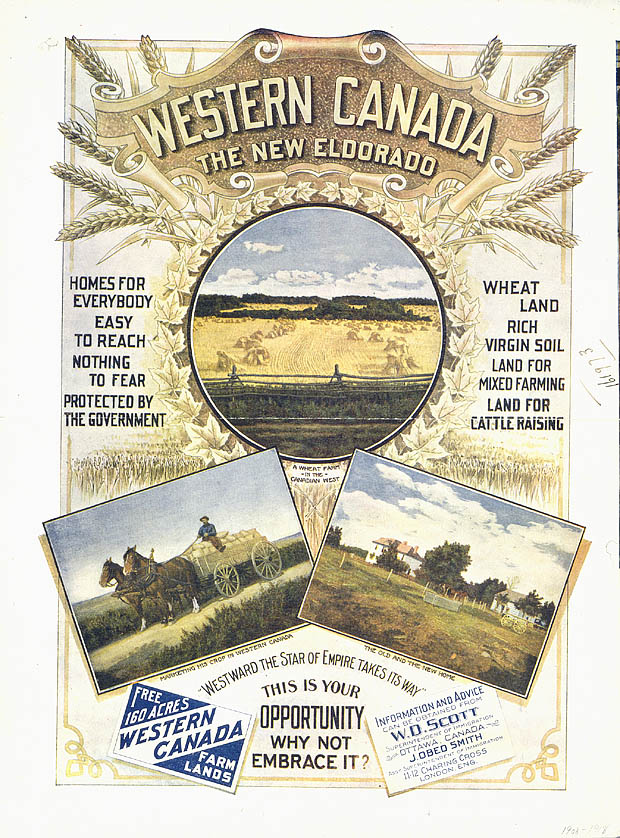

From 1896 until 1905, Canadian immigration was under the responsibility of Clifford Sifton, who was the Minister of the Interior. Sifton instituted a massive program to encourage settlement through the establishment of immigration offices throughout Europe and the United States. Many different forms of advertising were used, including newspaper ads, brochures and posters that portrayed Canada as a prosperous nation with rich farmland in need of farmers. The benefits of moving to Canada were touted at agricultural fairs and at schools and journalists were given free tours to write about.

Sifton also offered attractive incentives including in some cases, free passage to Canada, free supplies to new immigrants, and most importantly, up to 160 acres of free farmland. Immigration agents were taken off their salaries and were required to work for commissions and steamship companies were offered bonuses for each new immigrant. Pamphlets, filled with glowing descriptions of the railway, bountiful amounts of arable land and the scenery were printed in dozens of languages and distributed throughout Europe. However, negative information was omitted, such as the cold Canadian winters and the difficulties encountered in clearing land.

Given the prejudices of the times, the campaign focused on enticing immigrants from either the United States or Europe, while blacks and Orientals were discouraged from coming. Sifton was primarily interested in developing agriculture in the west, so most of the efforts went to attracting immigrants from rural Britain, Germany, as well as Eastern European and Scandinavian countries. To facilitate homesteading, Sifton increased the surveying of the western lands and he pressured the railway companies to free up their land grant properties to make these available.

A number of other factors contributed to a huge wave of immigration. Most importantly, was the enlarging international market for agricultural goods, particularly hard wheat and other grains. Many Europeans were suffering from hardships due to a troubling economy, industrial pollution, high unemployment and in Ireland, the potato famine. Canada offered the chance for a better life, for both the lower classes who had limited options for the future and even for the wealthy who were attracted to the opportunities for investing in new businesses.

Sifton’s program was an enormous success as over one million immigrants came to Canada between 1896 and 1905, with approximately 50 percent settling in rural areas. Within a decade, the population of the west increased from 300,000 to 1.5 million. This immigration boom changed the face of the Shuswap, as settlements and farms became established in the North and South Shuswap, Salmon Arm, Malakwa and throughout the Shuswap River valley. Most of these new settlers were either from the United States, Great Britain, and Scotland as Eastern Europeans primarily settled in the prairies. A few communities, including White Lake and Malakwa attracted settlers from the Scandinavian countries.

The Shuswap was particularly attractive to younger British men from upper or middle class families, who were not the first born and thus unlikely to inherit the family property or business. Some of these immigrants were called “remittance men” because they received a regular stipend from their families. In some cases, these men were also the “black sheep” of their family because of their drinking problems or other lifestyle habits.

My fascination with local history stems in part to the parallels between the lives of the early settlers and my own early days in the Shuswap spent carving a “homestead” out of the bush without power or running water. As I fled a nation obsessed with an unjust war to live off the land, so too did many of the pioneers leave their problem plagued countries and endured hardships to build their homesteads with similar goals of self-reliance and healthy living. And just as the Canadian government promoted immigration to settle the west well over 100 years ago, so too did Canada foster the entry of adventurous war resisters some 40 plus years ago.

POSTSCRIPT

For each of the first settler families there is a unique story about how they decided to settle in the Shuswap. The vast majority of these settlers came from England and it many cases, these adventurous homesteaders knew each other. Some were friends or members of the same extended family. Others gained new friendships during their journey to western Canada. News about the Shuswap traveled quickly and many of these settlers heard about the advantages of the Shuswap as they were heading west, either on the train or at the train station, as this was the primary mode of transportation.

All of these early settlers had the same dream of building a homestead where they could grow their own food and somehow sell their surplus produce and meat. They faced enormous challenges, from clearing land covered in enormous trees to building homes that could keep them warm during the cold winters that were common then. And as important to them as planting fruit trees and cutting firewood, was the rich social life they managed to create with such minimal facilities. They made their own music, built their own schools that doubled as community halls where they danced and partied sometimes until dawn.

I am always amazed at how quickly they could build their homes and barns, with just hand tools and hard work. Key to their success was cooperation, as families helped each other build their homesteads and they shared their knowledge. their tools and their dreams.

One of their major obstacles was access, as the lack of roads meant transportation was difficult. For those who settled near the lakes, boats were their main way to access their homesteads and move goods and supplies. During the winter, they were able to use their horses and sleighs to travel on the thick ice that formed nearly every year. However, during the early and late winter, there were many cases when there were accidents or near accidents when thin ice gave way.

It was an incredible era and there is much to be gained from learning more about these courageous people who chose to carve a life out of the Shuswap wilderness.