In the early 1970s, Norbert Maertens, a computer engineer from Belgium, travelled the world for business and developed an interest in intentional, ecologically based communities. He became an advocate and gave talks about environmental issues and eco-friendly lifestyles throughout Europe, using giant paper scrolls (left over from computer plotters) for a visual aid, and thus earned the nickname, “scrollen apostle.” His message was based on the “back-to-the-land” vision of those times, that a change in lifestyle based on harmony with nature was needed in order for humanity to live sustainably on our planet.

As more people became inspired by the vision, a small collective formed known as the Genesis Community. When their hobby farm in Belgium used as a gathering center became too small, some moved to the south of France, where they found the area’s rural traditions were incompatible with their New Age aspirations. Consequently, they looked for a more progressive country and only the Canadian embassy responded in due time.

After receiving visa approval to set up in Canada, the next step was deciding where to settle. Using the I-Ching as a medium for divination, the answers to their questions indicated they were to move to a western “city of fruit.” A pendulum was used to find the exact point and it stopped over the small Shuswap community with the apropos name, Cherryville.

In 1978, Norbert along with an initial group of communards mostly from Belgium, arrived in Vernon where they camped at Kalamalka Lake. While purchasing supplies at the local natural foods store, Sunseed, they met Robin LeDrew, who invited the entire crew to live at the Alternate Community near Lumby, which had recently been vacated by the previous group of back-to-the-landers.

It did not take long for them to realize that for their sizable group, they needed their own large parcel of land. A chance encounter with a farmer named Bud Lucas, who was fixing his truck in the parking lot of the Cherryville Community Centre, resulted in the group purchasing his 185-acres known as the Workshare Farm. Coincidently, Bud had been living in a U.S. commune that supported itself by making hammocks, which Norbert had visited during his tour of U.S. intentional communities.

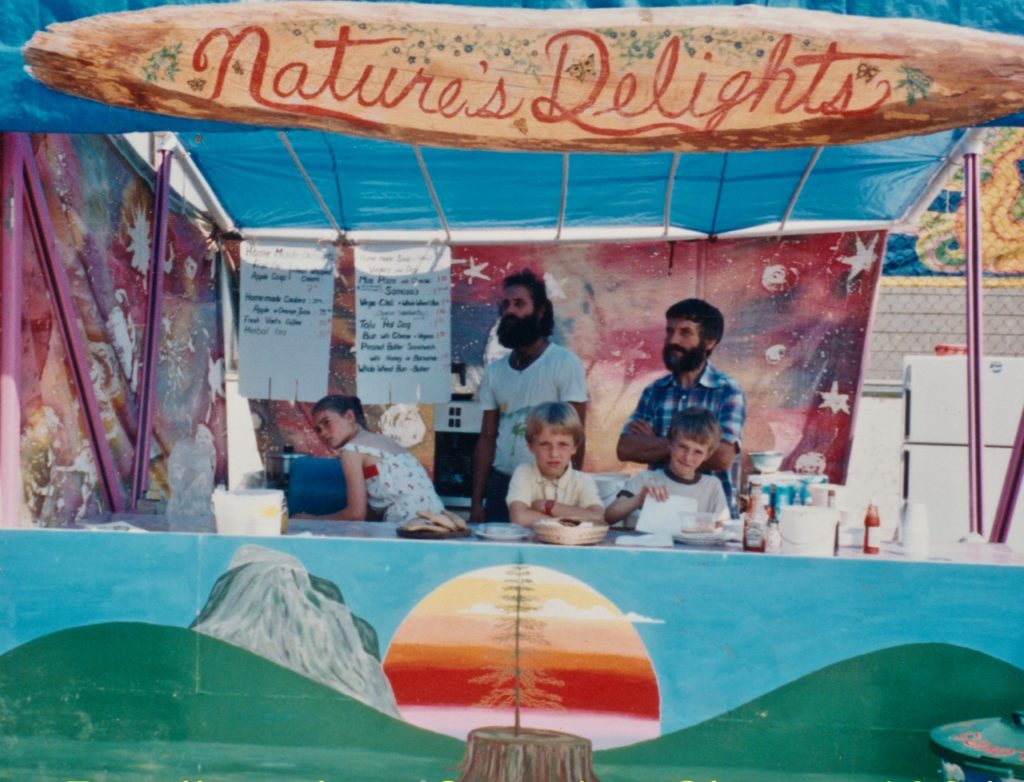

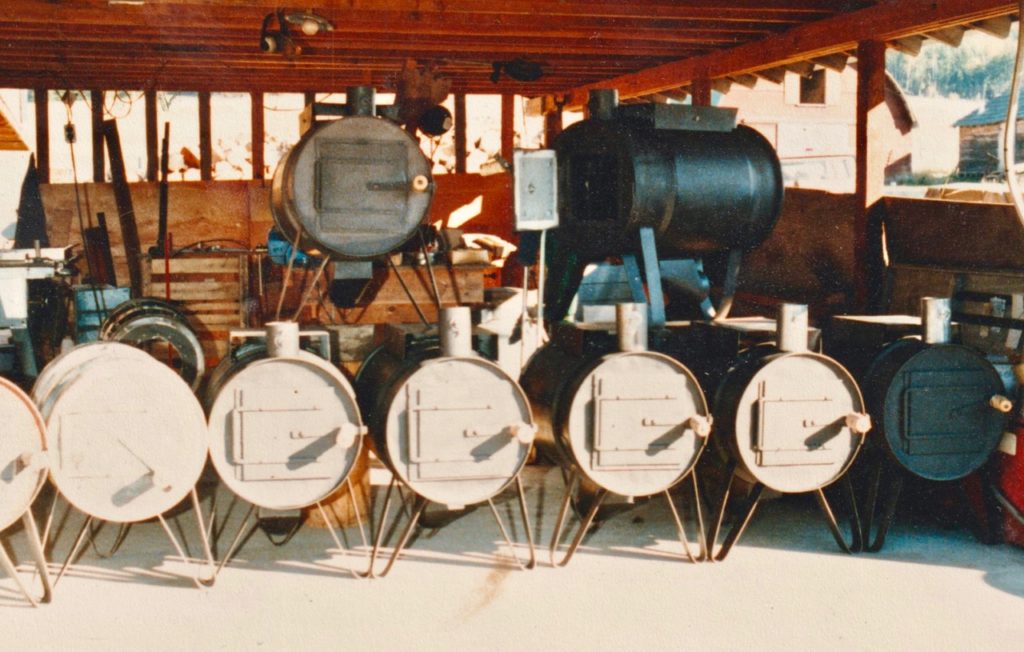

During the time the Workshare Farm transitioned into the Genesis Community, Bud stayed on for several months and helped to resurrect their hammock industry to help the new community prosper, which for a time made Cherryville the “Hammock capital of Canada.” To provide additional income the group made barrel wood stoves and solar food dryers, grew alfalfa sprouts and greens for the local stores and made tofu and tempeh.

As more community members came from Europe, the building restrictions on designated ALR land became an obstacle, and they searched to find a larger, more remote location. Eventually, Bear Valley, a secluded property at the end of a public road between Lumby and Cherryville, surrounded by forested Crown land and away from it all, was purchased and renamed the “Hailos Community.” The 640-acre valley, with large fields, fertile garden areas and a small lake offered the perfect place to live sustainably, in harmony with nature.

The remote location was a major challenge for the Europeans who lived there without hydro and phones while enduring long winters and language and cultural barriers. Many faced emigration problems and had to return to their country of origin. As more Canadians came on board, the community persisted and more buildings were constructed, including a geodesic dome and an octagonal log building to serve as a community center. Despite their isolation, Hailos engaged in various outreach programs, offering classes and workshops in Bear Valley and organized the 1985-87 Spring Festivals of Awareness in Vernon.

After eight years, members began to lose interest in community living and drifted away, which resulted in lack of maintenance to the buildings. Eventually the land was sold and today, Bear Valley is an artist retreat centre. Norbert moved to Lavington, where he continues to live close to nature based on voluntary simplicity, while remaining active in various environmental organizations and movements.

POSTSCRIPT

The Hailos Logo with the Camel’s Hump in the background.

This logo was the cover page for a pamphlet that was provided to visitors and interested participants at Hailos events both at Bear Valley and in Vernon. One goal for the community was to link it with similar groups throughout North America via a “Rainbow Connection.” Visitors were limited and prior notice was requested. If visitors wished to stay longer than one day they were expected to contribute their “time, labour or skills” to the group’s community projects. Campers were welcome for $2 per night and $10 per week, with accommodations available for $25 per week.

The pamphlet explained how there was room in the community for people “who share a similar vision for free spirited brothers and sisters, who have come to accept and understand that ‘love is work in action’ and that if we live our beliefs, we can turn the world around.” Those interested were asked to explain “what aspect of Hailos you feel most attuned to and what aspects you dislike, what skills and experiences are are able to share with use, the ages of your family group and the spiritual and social disciplines that have shaped your life.” Their name Hailos came from ancient Indo-European root “kailo” which also resulted in the words, hole, holy, whole and wholistic.

Upon receipt of the requested information, those interested would receive a copy of the Hailos constitution and the shareholders Agreement for $5. Prospective members were invited to visit for an extended period while they would live and work with the community. Full memberships were granted for those who completed a one-year provisional membership and who agreed with the constitution. The shareholders agreement specified how members were expected to purchase a minimum of 200 shares at $50 each (two shares per month), which were non-refundable and non-transferable. A minimum of 24 shares had to be purchased before a member could build a home. Other fees included $20/month for land maintenance and taxes. Members who used the land or amenities to run a business were expected to tithe 10% of their net income. In addition to the financial requirements, members were asked to contribute two hours of labour per week to community projects.

The community accepted the “universality of all religions” and recognized and supported freedom of spiritual pursuits. Their goal was to pursue a lifestyle intended to contribute toward a “more peaceful world” by living “in harmony with nature and with the order of the universe.” It was both a community and a healing centre committed to “creating an environment in which self-healing and personal growth can flourish.” The community respected the need for individual and family privacy and allowed members to be responsible for their own homes and personal needs. There were two entities, the registered, non-profit society under which the community was organized and the limited company that was owned and operated by community members. The community was primarily vegetarian and drugs and alcohol were discouraged. The land was owned by all the members who were shareholders and decisions were made during the many meetings. Consensus was the goal, but when it was not achievable, votes needed to be carried by a 75% majority. There were the traditional positions of president, secretary and treasurer, plus a spiritual director.

Despite all their good intentions, it was difficult to maintain the group’s dedication to the idealistic goals and as the original members began to return to their home countries, those that replaced them did not carry on with the original intentions of the group. When the financial obligations were not followed and drugs and alcohol became more prevalent, the community could no longer continue. Nonetheless, years later Norbert still believes strongly that the world needs communities like Hailos. He began writing a treatise on the topic of community back in 1972 called “Proposal for Intentional Community,” which has continued to evolve since then. He writes, “Our only alternative is the self-governing of small groups of people, groups with a common purpose and common resources, governed with a common over-arching motivation which is as benign and as close as possible to those affected…” He sees returning to true community living as the best way to reverse the current slide toward the planetary tipping point of “no return.”

The Coalition of Cooperative Communities newsletter (CICC – see the previous blog) included an update from the Workshare Farm a few years prior to when the Genesis Community purchased it. It produced both hammocks and wood heaters. New members had to contribute $2,000 each, for which they received vegetarian meals and shelter, plus $3 per week for a clothing allowance. Their goal was to “produce a classless society by requiring an equal amount of work by members.” Sunday meetings began with a “Socialization Session” during which members talked about their feelings. They shared a belief that “people conditioned in Capitalist Society are sick” and their goal was to create “an equilibrium between production and consumption.” Needless to say, this group did not last long and few people remained by 1978, when it was purchased by Norbert and the Genesis group from Europe.

The former home to the Hailos Community is now a retreat called Bear Valley Highlands that offers unique vacation rentals. Here is its website.

There was at least one more intentional community in this area during the 1970s. Dedicated to the arts, Dandylion Landslide (it may have also been called Ambado) was formed by graduates from the Kootenay School of Art and an artist from Sweden named Wanda Twan. There were painters, weavers and potters living there together for a few years until it too broke apart, the common fate for most of the intentional communities of the 1970 and 1980s.