Located twenty-five kilometres east of Enderby along the Shuswap River is Kingfisher, home to one of the most spirited communities in our region. On the opposite side of the river from Mabel Lake Road, the homesteads are quite isolated because there are no bridges, and this is where two “back-to-the-land” groups set up in the 1970s.

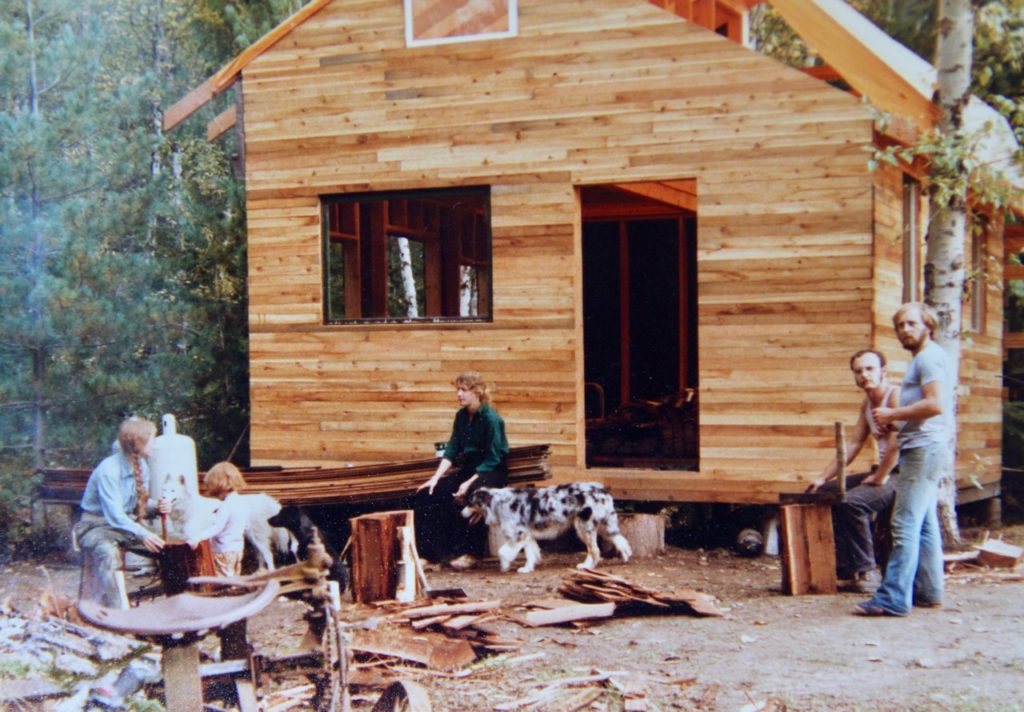

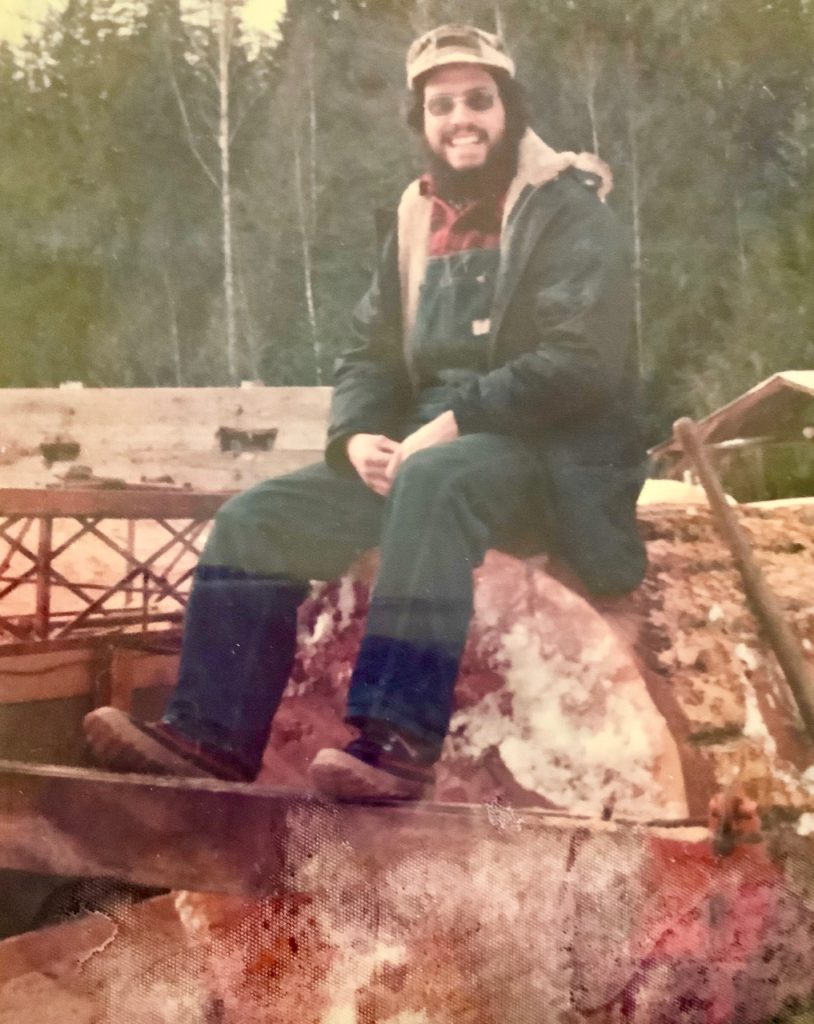

In 1974, Brian Lussin was finishing his education degree while also teaching in Vancouver when he decided to join his friends, the Bemisters and Liftons, who had formed the “Common Good Co-op,” which had a goal to set up an intentional community focused on building log homes. They found an abandoned homestead on the isolated side of the Shuswap River, which they applied to the then NDP government that was supportive of cooperatives, to lease the land. Rather than wait for the paperwork to be formalized, they began building their first log home on the property, which was extremely challenging given that all their supplies and equipment had to be ferried across the river.

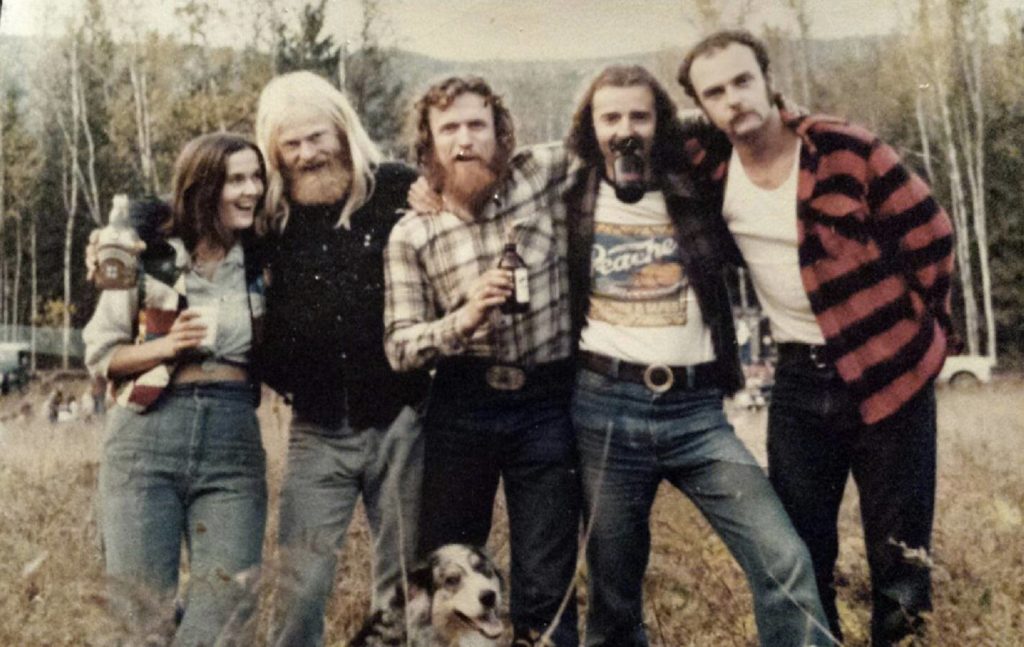

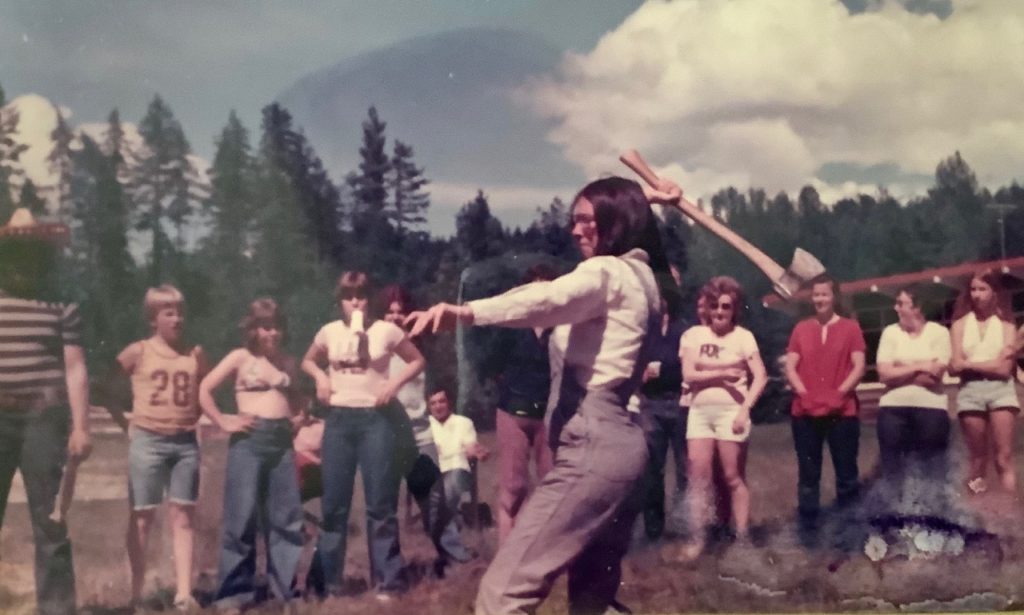

In part through the group’s connection to the Coalition of Intentional Cooperative Communities, more young people joined them that summer. A mobile dimensional sawmill was purchased initially to cut lumber for the log homes, but when the group needed income it was set up at a large sawmill site along the road to cut timbers and railway ties. Members also worked at construction jobs and since the Co-op was a legal entity, it was used to hire members for a few weeks and then lay them off so they could collect unemployment insurance.

When the NDP lost the election, their dream of eventually owning the homestead was dashed, along with the provincial government’s support for the co-op movement. Their completed log home had to be dismantled and was moved to the north side of the river and Brian purchased a new sawmill that he ran until 1989 when he returned to teaching. He and his wife Sue became stalwart members of the Kingfisher Community and continue to live there today.

Lorenzo’s Café was a long-time fixture in the local live music scene until it closed its doors in 2019. The café’s proprietor, Lorne Costley and his wife Marlene, first moved to the Shuswap in 1972 and initially stayed at the “Dirty Dirt Farm” near Falkland but they were frustrated with the politics involved in living with seven other people who each had a different idea about how to utilize the property. They then found their ideal property at Kingfisher, an old homestead with decaying buildings and an overgrown filbert orchard that had been planted in the 1940s.

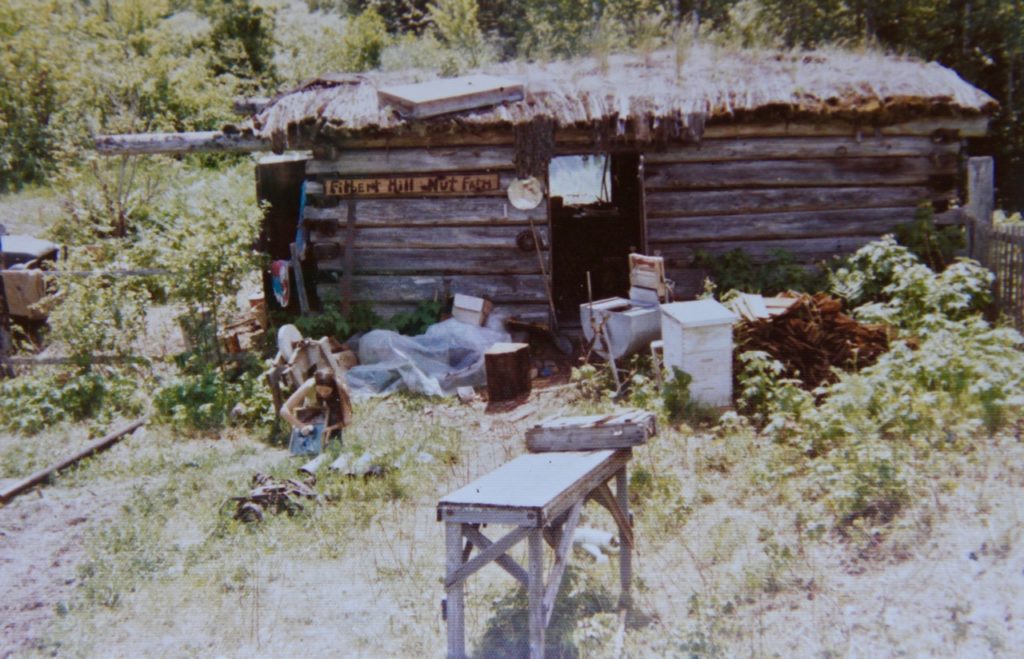

Their first summer was spent living in the old tool shed that had a cedar bark roof, which grass and moss growing on it. They named their property Filbert Hill and began building a cedar-shaked dome, but for their first winter they rented a cabin on the north side of the river. In the following years, their friends the Koops and Brent Schindell joined them as property owners and their farm became a community, with each family building their own homes and growing their own gardens.

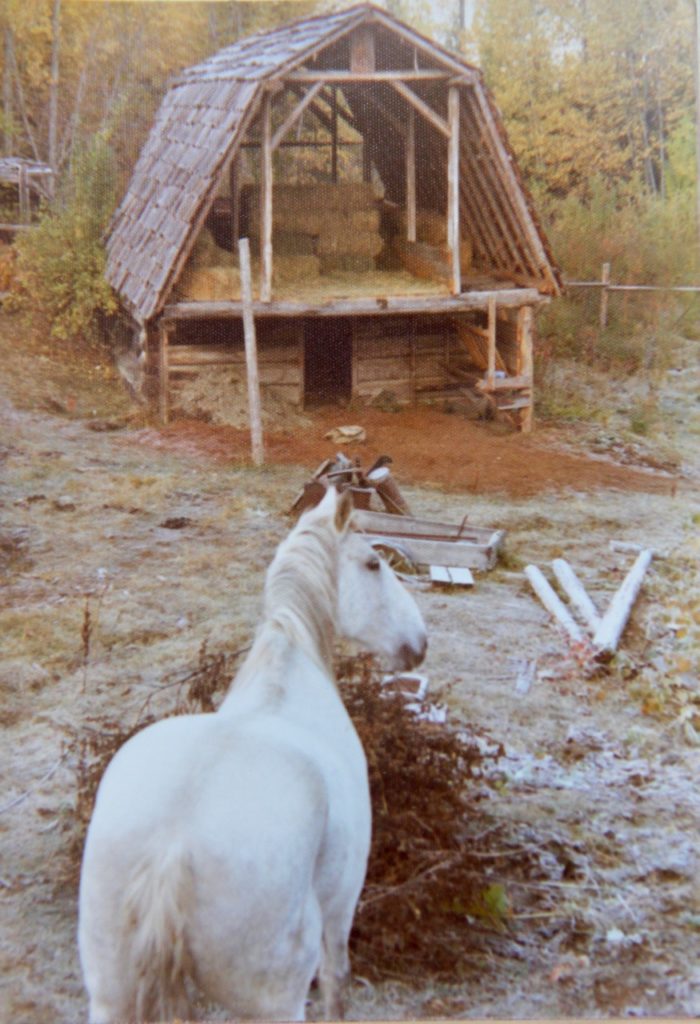

While the filbert nut harvest did provide some income, they depended on their tree-planting and logging jobs to pay the bills. Lorne remembers how they had “boundless energy, enthusiasm, optimism and ideas,” but what was key to their persistence in the face of so many challenges was their youthful “naiveté.” Despite the lack of electricity, phones and good access, they enjoyed their privacy and their many work parties, pot-luck dinners and music nights. They had an old work horse for hauling wood and supplies and used a 1952 army truck to cut their hay. Slowly, Lorne’s partners drifted away to pursue their careers. Brent became a successful musician and won a Juno with the Gerry Doucette band, while Greg Koop formed a construction company. Finally, in 1979 Lorne moved to Enderby to start his Filbert Hill furniture manufacturing business. The farm became a summer get-away spot, even though the buildings decayed, and the dome collapsed, due in part to the triangles that were fastened with filbert twigs instead of bolts. In 1998 the property was sold, putting the final end to another intentional, back-to-the-land community dream in the Shuswap.

POSTSCRIPT

Common Good Co-op originator Duane Bemister is now a computer consultant living near Salmon Arm. Here are his recollections of those early days, “….we planned and hiked the fifty mile long West Coast Trail on Vancouver Island. This camaraderie eventually led to us quitting our jobs, moving to Mable Lake and the birth of the Common Good Co-op. We found a small community called Kingfisher nestled beside the Shuswap River that felt like it must be Paradise. We experimented for two years, with an alternate life style that was at times challenging but also incredibly rewarding. I learned a lot about human nature, our capacity for sharing and caring, but also our primal desire for privacy, friendship and respect.” Duane remembers how they lived in tepees and tents the first year and they were training kids from the states who would sleep on the floors. In the winters they rented houses and blended in with the Kingfisher community. He also remember travelling to Lumby for music nights at the commune, which had “weird food.”

Lorne has found memories of their years at Filbert Hill, “it was an amazing time!” During the seven years they lived there, two children were born. Eventually, they became fairly self-sufficient and made good use of the root cellar for storing food over the winter. They raised cows for milk and meat as well as pigs. Often they supplemented their food supply with bear meat, because the filbert trees would attract them. There work horse was named “Moose,” but when it came time to haul in hay they realized there was more work maintaining the horse than the work done by the horse. There was no hydro, so they use generators, propane fridges and kerosene lights. Access was always a challenge, as either they had to canoe across the river or go the very long way on a rough road via Hidden Lake. In the early days, there were times the canoe dipped and they ended up getting wet. Eventually, they decided their needs were not being met living so remotely and the move into town would provide more income for enjoying a better lifestyle while their children were growing up, such as being able to go skiing at Silver Star and enjoying a movie in Vernon.