Thousands of young people in North America moved to the country in the late 1960s and the 1970s, with some setting up intentional, cooperative communities, including me. By the mid-1970s, there were dozens of these communities throughout British Columbia and an organization was formed called the Coalition of Intentional Cooperative Communities (CICC) to share knowledge and build up the movement. Conferences were held quarterly, and a newsletter was distributed after each one.

A contact list in the April 1977 CICC newsletter lists approximately 230 individuals, communities, organizations and businesses throughout the province. There were 14 listed in the Shuswap region, including one in the Salmon River valley, one in Falkland, a few in Grindrod and Enderby and the majority located in the Lumby/Cherryville area. While in the process of doing the research for this column, it was a delight to discover that I know some of the people that were part of these local cooperative communities.

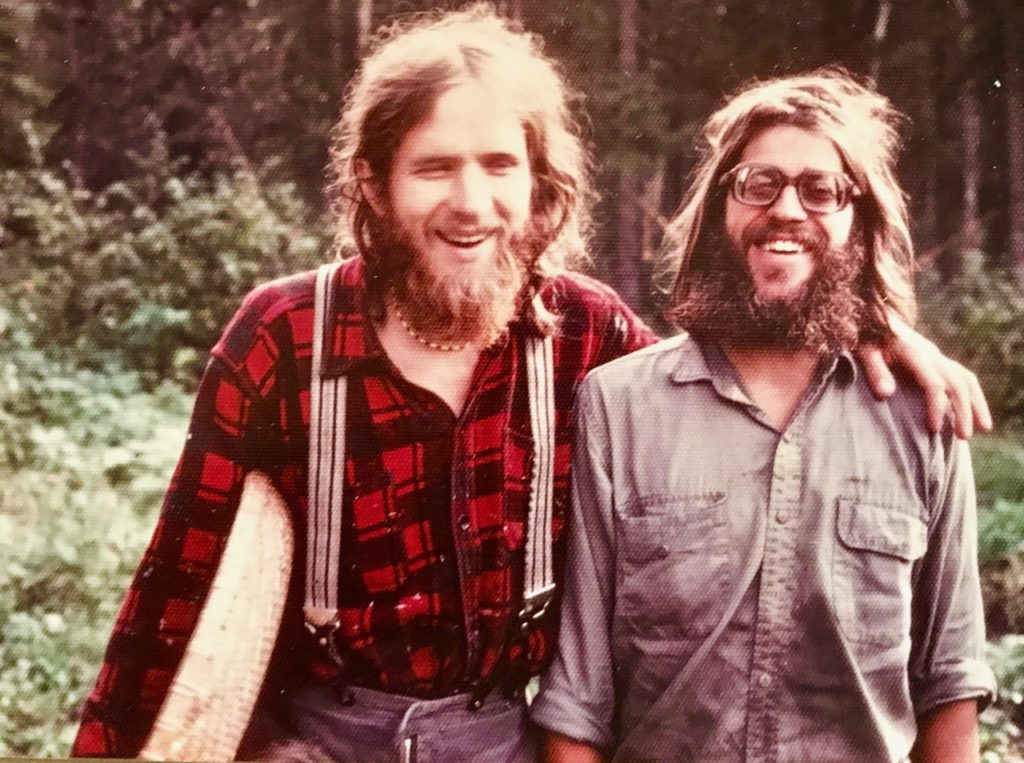

One of the best examples of a local intentional community was the Alternate Community near Lumby on Bessette Creek that began when Robin and Ken LeDrew moved to 14 acres and brought some of their artist friends with them from the Vancouver art collective they had been part of in the late 1960s. Robin explains how their community, which was to be based on experimental architecture, went through a number of phases that began with an early dis-organized, anarchistic-like scene with full-moon parties and people living roughly with many hardships.

After spending a year away that included time at a well-organized commune in Florida, they returned with intentions to revamp their community by focusing on more productive and progressive ideals, yet they found their land in disarray, with collapsed domes and the taxes unpaid. The next phase began when Ken returned from Vancouver after taking a course in intentional communities and with him were 30 people eager to begin communal living at the property.

The group became a well-organized cooperative, with 2-3 meetings per week, at which decisions were made by consensus. All income was pooled, and they shared three vehicles. A huge garden fed everyone, and businesses were started, including a health food store in Vernon, a publishing company and a tree-planting and cone-picking company. With success came the inevitable problem of land ownership and when the plan to put the land into a trust with everyone owning shares fell through, people left to become established elsewhere on property they owned or rented.

Some people stayed and others came to experience the next phase based on New Age philosophies that included Gestalt Therapy, dream circles and other alternative lifestyles. Today the property is just another family farm, with only a few of the originals left. In addition to her work as an artist, Robin had a successful career in social work and continues to contribute to the wider Lumby community as the president of the local arts council.

Robin remembers hosting one of the CICC conferences at their farm in 1977 and handling the logistics of feeding and housing 50 or more people from around the province for a weekend. She reminisced, “we talked endlessly about progressive ideals and how to change the world, but in the end, the world changed us and change happened anyway.” She also notes the irony of how they had to cope with living in what was then a conservative community, while now cannabis is legal and living close to the land has become more mainstream. However, Robin wishes that more young people could have similar opportunities today, as living off the land with others builds character and teaches the values of cooperation.

There are many stories from those idealistic times, with more to come in subsequent columns. Perhaps what is most interesting is how history repeats itself. Many of the early settlers that left the cities in Europe to homestead here over 100 years ago for some of the same reasons that inspired us to move onto the land in the late sixties and seventies. Now today, there are young people who are once again moving to the land to grow food and share the work and the joy of country living.

POSTSCRIPT

The self-described “amorphous network” Coalition of Intentional Cooperative Communities only lasted a few years, as did many of the communities. Their newsletters, called Open Circle, reveal just how energetic and idealistic these young back-to-the-landers were, as many were hoping to change the world for the better by living communally. These young people were inspired in part by the many books, magazines and music from that time period, including the Mother Earth News, the Whole Earth Catalogue, the Co-Evolution Journal and The Smallholder from Argenta, B.C., as well as popular music like Canned Heat’s “Going up the country.”

There were no holds barred in the Open Circle newsletter pages, as the disagreements were presented alongside the dreams and aspirations. One group in the Cariboo, which still exists today (now named CEEDS for Community Enhancement and Economic Development Society), called Ochiltree were practical, hard-working farmers who branched out to help others in the wider community, including the local First Nation. They were at odds with the dreamers and their spiritual, healing circles, and threatened to pull out of the Coalition and start their own newsletter, which they eventually did.

In a 1978 newsletter, Ochiltree wrote about the recent Silverhill Gathering, “Healing circles are just p;art of a phony, metaphysical bullshit philosophy that promotes passiveness and self-love. Needless to say, the healing circle did not produce any concrete ideas. Building a true alternative to straight society involves a lot of self-struggle. We have to rid ourselves of all the bourgeois philosophy that places the interests of people ahead of Mother Nature’s. E.g., food faddism, vegetarianism, mysticism and spiritualism.”

Despite these views, it was the new age activities that helped the Alternate Community thrive in its third phase. In addition, the financial obligations were made less onerous, as community members simply shared the expenses rather than pool all incomes. Successful food business owner and former community member, Richard Vignola fondly remembers their work with gestalt therapy and believes that their experiences were very special as they pushed hard for transformation. He recalls how the previous group had been quite intellectual, while they were more spiritual and that he and his wife Sue will always cherish their times at the farm near Lumby. Richard still thinks that communal living is the “way forward” and is impressed with the number of “young people making a go of it on five acres or more.” From Quebec, Richard decided to move to B.C. and live in the country after attending Woodstock where his life goals changed after the experience.

Successful apiarists Reg Kienast and Dianne Wells also appreciated their time at the Alternate Community. Reg remembers how it was a practical time filled with good intentions and that by sharing the work and resources it gave them more time to get involved in the arts and become more creative. After they left the community, most of them made significant accomplishments.

Throughout the Open Circle newsletters there are reports from Tyhson who was part of the Texas Lake Community, who turned out to be the same Tyhson Banighen that participated in our successful efforts to save wilderness here in the Shuswap in the 1990s. In the 1970s, Tyhson helped run a youth hostel at Texas Lake near Hope, B.C., where they had a large organic garden and many travellers would stay there. The operation was part of the faith-based Harmony Foundation and when they began to set up a network of cooperative communities across the province, there was some blow-back from Coalition members, especially Ochiltree who “was suspicious of humanity-oriented organizations, believing that too much emphasis on humankind is a ripoff to Mother Earth.” Eventually, a “temporary marriage” was made between the two groups and Tyhson remembers creating and mailing out some of the newsletters using their Gestetner machine. After their experience at Texas Lake, Tyhson’s group purchased 320 acres in the Kettle Valley, where they changed the name of their organization to the Turtle Island Earth Stewards. Eventually, Tyhson moved to Salmon Arm and for a number of years was the coordinator for the Salmon River Round Table and organized much of the restoration work on the river.

Will communal living ever become popular again? There are certainly advantages to like-minded people sharing both the work and the fun of group living and it does mesh with the need for society to become more sustainable. As well, so many generations have now passed since the nuclear families replaced the extended families, with one of the outcomes being more social and psychological problems that require a vast increase in government run social services. There would certainly be advantages in today’s world where the cost of owning a home or piece of property is far beyond the means of most people. However, the New Age model might be beyond most people’s comfort zone, such as one of the Alternate community’s practices, the Dream Circle, when they stayed up sharing stories around the fire then slept there waking up together in the morning sharing their dreams. Those were definitely unique, esoteric times that deserve reflection now and there are more intentional community stories to come.