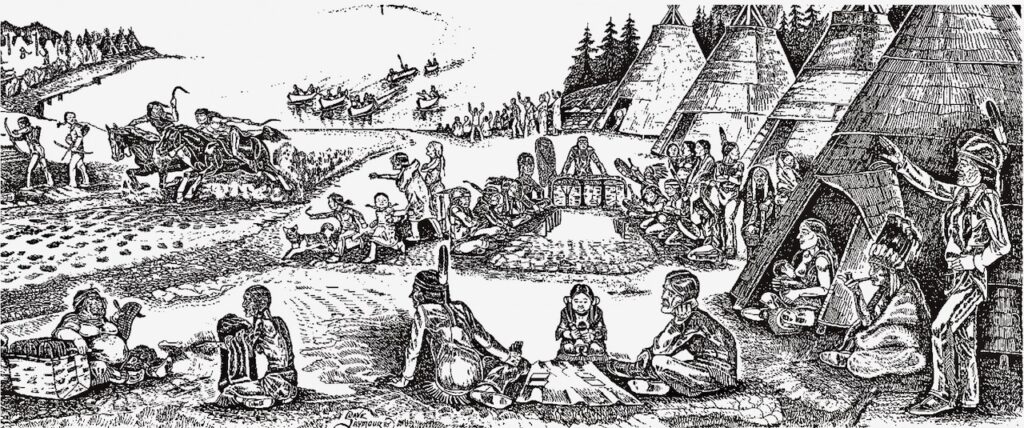

Nearly one-quarter of famed ethnographer James Teit’s book, “The Shuswap,” is devoted to their way of life, which was in many ways more structured and disciplined that those of the Europeans who displaced them. No doubt it was easy for the fur traders, gold miners and early settlers to malign and take advantage of the First Nations, because they did not understand or respect their culture and they coveted their land and resources.

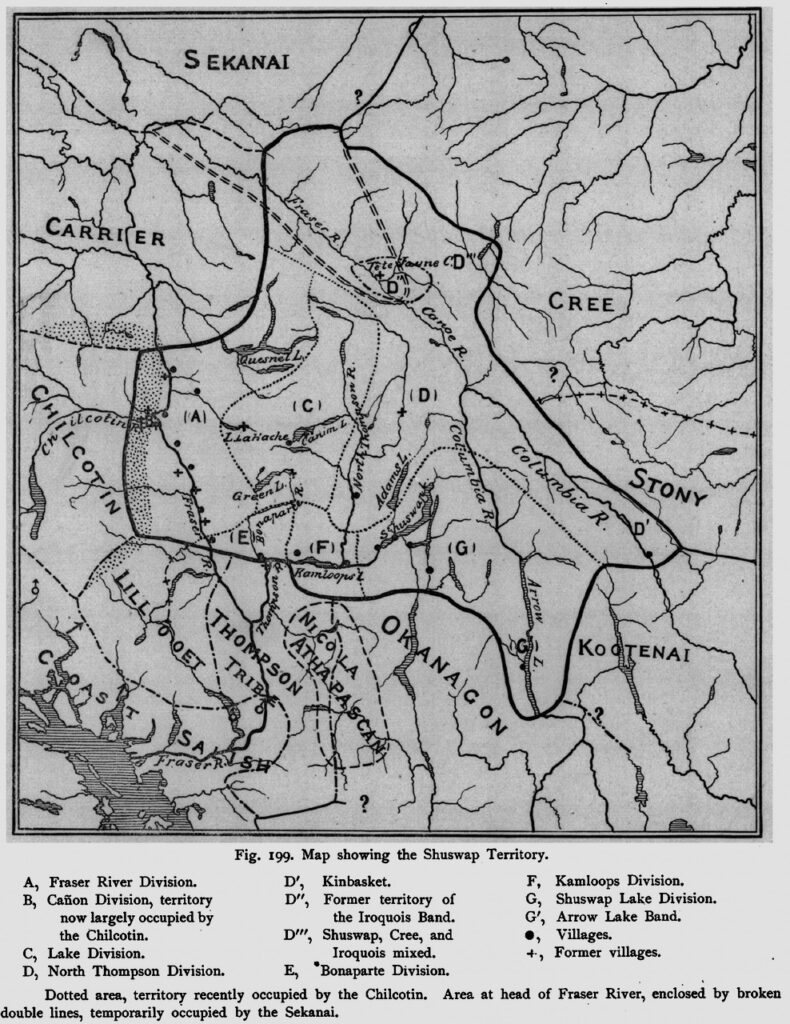

Up until European diseases began killing BC’s Indigenous peoples in the late 1700s, the Secwépemc people had successfully maintained their language and culture for many thousands of years as neighbours to other cultures who had different languages and customs. For each of their communities to thrive, they relied on their strong and capable leaders to make the right decisions that benefited everyone. They had many chiefs, all elected as the best qualified for their roles, including taking charge of warfare, hunting, and even dancing. There were also hereditary chiefs and when one died, his position was either filled by their oldest son or was elected by all the closest male relatives.

Social structure varied in different regions. In the eastern communities, chiefs were not considered royalty, nor did they have special privileges, whereas in the west, there were three classes: noblemen, common people and slaves. Crests were used to signify hereditary groupings. In both regions, chiefs acted upon the best interests of their people and made sure that food supplies were shared equally.

There was no private property and although each community had their recognized hunting, trapping, gathering and fishing locales, and other communities were allowed to use these areas. In the western communities, potlaches were sometimes given by one crest group to another. Those receiving gifts were expected to return the favour with gifts of equal or slightly better value later.

One true measure of how Secwépemc society was well structured is the strict way that their children were raised. Girls carried small baskets to gather materials for making miniatures, such as bags, mats and baskets, so to become adept at using their fingers for stringing roots and sewing. They would also set fire to small heaps of dry needles on their wrists and arms so they would be better able to withstand pain of all kinds, especially childbirth. Girls were closely watched until marriage and thus there was little “immorality” amongst young people.

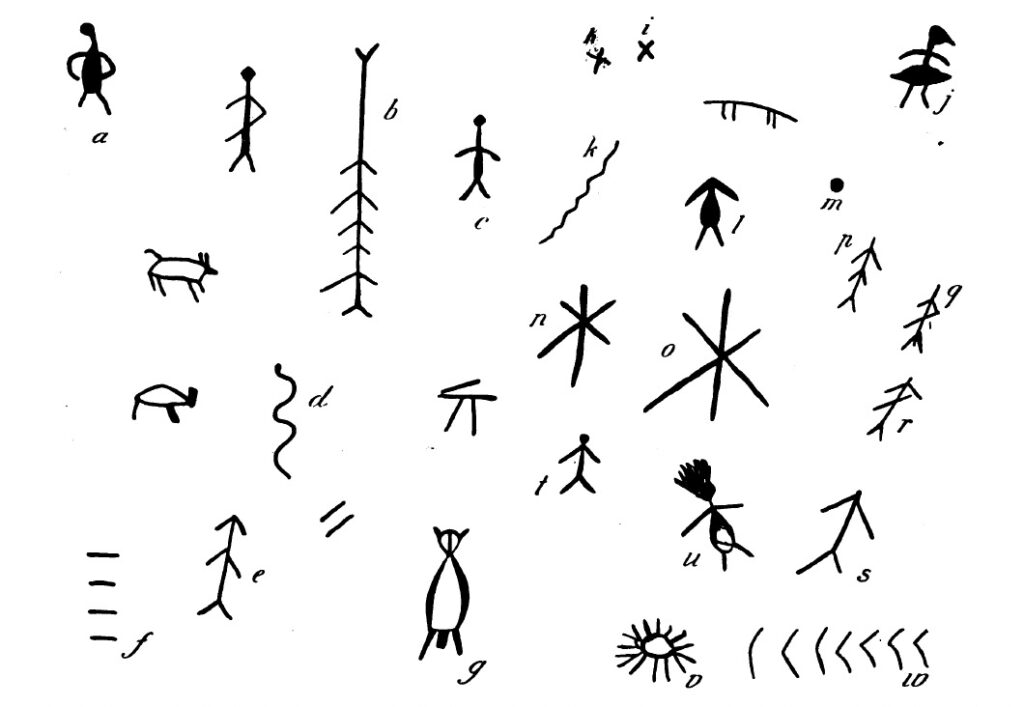

Boys began their training around the time of puberty and would live in seclusion for anywhere from a few days to a few weeks. During this time, they fasted and trained themselves with the goal of obtaining their “manitou,” meaning their spiritual power. They trained for the profession they have chosen, such as shaman, warrior, hunter or gambler by running, jumping, and doing many types of gymnastics. They also cut their bodies to gain the ability to endure pain. Both boys and girls painted pictures on rocks of objects from their dreams, which was done to hasten their attainment of their manitou.

The Secwépemc had an intricate spiritual belief system that included a conception of the origin of the world based on mythological creatures who were part animal and part human. Key to their beliefs was the emergence of Coyote who was gifted with magical powers and did most of the work needed to benefit people, such as introducing salmon into the rivers. They prayed, believed in guardian spirits and observed ceremonies to impact the weather and other natural events. Most men had shamanistic powers and at least once during the winter the people gathered in their underground houses to sing songs that spoke to what was important to their spirits.

Many of the teachings took place in the evenings after games were played. Elders told stories about wars and hunting, and mythological tales, including comic ones. They would also address the young people urging them to follow the “rules of proper ethical conduct.” Such a far cry from today’s video games, social networking and overindulgent, fast paced, consumer society.

POSTSCRIPT

The Secwépemc way of life evolved over thousands of years leading to a system that allowed communities to thrive in ways that promoted sharing, cooperation and equality. While there were wars and slaves, there was also peace and trade amongst the many nations who managed to live in relative harmony with each other and with the natural world. This lifestyle was impacted decades prior to first contact, due to the introduction of diseases that were brought north from the U.S. via Indigenous trade.

Europeans dismissed First Nation’s spiritual beliefs as unbelievable superstitions and yet Christianity and other western religions also include miracles and holy spirits. Here is an excerpt from Teit’s The Shuswap that describe the Secwépemc spirit world:

Spirits – the land and water mysteries – inhabit many places, most of

which are harmful. The land mysteries live chiefly in mountain-peaks and

caves; and the water mysteries, in certain lakes, especially those having no

outlets, and in waterfalls, bogs, and springs in the forest, particularly those

surrounded by moss and reeds. Certain marshes and muskegs also have

spirits. Ancient rock-paintings have mysterious powers, and may hide and

show themselves at will. They are supposed to have been made by people

long ago; but through the agency of the dead, or by the supernatural

influence remaining in them, they are in a manner spiritualized. Some people

think they were made by the spirits of the place or by beings of the

mythological age.