Part seven and the final column in the series about a best-case scenario future

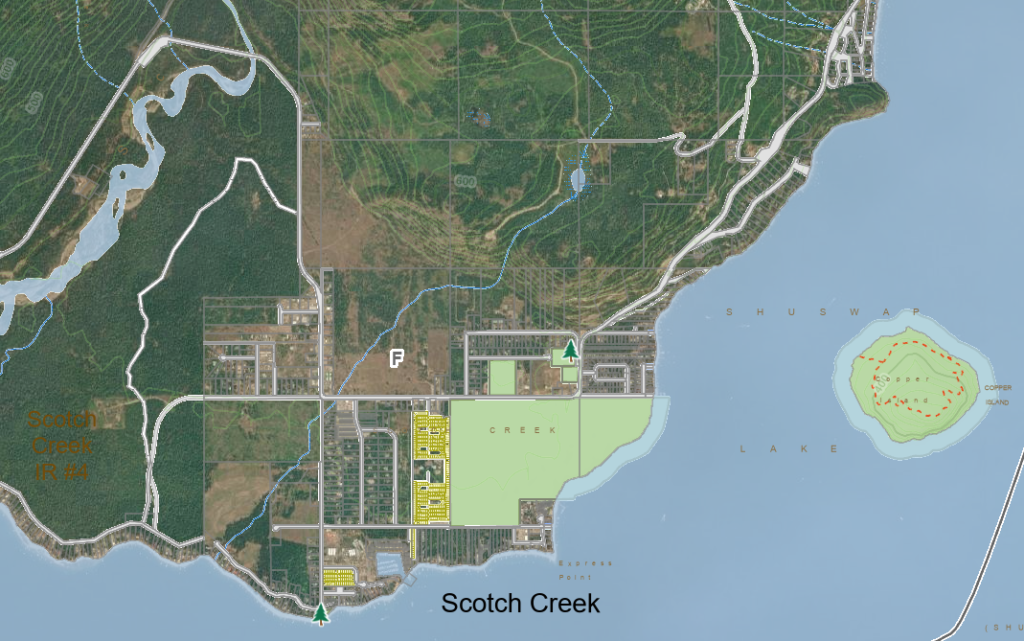

By the year 2052, the North Shuswap community of Kwikoit*, formerly known as Scotch Creek, is a thriving small city that includes many small, intensive farms. When the agricultural land reserve system was revised to allow for large acreages to be subdivided into one-hectare parcels to accommodate craft farms, the community began to grow sustainably.

Within the former large vacant acreages of prime agricultural land, are dozens of homes filled with young families, greenhouses, processing and storage facilities and small houses for staff. So much food is produced, that much of it is shipped to larger centres. Food production continues year round, with vegetables grown indoors in vertical farms during the winter months. Aquaculture is popular, with the wastewater used to fertilize crops.

Throughout the community there are condos, apartment buildings, co-op housing, a community hall, schools, municipal buildings and commercial hubs and most are accessed using small electric vehicles, bicycles and buses. Many homes are built partially underground in the surrounding hills to keep cooler in the summer months.

The tourism economy that at one time only flourished during the summer months is now primarily based on biking, other adventure sports and local history. The world-class biking trails that descend from the bluffs attract riders from throughout the province and Canada. Youth biker culture permeates the community that comes alive nightly with music, dance and celebration.

Reconciliation with the Secwepemc people that began in earnest when the community changed its name has resulted in cooperative land use management. The local Skw’lax people now have control over much of the land base in the Kwikoit Creek watershed and land use in their reserve lands is compatible with the rest of the community as it now includes long term leases for small farms as well as houses, trails and parks.

Forest management is primarily focused on wildfire protection, with deciduous trees replacing conifers and water reservoirs in the hills. Logging is restricted to thinning and removal of dead and dying trees, as the overall goals for forestry are carbon sequestration, ecological restoration and biodiversity protection.

History buffs visit the community to hike Kwikoit Creek gold trail once used by the Chinese railway workers in the 1880s, where they pan for gold and explore the replica log cabins, as well as the replica Secwepemc village. The yearly gold rush festival includes the adventure race along the trail and evening festivities.

Another major attraction is the new provincial park at nearby Lee Creek that includes the canyon, nearby bluffs and much of the watershed. Attractions include the popular Lee Creek Bluffs mountain bike loops, zip lines, the canyon trail that has numerous bridges, and the waterfalls. Another feature is the old growth forest found in the steep canyon, where the trees are protected from forest fires.

What is most remarkable is how close knit the Kwikoit community is, with dozens of active clubs and organizations. Everywhere there are examples of how cooperation and collaboration help ensure that the community is able to thrive despite the challenges from extreme weather events and rising temperatures. Community spirit extends to aesthetics, as the small city prides itself on its image with beautiful landscaping and picturesque architecture.

The overall theme for Kwikoit and many other similar British Colombia communities is resilience, as in order to not only survive but also to flourish, local citizens and governments are focused on finding the best ways to adapt to the rapidly warming climate.

*On a map, the northern tributary of Scotch Creek is named Kwikoit Creek.