The goals of truth and reconciliation include acknowledging past injustices, as well as working towards healing and restoring good relationships through recognition, education and action. They should also include rejecting the all-too-common narrative that Indigenous peoples were primitive societies. While Europeans arrived in North America on sailing ships with deadly metal weapons and came from countries with advanced architecture, universities, books, and art, Indigenous people had superb mental and physical abilities, complex skills, intricate technologies and well-developed, social structures based on sharing rather than on greed and power.

A good way to better understand the lives of the Secwépemc people who have lived here for over 10,000 years is to read The Shuswap, the 1909 memoir by ethnographer James Teit, who also wrote ethnographies of several other First Nations. Although there had been over 100 years since first contact by explorers and fur traders during which time many lifestyle changes had occurred along with high death rates from smallpox and other diseases, Teit was able to glean great insights from the elders he interviewed who had first-hand knowledge of the old ways.

Although one might consider stone tools and arrow-points, and wood and bone utensils as crude when compared to those made of metal, the degree of skill required to make them was extraordinary. First the stones, including obsidian, jasper, agate and quartz had to be found in the mountains and in some places quarried and then precisely chipped, often with jade, to create sharp points and edges for points, knives, chisels, and axes or rounded and flattened for mauls, mortars, anvils and hammers. Tools were also carved from wood, bones and antlers.

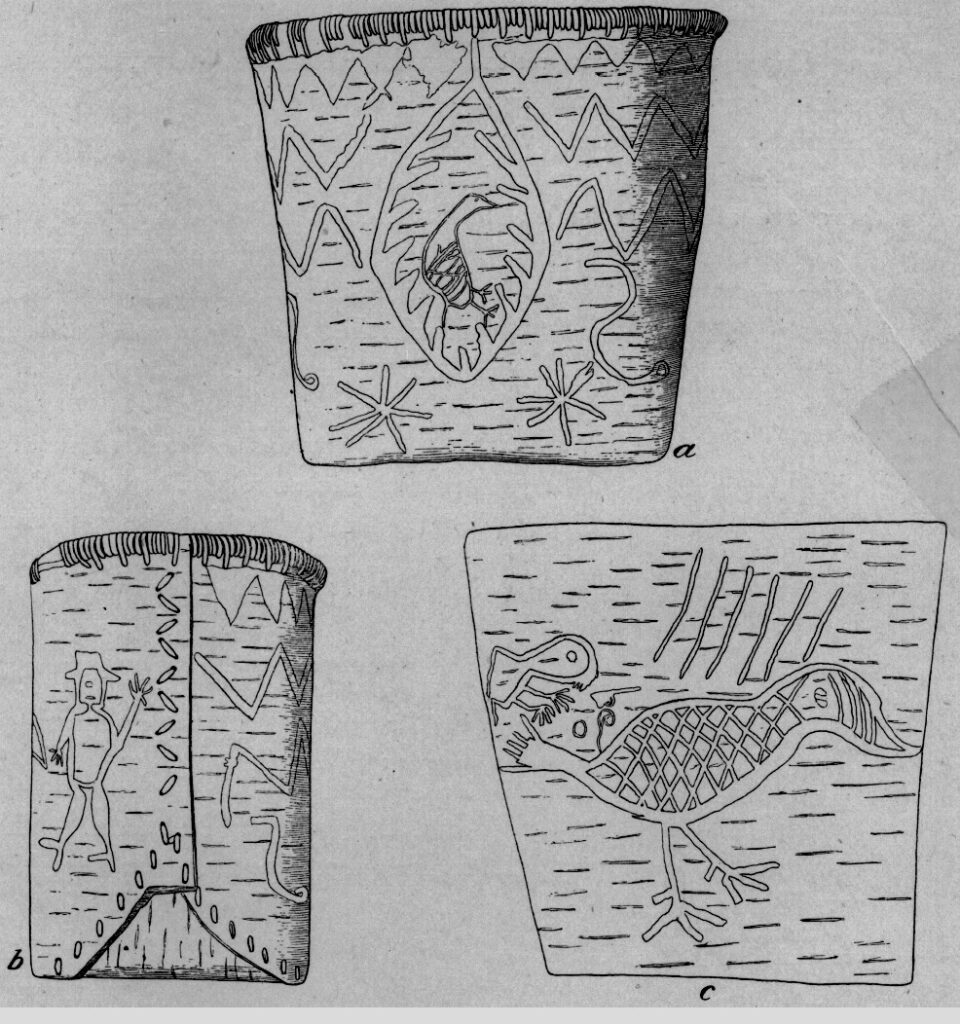

Basket making was another highly skilled occupation, as these containers were used widely for storing and cooking food. Birch bark was commonly used for baskets by sewing pieces together with split spruce roots and then decorated with etched pictographic or geometric designs and with rims that included swan quills, cherry bark or horsehair. Intricate coiled baskets were also made using cedar roots or spruce roots. Mats were also woven out of rush, tule, bark or grasses and used to cover summer lodges, for ground coverings and for drying fruits and roots.

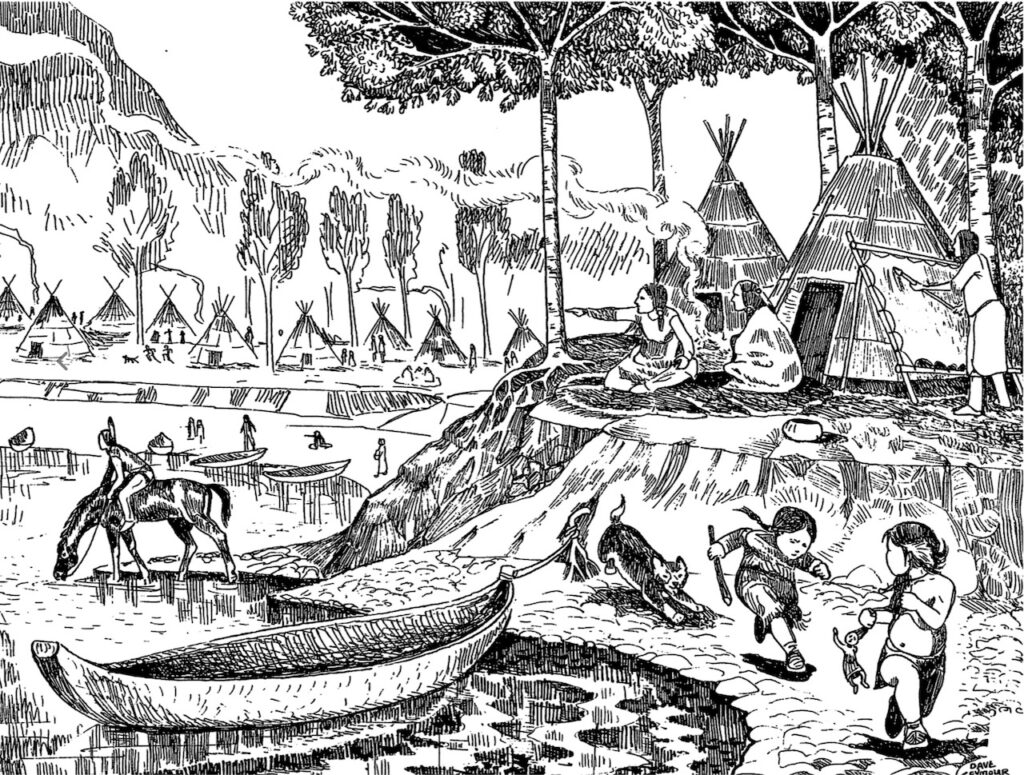

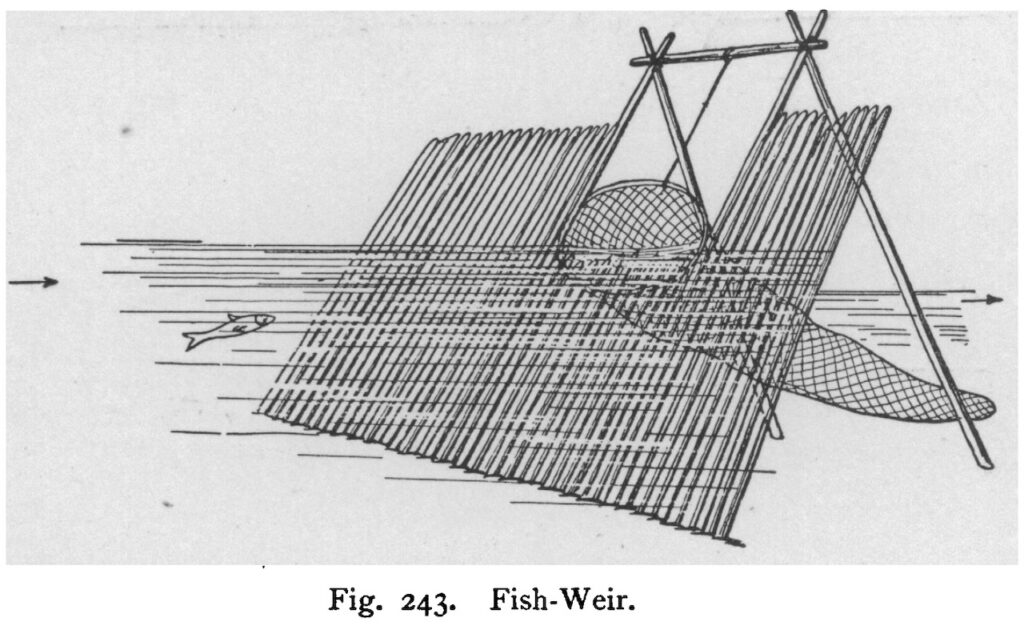

Living here in tune with the natural world, the Secwépemc developed complex methods and tools for fishing. They made and utilized nets, spears, sinkers, hooks and lines to catch both freshwater fish and salmon. Fish weirs were built out of tree branches to corral the fish so they could be speared, netted or caught in traps. Indian hemp (dogbane) was stripped to make the twine for the nets and fish lines and to build the fishing structures.

While fish, meat and berries were key components of their diet, the Secwépemc also utilized many types of plants and roots for both food and medicine. Preservation methods included boiling berries, pressing them into cakes that were dried, threading the roots on strings to dry them, wrapping salmon roe in bark and burying it and storing salmon oil in bottles made from fish skins. Arrowleaf balsamroot was a staple, and the young shoots were steamed, while the roots were baked in pit ovens to make them edible.

It was not all just hard work every day to survive, as there was ample time for celebrations and other social events that included singing, dancing, storytelling, sports, games and gambling. Most Indigenous people held festivals during the summer and winter solstices, at which songs were sung that were thought to come from the spirit-land. The Secwépemc, like other nations, were intensely religious and their ceremonies were “expected to hasten the return to earth of the souls of the departed, and the beginning of a golden age.”

With no books or written language, all knowledge was passed down from elders to the youth, and everything was memorized, unlike today when we depend on computers, smart phones and artificial intelligence to provide the all the information we need. While we exercise and go to gyms to keep in shape, Aboriginal people were by nature, strong, swift and agile. By far, the major difference was that First Nations were in tune with nature, while modern society has been destroying nature for centuries.

POSTSCRIPT

Although Teit’s book, The Thompson Indians of British Columbia, was re-published in 1997, his book on the Shuswap remains out of print. Fortunately, there is a project underway to republish his Shuswap book next year, which will include a new introduction and a brief biography of Teit. Currently, this treasured book can be downloaded for free as a PDF from the American Museum of Natural History website.

Group portrait of Chiefs at New Westminister. Standing L-R: Ta o’task (Canoe Creek Band); William (Williams Lake); Sitting L-R: Ma nah (Dog Creek); Quib quarise (Alkali Lake): Se-askut (Shuswap); Timpt Kahn (Babine Lake); Silkosalish (Lillooet); Kam-eo-saltze (Soda Creek); Sosastumpt (Bridge Lake) – Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park caption