A new BC Wildfire Service report has surfaced about the Shuswap firestorm that includes details about how the situation quickly became out of control soon after the backburn was ignited by a helicopter drip torch. This online report, called a Facilitated Learning Analysis, was prepared as part of the follow-up to the joint WorkSafe BC and the BC Government Employee’s Union investigation into the near-fatal entrapment of the Brazilian crew. It includes photos, videos, interviews and timelines to describe what happened and how staff reacted to the crisis.

Several factors resulted in what can now be verified as a disastrous decision to do an aerial ignition as a last ditch, “hail Mary” effort to prevent the Adams East wildfire from advancing into North Shuswap communities. Two days prior to the ignition, the leadership changed as a BC team replaced the exiting Australians. After the fire blew up that night, there were mounting concerns that the anticipated advancing cold front would blow the fire into the community in two days, which was confirmed by computer modelling.

Consequently, a hasty decision was made to do the backburn using the Hydro right-of-way as the control line, even though as the report explains, “views were mixed,” as one staffer “expressed concerns about the proximity of the cold front.” The decision was finalized on the morning of the 17th despite the weather prediction that showed how winds were predicted to shift at 9:30 pm. Evacuation planning was also discussed, including the complications due to the one way in and out road and the predicted congestion.

Even though the window to do the burn began at 2 pm, the aerial ignition did not begin until 4:15 pm and it was completed by 4:55 pm. The goal was to “widen a fuel free area to prevent aggressive fire growth.” They soon realized that there was a need to burn off the fuel between the powerline and the backburn, because the helicopter could not get close to the powerlines. Thus crews, who had never done hand torch burning before, had to be sent in without adequate training, without clear instructions, without adequate tools and with an inadequate amount of liquid fuel that had been poorly mixed.

The road was rough, which slowed the operation and soon the Brazilian crew was putting out spot fires. In the air, the helicopter coordinators observed the scene with “disbelief” as there were significant risks given that night was closing in. Winds began to shift at 7:30 pm and at 8:08 pm the backburn blew across the powerline forcing crews to make a hasty escape. Some trucks drove down the side road into Lee Creek and one nearly flipped over as it had to avoid a burning slash pile.

Due in part to the language barrier, the Brazilian crew went in the wrong direction and became trapped. They survived because they were parked on the right-of-way where there was little fuel, and the flames were minimal. Just prior to sunset, the helicopter coordinator observed the backburn spreading into both the Scotch Creek valley and into Meadow Creek. Later that night, a crew observed that the fire had spread across the Scotch Creek forest service road at the 5-kilometre mark, while another crew was in Meadow Creek observing the spread of the fire.

A debrief about the entrapment was the focus on the following morning and the team began to prepare for the cold front and the anticipated significant growth of both fires. It was not until 11:30 am that preparations began for evacuation, but the order did not come until 2:15 pm for Scotch Creek and 4 pm for Celista, well after the fire was in those communities. As the winds intensified on the afternoon of the 18th, bedlam ensued because the Wildfire Service had to evacuate their camp, and residents were forced to defend their properties as the firestorm engulfed their communities.

Most of this report is focused on helping staff cope with the aftermath of the disaster and it avoids finding fault or making recommendations. The report’s goal is to simply foster discussion and learning as if it was a therapy exercise for stressed out wildfire managers. While it is the Forest Practices Board that is considering whether the decision to light the backburn was “reasonable,” this report points to another major, unaddressed concern. How could the Wildfire Service claim that their burn was a success at the same time as they were having to deal with the escape of the burn that endangered their crews and was observed heading to our communities, given that their overall goal is public safety?

POSTSCRIPT

CLICK TO READ THE FULL REPORT HERE – FLR – NOTE: The report was taken off the site a few days after this blog was published. Clearly, BCWS is more interested in hiding this information than allowing the public to know the truth about what happened during the summer of 2023 when their mistakes resulted in the massive destruction.

Here is the report (copied and pasted into a document, minus some photos, quotes and videos) –

Some quotes from the Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLR) report:

- Having a front-row seat to something you suspect will go horribly wrong is profoundly impactful.

- All 3 HLCOs experienced a sense of powerlessness as they watched from the air, trying to avert a potential tragedy.

With the FLR report are many other examples of the problems connected to these fires. For example, “During this period, the BCWS was facing significant challenges in their ability to coordinate the many varied resources being assigned to these complex events, with the situation rapidly changing and critical decisions being made under great time pressure. This system was being pushed to its fullest extent, resulting in a need to work with what was available, leveraging local support where possible, limiting risk and exposure to unsafe situations and sharing critical resources with other incidents to ensure protection of the priority 1 values.”

Also: “Later additions to the complex from successive lightning events included the Rossmoore Lake wildfire (K22024) which proved to be another challenging, emergent fire. This fire was 70 km west of the main group of fires that the IMT was tasked with managing and displayed consistent daily fire growth that challenged ground resources. The Rossmoore Lake wildfire had all the complexities to warrant a single IMT, however with the lack of resources and need for doing more with less, the assigned IMT had to constantly juggle which battles became the priority.

The fires within the Adams Lake Complex demonstrated persistent growth that challenged fire fighting efforts. One key difficulty was the heavy fuel loads in surrounding forests being receptive to spot fires that would gain momentum during daily periods of increased fire behaviour. Heavy equipment lines would be established where possible with plans for direct attack and ignitions to bring fire to these lines for containment, however it only took one quickly growing spot fire outside the guards to ruin multiple days of work. This was a daily challenge that occurred often amongst the three large fires, repeatedly disrupting plans and shifting priorities quickly.”

Most concerning was that resources were diverted to other fires:

“Compounding the situation, new fires had started elsewhere in the province, including the McDougall Creek Fire near West Kelowna, while other fires, like the Kookipi Creek Fire, were rapidly expanding, quadrupling in size. These fires threatened communities, driven by the same forecasted cold front. This initiated a number of resources such as structure protection and aviation being diverted from the Adams Lake Complex to respond to these emerging priorities.”

August 18, 2025 UPDATE

Another BSWS report regarding the fire crew entrapment was obtained in July. There is not much new information in it other than this report by the staff in the helicopter keeping an eye on the hand burning operation:

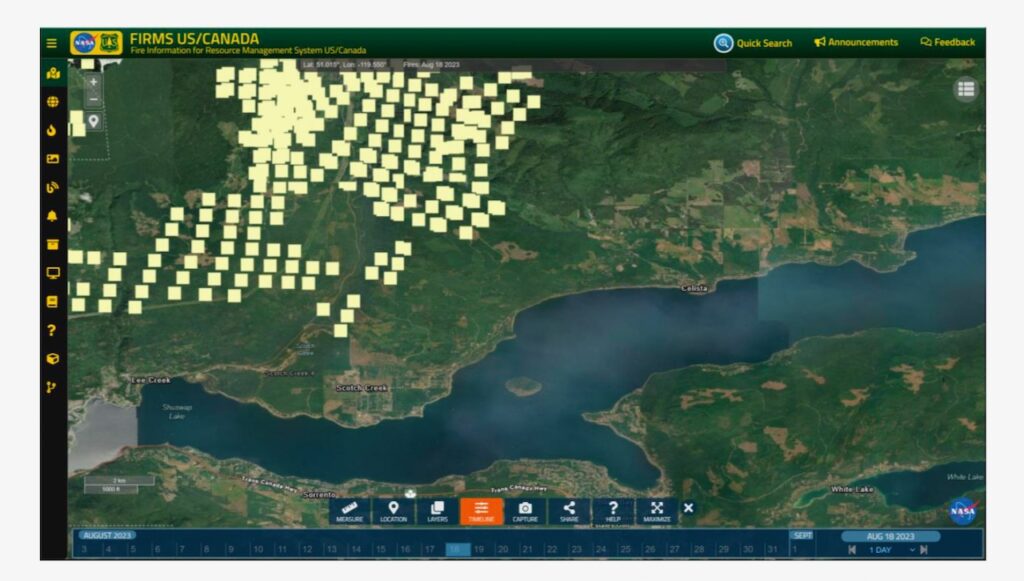

Also, a re-read of the Fire & Flood report about the massive water cannons used to protect Scotch Creek reveals this map that the crew had early on the morning of the 18th.