After the Bush Creek East wildfire devastated over 80 percent of Tsútswecw Provincial Park, its future is looking most uncertain. Prior to the fire, the trails above the bridge to the gorge and all the way to Nikwikwaia Creek (Gold Creek) were used by many hikers, mountain bikers, kayakers and trail runners every day and the parking lot was often nearly full. Now it and most of the trails are closed as the forests are burnt to a crisp.

The Flume Trails along Loakin (Bear) Creek, that featured the remnants of the log flume built by the Adams River Lumber Company over 100 years ago were the newest addition to the park and had been recently improved with new bridges, stairs and guard rails. It too has been destroyed and it is uncertain if the steel bridges can be restored or when this part of the park will be open again.

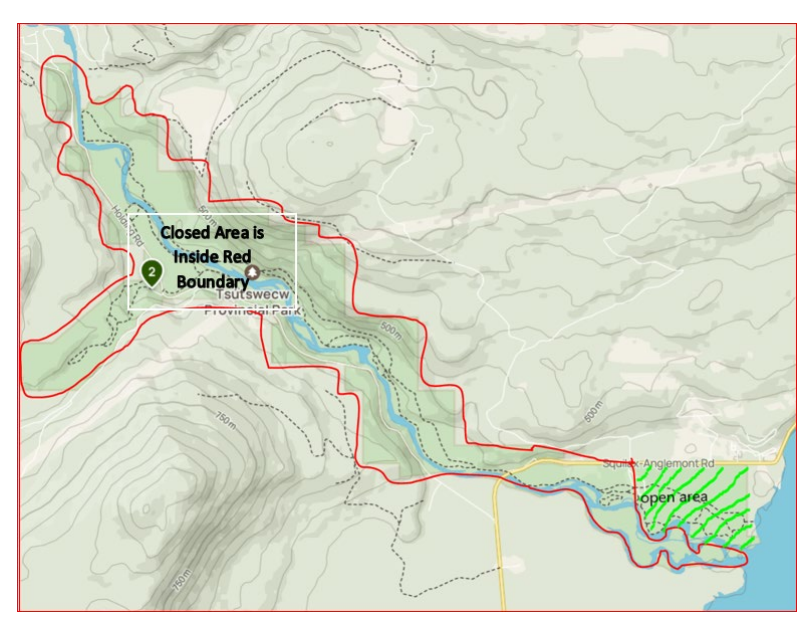

Much of the park is closed due to the danger that the burnt trees pose to the public, because they could fall on visitors, especially in a windstorm. The process to reopen the trails first involves a post-fire damage assessment and then the danger trees must be taken down. Fortunately, the park received funding under the federal Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements (DFAA) and that assessment is now complete. Already, danger trees along the trail from the parking lot to the bridge have been felled and this trail is now open.

It has been determined that it would cost up to one million dollars to restore the trails, bridges and structures including the bridge to the island loop trail and above the highway bridge, and the funds have been allocated for this work, which is slated to begin in 2025. Although it will be great to have these trails open again, visitors will still be hiking or biking through a burnt landscape for many years. Unless some effort is made to reseed new trees from the air, it could take many decades before a new forest emerges, as there are few alive to produce seed cones for regeneration.

Prior to the wildfire, invasive weeds were a concern in the park and these concerns increase due to the flush of nutrients after a wildfire. On September 26th, the Columbia Shuswap Invasive Species Society (CSISS) held a workshop for land managers, community groups and members of the public in the park that included a tour. The event provided an overview of the types of weeds that are of concern, described their ongoing planning and monitoring that will continue for a decade and informed the group about the post-fire work that had been done in other parks.

invasive knapweed was a problem prior to the fire in the area near Wade Road where the old homestead was located, and now, post fire, the weeds are gaining the upper hand. Given that this area is also where the newly built modern version of a traditional Secwepemc winter home survived the fire, it was a priority for treatment. This spring CSISS used herbicides and mechanical treatments in a mostly unsuccessful attempt to eradicate the knapweed and bull thistle here and along the trails and in the parking area.

The major feature in Tsútswecw Park is of course the sockeye salmon that at one time returned in large numbers to spawn every October. The major run that occurs every four years, peaked in 2010 with over 3,800,000 fish and has been declining steadily ever since then, with just 345,000 in 2022. If the decline continues at this rate, the Adams River sockeye could possibly become nearly extinct within a decade. Sockeye numbers have been decreasing due to overfishing, pests and diseases from fish farms, competition from Alaskan hatchery fish and the rapidly warming ocean. Another concern is the potential threat of a landslide in the heavily burned Nikwikwaia Creek which could spread sediment downstream covering the river gravel used for spawning.

2024 is the second year in the cycle, which typically has the lowest return. Since 1940, the largest number of spawners that returned in the second year of the cycle was in 1973 when there were approximately 20,000 fish, while since 2014, the numbers have been negligible. Trout fishermen have reported seeing a few dozen sockeye at the mouth of the river, near the old spawning channel and above the highway bridge, but only chinook salmon can be spotted near the parking lot.

Viewing opportunities are also limited, as the river has shifted course and there is no longer access to the island after the bridge burned. Fortunately, the two trails between the parking lot and the mouth still make for an enjoyable hiking or biking route, especially during the colourful autumn season.

POSTSCRIPT

As part of the research effort to write this article, I spoke briefly with the area park ranger who began to explain the efforts underway to re-open the park. After realizing that the current government policy does not permit staff to speak to reporters, he explained I would need to pose my questions to the media spokesperson. I was able to speak a Ministry of Environment media person in Victoria, however he was in the dark on the issue and only realized where the park was when I told him it original name, Roderick Haig-Brown Provincial Park. Thus, I had to write this article with what little information I had gleaned from the park ranger. I did get a copy of the map above that shows how most the park burned and is now closed.

When we ventured into the closed area, we met a local fisherman who explained that the closure is not enforced, as he has encountered wardens in the past who simply avoided eye contact and made no effort to fine him for being in the closed area The main reason for the closure is to make sure that BC Parks is not liable in case someone is injured. The chance of getting hit by a falling tree is very remote, except in a windstorm. Without branches and needles, the burnt sticks remain stable for decades until the roots begin to rot.

It is unfortunate that BC Parks will never salvage log and replant trees in burnt areas of parks, where wildfires are not allowed to be put out, but prefers to let nature take its course, however long that takes. The problem of course is that nature is no longer what it was prior to the escalating climate chaos and now extreme weather plays havoc with the natural recovery process. As more and more parks in the province burn, the economic impacts will worsen and our province will no longer deserve its slogan as “Supernatural BC,” but rather it will be more like “toasted, weed-infested, eroded grim BC.” Cleary, new strategies are needed to both adapt and survive as the climate heats up and to restore what has been damaged.