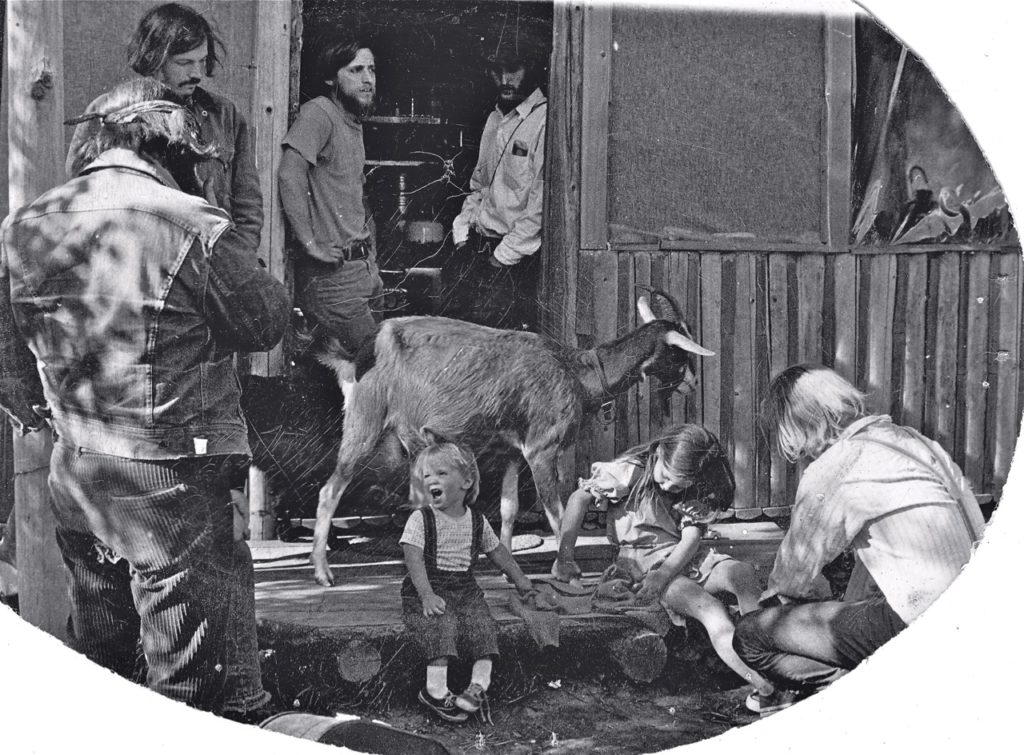

photo by Jim Cooperman

Terry Allan Simmons is known for many of his achievements, including organizing the British Columbia chapter of the Sierra Club, helping to organize the “Don’t Make a Wave” group, which was the beginning of Greenpeace and serving as a founding member of the B.C. Forest History Association. Prior to beginning his career as a lawyer, he earned his PhD at the University of Minnesota in cultural geography, where he wrote a thesis in 1979 entitled But We Must Cultivate Our Garden: Twentieth Century Pioneering in Rural British Columbia.

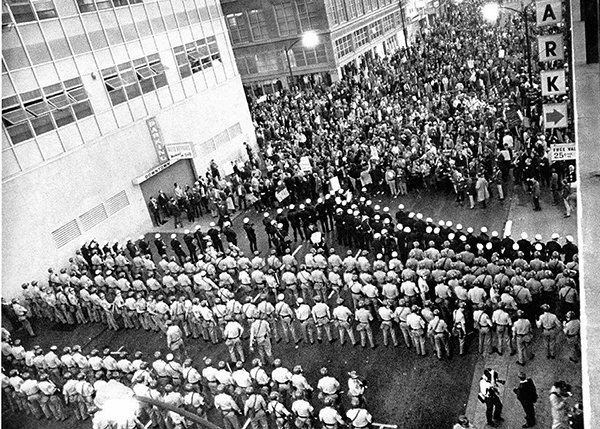

During his thesis research phase, in addition to reviewing all pertinent literature on the topic, Simmons visited communities throughout North America, including many in British Columbia and he attended 12 Coalition of Intentional Cooperative Communities meetings. In his thesis, he described the back-to-the-land movement as mostly unorganized, amorphous and a diverse group that included all ages of people from a wide variety of backgrounds, who shared a wide-range of political view and that primarily settled on marginal, low-cost land.

According to Simons, the number of people in B.C. who could be identified as back-to-the-landers was estimated to be at the minimum 15,000, which included both individual family groups and intentional communities. Essentially, the movement was a reversal of the 20th century migration trend that resulted in a mass exodus of rural people moving to the cities and represented a rejection of urbanism in favour of a healthier lifestyle more in tune with nature.

What is perhaps most significant about Simmons’ study is the discussion of the reasons why people chose to move to the country. While in the 1970s people were just beginning to become aware of the environmental problems that plague us today, they were indeed concerned about politics and the threat of nuclear war. Simmons described the movement as an “optimistic response to a pessimistic interpretation of modern life,” in which the participants seek to escape the “pathos of modern life to create viable alternatives to it.”

For those of us who were part of the back-to-the-land movement 40-50 years ago, the decisions we made then still resonate today. We chose an alternative lifestyle as a way to cope with the social decay of the times with the goal of developing a better world for the future. Now the future is here, and the problems have only intensified. Country living, while still more desirable than life in crowded, polluted cities, is no longer a haven, especially during the forest fire season.

To date, I have provided stories about a number of Shuswap’s intentional communities and for many of the others the complete story may never be told. For example, close to Cherryville there was a community established in the mid-1970s called Dandelion Landslide that was dedicated to art. Living there were a number of graduates from the Kootenay School of Art, who made pottery and sculpture, as well as painted.

In the early 1970s, former Okanagan college instructor Tom Marshall was living in the U.S. and eager to move to Canada. He read an ad in the Mother Earth News for the Fantasy Farm community in Grindrod that was looking for members and he headed there in 1974. It was owned by a lawyer who was eager to share the property with young idealists looking for a better life. It did not take long for the experiment to fail and Tom moved away within a year.

When the Hailos Community in Bear Valley faded, a splinter group that included Ira Zbarsky purchased a farm on Branchflower road in Silver Creek where they formed a Co-op. They lived together in an 11-bedroom house and grew a large vegetable garden. Unfortunately, their home was destroyed by fire and with the insurance money, they moved to a property they purchased above Blind Bay. In addition to organizing a short-lived intentional community, Ira was a local activist who helped set up other co-ops, started the first farmer’s market and opposed development without success.

POSTSCRIPT